What has happened to the prevalence and nature of domestic abuse during lockdown? Crime economists Ria Ivandic and Tom Kirchmaier collaborated with the Strategic Insights Unit (SIU), from the Metropolitan Police, to answer this question by analysing data from calls to the police and recorded crime in London.

Home is not a safe place for everyone. As social distancing has become the dominant policy response to suppress COVID-19, there have been unintended consequences for domestic abuse victims. We find that, though the total number of domestic abuse crimes did not increase, crimes between current partners did increase, but this increase is not visible in the total due to a corresponding decrease in crimes between ex-partners.

We base our analysis on five years of crime records and two years of calls-for-service data from London’s Metropolitan Police Service (MPS). This individual-level data allows us to provide a reliable empirical assessment of the changes in volumes of domestic abuse during the lockdown. Both data sets ran to the 14th June 2020.

Each year, the MPS receives about 2.5 million calls for service, out of which 170,000 (~7 per cent) are related to domestic abuse. In the eleven weeks from the beginning of lockdown, there were a total of around 45,000 calls to the MPS contact centres related to domestic abuse.

In 2019 out of these calls there were about 900,000 crimes, with 9,7 per cent of those being Domestic Abuse related. Since the lockdown started there were 19,155 domestic abuse offences recorded.

Calls for Service Findings

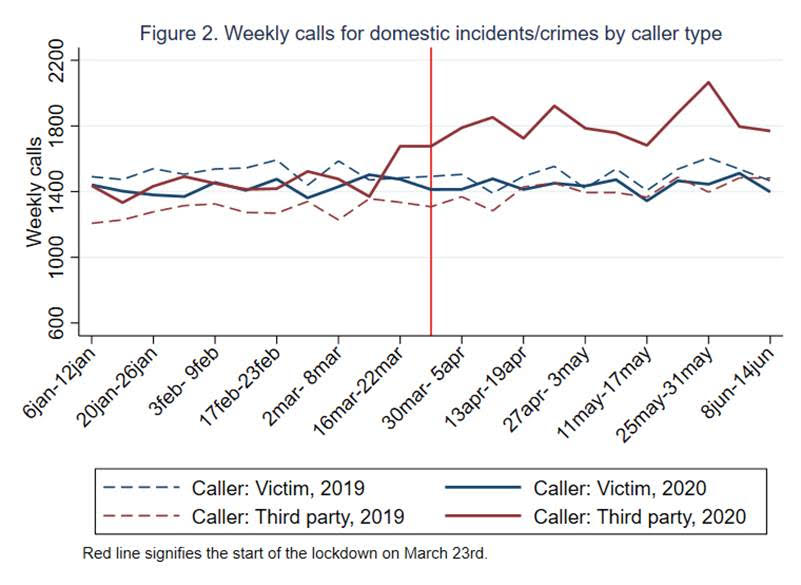

Since the lockdown domestic abuse calls to the police have increased by 11.4 per cent on average compared to the same weeks in 2019 (see above Figure 1). The increase is almost exclusively due to an increase in calls from third parties who are not directly witnessing the incident, that include neighbours or family members (see Figure 2).

As a counterfactual for what trends in 2020 would have been without the lockdown, we compare the calls in 2020 with those in the same week of 2019 (baseline). Figure 1 depicts the divergence in the trend between the two years that starts about two weeks before the official lockdown and then remains substantially higher. The difference equates to about 380 more calls per week on average as a result of the lockdown, and more than 4,592 in total.

We disaggregated the data in Figure 2 to see the differential effects by types of caller. We observe that since the week of March 16, almost all of the increase in domestic abuse calls comes from third party calls.

This increase in calls from third parties might point to an increased awareness of noise as neighbours are now at home; increased awareness of domestic abuse since public narratives in the media voiced concern for victims during the lockdown; potential under-reporting by domestic abuse victims; or a combination. To alleviate the issue of domestic abuse victims not being able to contact the police, SIU and LSE launched a targeted social media campaign to promote the Silent Solution, which allows victims to contact the police with minimal verbal communication.

Crime Findings

While the overall level of domestic abuse crimes (not calls) have remained stable when compared against the long-term trend, we observe a considerable shift in the type of abuse. While abuse by ex-partners fell by -9.4 per cent, abuse by current partners and family members increased significantly – by 8.5 per cent and 16.4 per cent – respectively since the lockdown began.

We examine whether the nature of domestic abuse has changed. We estimate this using an event study methodology using five years of weekly time series data. While the overall level of domestic crimes is roughly stable at 1,500 per week for the Greater London area, this average masks important diverging trends between current partner and ex-partner crimes, and intra-family abuse.

As discussed, current partner crimes during lockdown increase by 8.5 per cent on average, with considerable variation over the weeks; see Figure 3a. For example, in the worst week, crime was up by 18.9 per cent compared with the baseline. Similarly, family domestic abuse was up 16.4 per cent on average, to about 380 cases per week during lockdown. Over the same period, ex-partner crimes decreased by 9.4 per cent as compared to baseline (see Figure 3b).

This is an important finding, as it shows that there are groups of victims that are suffering considerably more during lockdown, groups that should be targeted by focused policies. It also highlights the opportunity to maintain the reductions in ex-partner abuse after the lockdown.

Policy Implications

The social media campaign launched by LSE and MPS to promote alternative means of reporting is showing positive engagement in terms of clicks. We propose continuing this research to investigate how best to communicate with victims. The observed shift in the type of abuse to current and intra-family abuse invites rethinking how to best identify and target households where domestic abuse might occur for the first time and finally, given that we have identified a reduction in some aspects of domestic abuse, there is an opportunity to consider how that reduction might be maintained.

Notes: The official lockdown started on 23 March, but a significant number of workers were advised to work from home, and uncertainty about the scale of the pandemic and its economic implications spread over the news the week earlier. The Strategic Insight Unit is led by Simon Ruda. Inspector Ben Linton led this work for the SIU.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE. It will be featured in the forthcoming issue of CentrePiece – the magazine of the Centre for Economic Performance. Image: Gala Pont (http://gala-pont.com).