Authors Abbey Pangilinan, Ica Fernandez, Nastassja Quijano and Cedrik Forbes discuss the challenges of data, government relations, ethics and public engagement in their research on the Philippine drug war

_______________________________________________

Research in the midst of ongoing violence and shrinking democratic space presents a range of ethical and methodological challenges that tend to dissuade most institutional researchers, at a time when critical and rigorous engagement is needed most. We speak of our experiences as local independent researchers examining the effects of the so-called Philippine Drug War on urban poor families, building from more than two years of fieldwork in various communities in Metro Manila.

What began in 2016 as a MSc dissertation at the LSE became an informal alliance of development professionals engaging the issue outside the protection of academic or policy institutions, in their spare time. It has now evolved into a multi-strand collaborative research project with an informal network of community leaders, artists, photographers, and musicians to disseminate research findings in a manner accessible and useful to the urban poor affected by the drug war.

But to get to this point, we had to overcome four major methodological challenges: obtaining reliable data, working with government officials and other researchers, ensuring an ethical process of engagement with affected poor communities, while attempting to do so in a non-extractive and collaborative manner.

Challenge One: Data

A major challenge for robust analysis lies in the numbers. The Philippine National Police (PNP) has admitted to killing 5,526 drug personalities in anti-drug operations as of July 2019, while the last reported count of deaths under investigation (DUI) was at 23,327 cases in March 2019. Although the Philippine Government has released a unified portal on the topic, RealNumbers.ph, various instrumentalities such as the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency and even the President of the Philippines himself has tended to report different figures, all of which are aggregates that are next-to-impossible to verify or analyse. The PNP withdrew from the Freedom of Information (FOI) portal in March 2017.

As such, the team had to compile its own working dataset of drug-related killings (DRK) using information provided by community sources. Data validation was carried out for the DRK database through validation of entries with online sources, specifically media reports. Obvious resource and time limitations led the team to delimit data collection to Metro Manila, and only to the first year of the drug war under Duterte, from April 2016 to December 2017. Portions of the dataset that had consent from respondents were shared with a composite team at the Human Rights Data Analysis Group (HRDAG) and Columbia University for a statistical analysis of twenty-three (23) different datasets. This led Ball, et al (2019) to note that all official and supplementary databases of DRKs are grossly understated, and that a more accurate tally is approximately 2.94 times greater than existing police reports.

Challenge Two: Constructive Engagement with Government

A constant argument by non-government stakeholders is that the ‘Philippine War on Drugs’ is a misnomer—that it is actually a war on the poor. Our work aimed to examine this popular assertion by focusing on a specific and the most officially-legible subset of the poor: the beneficiaries of the Philippine conditional cash transfer scheme, the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program. While CCT beneficiaries are only a fragment of the poor, they are the most ‘legible’ to policy interventions given that their identities are encoded in two national databases: the National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction (NHTS-PR) or Listahanan, and the CCT beneficiary database. As of 2019, government investment in the CCT totals approximately 500 billion pesos (10 billion US dollars using October 2019 conversion rates) including loans from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank.

An October 2019 release from the research project finds that at least 333 victims out of 1,827 identifiable DRK cases in Metro Manila from June 2016 to December 2017 were CCT beneficiaries. This is equivalent to anywhere from 1,365 to 1,865 affected household members, including at least two children per family. At least 12 cases involved multiple killings within the same family drug-related killings negatively affect CCT beneficiaries and their families.

Working with government data presents the challenge of constructive engagement with national, regional, and local government authorities. In a political environment where any form of critical analysis is seen as negative, the project sought to engage career bureaucrats by advocating for policy change by producing hard data that they can use. This was not possible without the buy-in of dedicated social workers and development managers in the Philippine bureaucracy.

Once formal permissions were obtained, briefings provided to DSWD officials throughout the research process, ensuring that families were quietly referred to the system for case management. All of this was conducted in an environment of political instability, where the primary client ministry underwent at least four changes in leadership.

Positionality plays a major role in this process, as all researchers were former government workers, two of whom were officials of the DSWD and so are intimately familiar with the data and systems involved. To ensure methodological rigour, the team held periodic briefings with fellow researchers and opened up an unofficial peer review process with Filipino and foreign academics.

Challenge Three: Ethical Engagement with Affected Communities

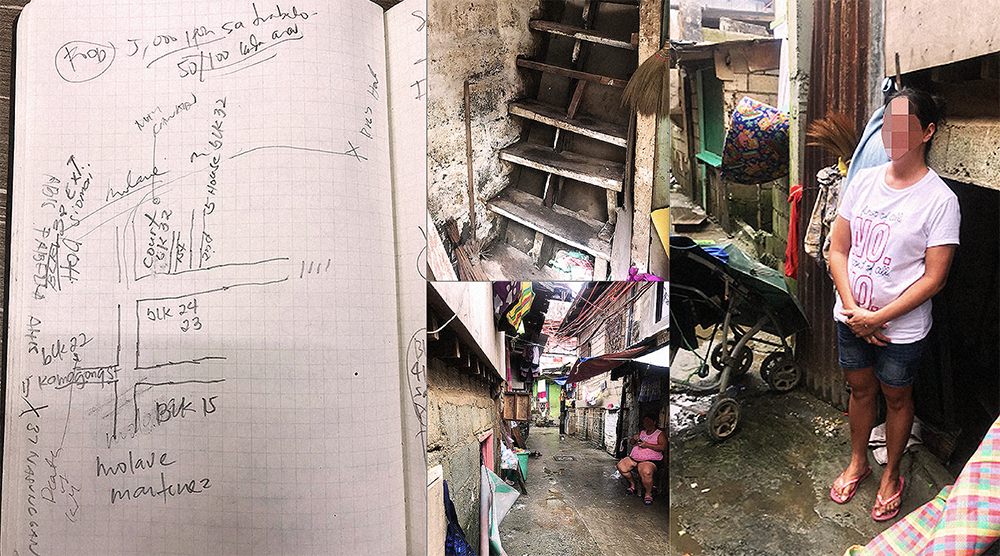

While the early research process involved database building, cleaning, and name-matching, all findings had to be validated with extensive community interviews and consultations. The primary consideration was how to conduct research in a way that is ethical and assures the safety of all parties, particularly community partners and respondents.

While field access was established through long-standing relationships between the researchers (as community facilitators and organisers) and partner organisations, protocols were put in place to ensure the confidentiality of the information provided and the identities of the families involved.

Data collection took a narrative-driven approach that allowed respondents to tell their stories, drawing out their sentiments on their situation after a drug-related killing. The research found that most victims were breadwinners, leading to a decrease in household income. The reduced available income, as well as the social stigma of having a drug-related death in the family, frequently results in children covered by the CCT to drop out of school. Widowed parents often find new partners, leaving the children with aging paternal grandmothers. The direct effects of these killings, compounded with disasters and other socio-economic shocks, traumatise CCT families, erode social cohesion, and push them further into poverty

Great care was taken by the team to avoid retraumatisation. Respondents who may need psychosocial support were identified and then linked with service providers for counseling and therapy. Given that we worked with the poorest of the poor, respondents were provided with meals and food tokens to cover any loss of income in cases when the respondent had to absent themselves from work to be interviewed.

Although traditional research protocols stress that there should be clear boundaries between the researcher and the researched, we found it difficult to simply walk away after interviewing the respondents. On a whim, we got together with some musician friends and began to raise funds through hip-hop and punk gigs in bars and community spaces in raising awareness as well as money to support families affected. The funds raised were used to provide interventions for the respondents and their family, such as the provision of rice, livelihood support, and psychosocial counseling.

Challenge Four: Public Engagement

The fundraising gigs opened up opportunities for collaboration on raising public awareness and providing interventions. How can we generate work with immediate impact, and which would not be extractive vis-à-vis the local communities that constitute our partners and ‘subjects’?

Clamour for more information from community partners and young gig-goers alike led the team to search for alternatives to peer-reviewed journal articles, which are slow both to produce and publish. Language is also a major issue, given the dominance of the English language in academic publications. To ensure maximum impact, we needed to produce research in local vernaculars, in the language of the street. The group eventually expanded to the SANDATA project, an alliance of researchers and artists wanting to harness the power of evidence and collaboration across different fields in beginning to understand, resist and respond to the ongoing Philippine Drug War.

A full hip-hop concept album on the Philippine War on Drugs, Kolateral (English translations and partial policy annotations can be found here) has since gained some traction, leading to talks at universities across the Philippines, as well as sessions at the University of Cambridge, Columbia University, UC Berkeley, and Harvard Kennedy School.

An illustrated article was released on the role of local government officials in anti-narcotics operations was also converted into a podcast. A second article illustrated by street artists Gerilya on the conditional cash transfer beneficiary-families has been recently released with the support of the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism’s Story Project.

Ultimately, all of these action research efforts are meant to build the evidence and popular pressure for support packages to mitigate untoward effects on affected families.

While the risks are real, we find that the advantages of building evidence and bridges of collaboration across disciplines outweigh the costs. As non-affiliated researchers (or the so-called ‘development precariat’) working on infrastructure, social protection, land, peacebuilding and security issues with the Philippine government, who are moreover only doing this in our spare time, any crackdown may have a deleterious impact on our professional lives. That said, the generational wages of silence and inaction are higher. With visibility as our primary protection, we find that it is an ethical imperative to use whatever research skills and resources are available to shed light on issues affecting our neighbours, and to continue building evidence for policy measures to address and mitigate suffering.

—