Patrick Holden (University of Plymouth) looks at whether regional institutions like the EU, Mercosur and ASEAN have risen to the challenge of the pandemic. Should they – could they – have done more?

The current crisis might have seemed an ideal time for regional integration institutions to act. Given the spatial dimension of the virus and its economic impact, cooperation between neighbouring states is more important than ever, and regional institutions are made for this purpose. They are ideally suited to taking a holistic approach, as they combine trade agreements with different forms of socio-economic and political cooperation. Academics have often placed great hopes in regional-level cooperation, which Katzenstein argues has a ‘Goldilocks’ quality; it transcends the limitations of the nation state, but is more practical and grounded than global multilateralism and hyper-globalisation. Yet when the crisis hit, as outlined in my recent study for the United Nations University, the trade response – outside of Europe at least – was overwhelmingly state-led.

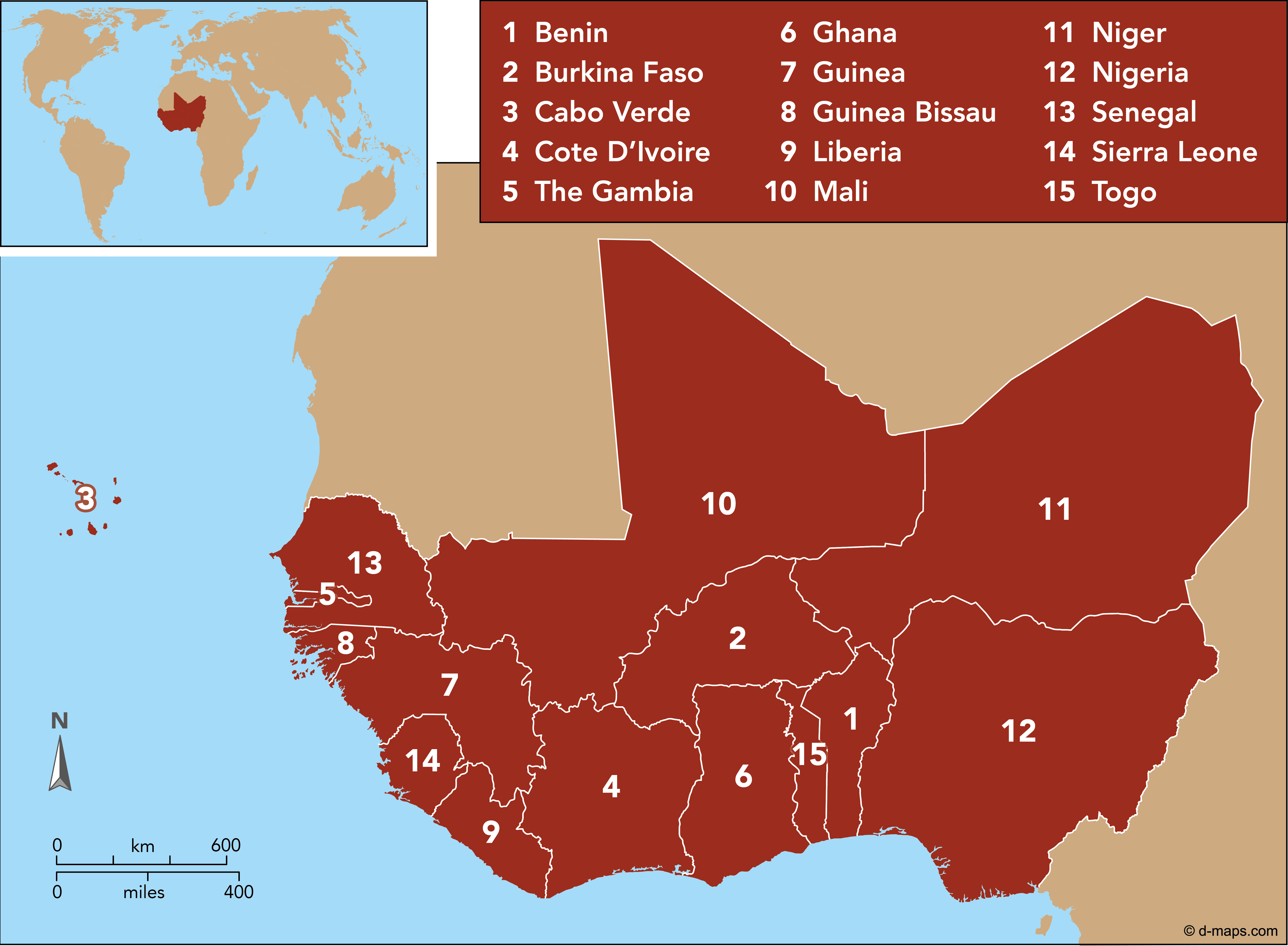

By regional integration here we do not mean simply regional trade agreements such as the US-Canada-Mexico agreement of 2020. Regional integration institutions refers to entities with a broader remit which, at least in theory, reconfigure the sovereignty of members via binding rules. Of course the best known example is the EU, but there are a range of other institutions, including the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Common Market of the South (Mercosur) and the East African Community (EAC). These institutions are generally poorly understood, sometimes overhyped – popping up in the business media as the ‘South American EU’, or the ‘West African EU’, and so forth – but more often ignored.

All of these organisations are distinct, rooted in their own regional politics, and one must beware of holding them to some inappropriate ‘standard’ of integration. Nevertheless most of these arrangements include customs unions (ASEAN does not, though it has internal free trade agreements) as well as strong aspirations for economic cooperation and unity in general, so it is worth evaluating how they responded to the crisis. The WTO and International Trade Centre databases of trade actions provide sources for monitoring what happened during the initial stage of the crisis.

For obvious reasons, the pandemic has had a massive, negative impact on trade. However, if we look at the actual trade policy measures taken by states, we see that apart from export restrictions on scarce medical/health related products, many of these were actually liberalising (facilitating the import of said products). In the first five months of 2020, 285 measures were noted by the International Trade Centre: 151 were restrictive, but 134 were liberalising.

The role of regional institutions (outside of Europe) in these trade measures was not prominent. In social science terms their ‘agency’ was not strong, in that the concrete actions were generally taken by their individual member states (and applied to fellow regional member states as well as the outside world), not the region as a unit. Figure 1 shows the list of temporary measures taken by the Mercosur member states in the first five months. Mercosur is regarded as having had a particularly bad crisis, as it came on top of tensions between Jair Bolsonaro’s Brazil and its neighbours (particularly over free trade, as Bolsonaro has a bullish approach to free trade while Argentina is much more cautious). Discussions on developing a common policy on imports of medical equipment did not develop, and member states took a range of bilateral actions on the issue.

Figure 1: Mercosur: trade measures from 1 February to 31 May 2020

| Country | Liberalising measures | Restrictive measures |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 5: including tariff reductions, suspension of anti-dumping measures and VAT waivers for health related products. | 1: export licensing for medical ventilators |

| Brazil | 4: including tariff reductions, suspension of import licensing requirements and other control measures, suspension of anti-dumping measures for health-related products. | 2: export prohibition on some medical products and export permits required for others. |

| Paraguay | 2: changes in VAT for some health-related products, tariff reduction for others | 1: export licensing requirement for PPE |

| Uruguay | 1: tariff elimination for some health-related products | 0 |

ASEAN has fewer pretensions to being an integrated region than Mercosur. Its members committed themselves to a unified approach while individually implementing their own trade controls. One of the most important of these was Vietnam’s temporary export restrictions on rice, which had important food security implications for its neighbours (as well as many other countries, it being a major supplier) but these were lifted in the summer.

The two African institutions covered displayed a similar dynamic of regional commitments but state-led actions on trade. More important than these trade policy measures was the actual effect of the pandemic on food production and supplies in particular. As elsewhere, the crisis could exacerbate ongoing tensions between neighbouring states, exemplified by the temporary trucking dispute that flared up between Kenya and Tanzania in East Africa in May.

Neither was there regional level agency in terms of significant economic interventions by regional organisations, most regional organisations lack the capacity for this (again, the exception is the EU which agreed a new €750 billion recovery fund on top of its budget). Furthermore, there is little evidence that regional institutions had significant influence on the shape of the socio-economic restrictions and interventions taken at the national level.

Does this mean that the regional institutions were effectively irrelevant, or even useless? This would go too far. The institutions did meet, and secured commitments from the leaders of their member states to maintaining vital trade and transport routes, while coordinating or at least informing each other of other activities. Institutional secretariats produced worthy coordination plans and strategies, such as this one by the East African Community. Obviously, in the trade sphere the unilateral actions taken broke these commitments, but the actual trade measures taken were modest (temporary and mostly focused on specific health related products). The regional institutions in question may have helped prevent a much more fractious response to the crisis. That is the counterfactual that we cannot know.

Looking at the broader impact of the crisis on economic globalisation the language of some of the regional institutions is significant. Talk of the regionalisation of supply chains as opposed to global supply chains abounded. For example, ASEAN declared an aim to ‘strengthen regional supply chains’. As of yet there are no concrete ideas as to how this would be achieved. Certainly the fear (or hope) that regional organisations might evolve into protectionist blocs has been unfounded: rhey are simply not unified enough to go down this path, even if there were a political will to do so.

The one institution that did demonstrate a temporary dynamic of regionalisation versus globalisation was the EU, which persuaded member states to remove export restrictions to each other partly by putting temporary controls on exports beyond the Union. These were ended on 26 May 2020, and the Commission was quick to disavow any notion of ‘fortress Europe’, aspiring instead to ‘open strategic autonomy’, which means providing economic security through diverse supply chains and smart stockpiling rather than autarchy.

Of course the COVID-19 economic crisis has only just begun, so the role of regional integration institutions could well develop. As we enter a post neoliberal world (the crisis has surely swept away the last vestiges of simplistic beliefs in a small state and the free market), the response to the crisis will necessitate more state interventions. These will inevitably affect neighbouring trade partners and thus the need for coordination, if not negotiation, will grow. The regional institutions are tailor-made to facilitate this. Similarly, the new salience of links between health and economic policy should give rise to creative interventions at the regional level: perhaps regional integration can move beyond a reliance on trade liberalisation. There may even be increased public support for practical, functional, transnational cooperation on health and environmental protection, as long as the benefits are clearly apparent.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.