As vaccines roll out and restrictions are lifted, public debate is turning to the economic recovery from COVID-19 and the deepest annual downturn for 300 years that came in its wake. But viewing the years ahead simply as the post-pandemic period is far too limited a frame, say the authors of the Economy 2020 Inquiry. Instead, the 2020s look set to be the decisive decade during which the UK will need to renew its approach to achieving economic success.

The economic shock caused by COVID-19 and the associated containment measures resulted in the largest annual contraction in GDP in three centuries. Unprecedented fiscal support sustained household incomes and attenuated the rise in unemployment and business insolvencies. And a successful vaccination rollout means a recovery is now underway and forecast to continue, even if the uneven global rollout of vaccinations and related risk of mutations pose risks.

Choices countries make do matter for their relative economic strengths

As with any major recession, the pandemic will drive change for years to come. But it will do so in unique ways. All downturns have lasting impacts from the direct effects on people (e.g. unemployment) and firms (e.g. debt). This crisis will be no exception. The associated rise in unemployment will last for several years, while the highly unequal impact of the crisis will have a lasting legacy. That will include damaged labour market outcomes for low earners and the young, with higher savings for the rich and more debt for poorer households. That legacy will need to be addressed during the 2020s.

Beyond these direct impacts, the COVID-19 downturn was brought about by huge behavioural change (reductions in mobility and face-to-face interactions, partly voluntary and partly legislated) required to control the virus. It is the continuation of some of those behavioural shifts that may be the driver of lasting economic change after this crisis. The two most obvious are the growth of online retail and home working. Online retail has skyrocketed since the onset of the pandemic: from 19 per cent of total retail sales in February 2020 to 36 per cent in January 2021. Most tellingly, only half of the 14-percentage point increase during the first lockdown was reversed during the opening up of Summer 2020.

This turbo-charging of a longterm trend will have implications for those employed in retail, the majority of whom are women. Only 5 per cent of those in employment worked ‘mainly from home’ in late-2019, but in the depths of the first and third lockdowns (April 2020 and February 2021) almost half of those who were working reported doing so from home. Working from home is particularly prevalent among higher-paid and higher-educated workers. At least some of the pandemic-induced increase in home working is likely to remain once social distancing restrictions are lifted.

A durable shift towards more home working and online retail would drive major changes for firms, workers and places. As ever, there would be winners and losers. A move to greater home working may be a welcome lifestyle change for some professionals and could spread well-paid jobs geographically, aiding efforts to level up less affluent parts of the UK. But for those, generally lower earners, who provide local goods and services, it could mean significant economic disruption as they are forced to find new jobs in new places. Similarly, some consumers will choose to shop on the internet more often, but the labour and capital employed in the retail sector will be forced to move and be redeployed.

Even a relatively small change in the nature of retail or location of office work could have profound consequences for the economic geography of the UK. The pace as well as the extent of change matters here. A swifter move to online shopping means a faster decline for high street retail, making it harder for some town centres to successfully adjust. But at the moment there is huge uncertainty about the degree to which these shifts will persist. Even in the very unlikely situation where none do so, though, the pandemic should still make us reassess our economic strategy.

The UK now faces a decade of change, as the aftermath of COVID-19 comes together with other far-reaching shifts. Alongside Brexit and the Net Zero transition, two ‘new’ shocks for the 2020s, the economy and policy makers will also have to grapple with continued technological change and population ageing, which is set to accelerate in the 2020s. The direct fall-out of these must be managed well, with those who lose out supported through the process. These shocks will also reshape the context within which a renewed economic strategy must be built. This matters for far more than economics. Slow growth, high inequality and badly-handled economic disruption undermine wellbeing, intensify social divisions and create political problems all with enduring effects.

What is at stake

It is easy to paint a picture in which the economy ‘levels down’ over the 2020s, as the young and low paid suffer from the lasting impact of the pandemic, investment levels remain suppressed due to uncertainty, and opportunities to lead in new low-carbon industries are missed due to the costs of adjustment. The problems of the past may be ignored, and the challenges of the future only addressed haphazardly. Rather than redesign the country’s economic model, we may choose to muddle through. That choice would leave the UK highly exposed to the risk of a prolonged era of relative decline.

Germany and France are about 15 per cent more productive than the UK. Halving this gap would mean a boost to household incomes of 8 per cent or £2,500 per household per year

It is also possible, however, that the scale of change facing the country acts as an impetus for major reform. That could see a renewed vision for how we successfully compete in high value-added tradable sectors, while recognising the role of policy in ensuring non-tradable sectors provide widespread good employment in every community. Our cross-party consensus on Net Zero could mean we are better able to seize the opportunities the transition may bring. We might broaden our lens to consider these changes in the round rather than in isolation – enabling us to go beyond crafting individual economic policies and instead rebuild the UK’s economic strategy. The end point would be a more prosperous, fairer, greener and healthier nation.

Choices countries make do matter for their relative economic strengths. As of 2019, productivity was about 15 per cent lower in the UK than the average across France, Germany and the USA. It was not always this way. From the industrial revolution until the aftermath of the Second World War, UK productivity exceeded the average of this group. The UK then fell behind, but the period between approximately 1990 and the global financial crisis was one in which the UK made up some of the ground that it had previously lost. But that process of convergence has once again become one of divergence in recent years.

The coming decade could be one of catch-up or continued divergence. History shows us that the performance of different countries has been markedly different in decades past, as some have pulled ahead while others experience relative decline. Take the example of Italy. In 2000, Italy’s GDP per capita was 9 per cent higher than in the UK, but by 2019 it had fallen 12 per cent below the UK. Over this 19-year period Italian GDP has essentially flatlined, largely as a result of a very poor 2010s. A decade of underperformance can transform a country’s economic place in the world, and the living standards of its population. Italy’s GDP per capita is now on a par with Spain’s, having been 22 per cent higher in 2000.

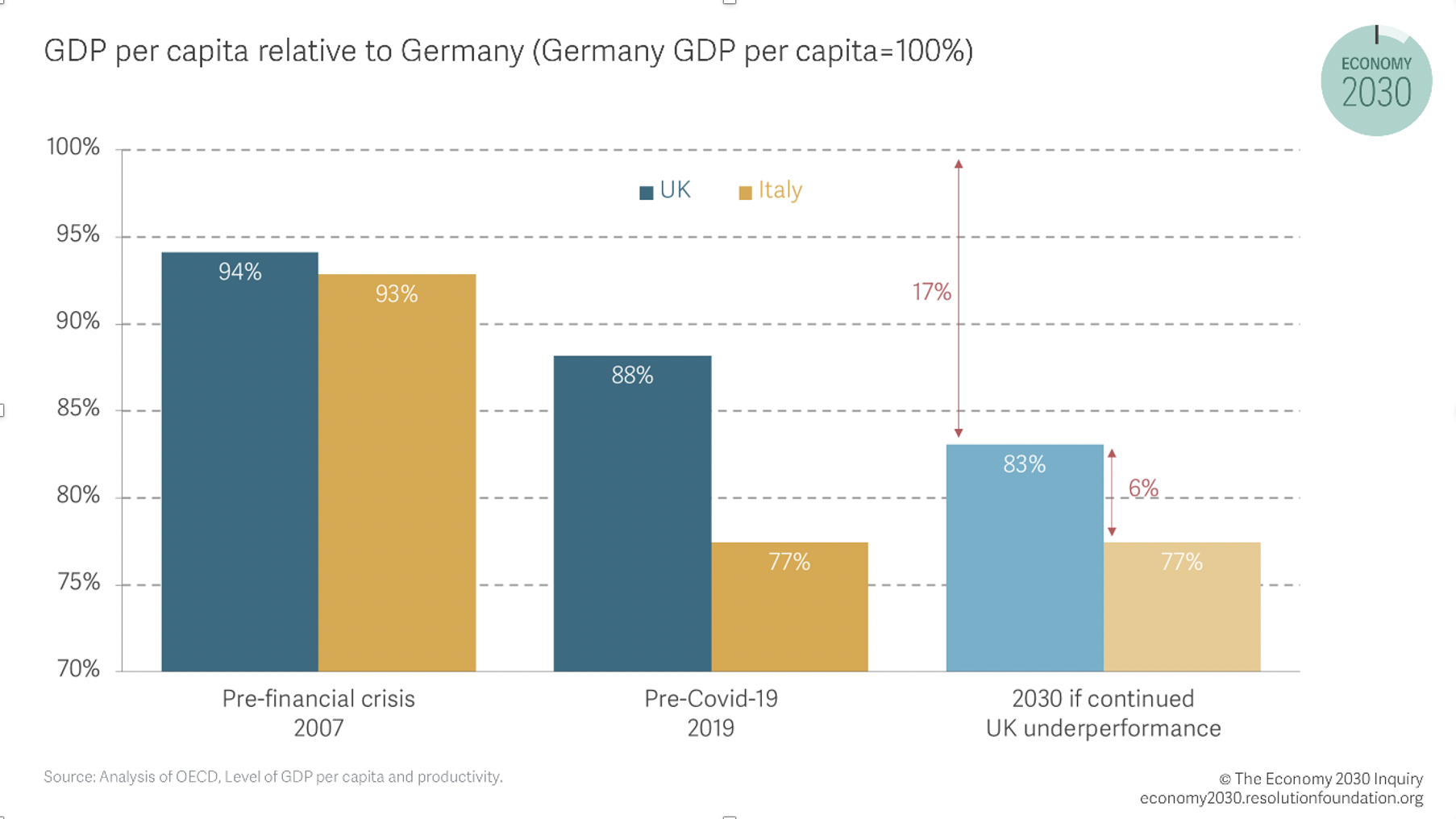

How does the UK’s international performance compare? We can use Germany as a reasonable benchmark: it is a similarly-sized European country and – until recently – operated in the same market as the UK. In 2007, GDP per capita in Germany and the UK were similar, with the UK just 6 per cent smaller. However, a large financial crisis and a slower recovery from it mean that the UK has underperformed in the past decade. By 2019, the UK’s GDP per capita was 12 per cent smaller than the level in Germany. As Figure 1 shows, Italy underperformed to a much greater extent with GDP per capita falling from 7 per cent below Germany to 23 per cent below in the space of 12 years.

Figure 1: Continued UK underperformance may leave us with an economy much closer in size to that of Italy than Germany

If the UK’s pace of underperformance relative to Germany were to continue at the same pace in the 2020s as in the 12 years to 2019, then the country will end this decisive decade with GDP per capita much closer to that of Italy than Germany: 17 per cent lower than Germany, and just 6 per cent higher (relative to the level of GDP per capita in Germany) than Italy. This is, of course, a thought experiment, relying on the assumption the gap between Germany and Italy remains constant throughout the 2020s. But it highlights a broader truth that fatalism about the relative economic performance of any country is misguided – and that big change to the UK’s relative prosperity could take place.

Just as this decade could see the gap grow between the UK and countries like Germany, it could also be a period of catch-up for the UK, with relatively strong productivity and income growth. Germany and France are about 15 per cent more productive than the UK. Halving this gap would mean a boost to household incomes of 8 per cent or £2,500 per household per year. Within these two broad scenarios, a huge range of paths for other essential outcomes is possible. The UK’s relatively high employment level, which helps mitigate the impact of lower productivity on household incomes, could rise further or fall back to historical or international norms. Inequality could rise or fall, irrespective of what happens to average incomes, but with important consequences for living standards, especially of the poor. Meanwhile, growth could be achieved in the short term, but in a manner which is incompatible with swift progress on decarbonisation.

So the real danger of failing to reset the UK’s economic strategy for this era of change goes far beyond a financial risk, important though that is. It concerns the sort of the country we will be. The last decade, here and around the world, has taught us the social and political risks of stagnant incomes, especially when twinned with high inequality. If we fail the test of this decade, then we will enter the 2030s diminished and divided. The potential prize, as well as the obvious peril, of the decade ahead is clear. One way or another, whether by omission or commission, the 2020s will be a crunch decade that will determine the UK’s trajectory into the mid-21st century.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It is an edited extract from The UK’s Decisive Decade: the launch report for The Economy 2030 Inquiry.

The Economy 2030 report is written by Torsten Bell, Swati Dhingra, Stephen Machin, Charlie McCurdy, Henry Overman, Gregory Thwaites, Daniel Tomlinson and Anna Valero.