People struggle to know whether they should prioritise public health or the economy in the COVID-19 crisis. Emanuele Ferragina and Emily Helmeid (Sciences Po) analyse the results of a French survey which reveals that, faced with the prospect of economic catastrophe, a majority favour ending lockdown – even though they would rather sit on the fence.

Experimenting with moral uncertainty

Are we more worried about health or the economy during the COVID-19 outbreak? The crisis is not only a public health issue, but also an event that is reshaping our worldviews. In a situation where political leaders seem unprepared, the economy is on an uncertain footing, hospitals lack space, equipment and staff, and we fear for our loved ones and ourselves, uncertainty looms large. Indeed, in spite of a 24-hour news cycle, we lack the information to understand what is really going on and, therefore, to imagine the immediate and long-term future. Every additional day in lockdown could save hundreds of lives, but at what cost to the economy? The danger of such a volatile situation is that public opinion can be easily manipulated, and this is, in effect, what our study shows in France when it comes to concerns over health and economics.

What do people say they are most worried about?

To try to understand how people view the inherent trade-off between saving human lives and rescuing the economy from complete collapse, we went straight to the source: a nationally representative sample of the French population, from which we have been collecting data since 2017. In both the beginning and middle of April, we posed a direct question to our panellists, asking them to try to make the choice by placing themselves on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means being completely concerned with the health dimension of the crisis and 10 with the economic dimension.

Uncertainty looms large

Making a direct choice between health and the economy is rather difficult to do. As a result, many of our panellists declare feeling equally worried about both of these dimensions and placing themselves squarely at the centre of our scale. But in the space of two weeks, 67% of our panellists changed their minds on this question: 41% have become increasingly concerned with the economic consequences of the crisis and 26% with the health consequences. Only one out of three respondents maintained the same view over the period.

We also investigated these concerns by income level and gender. In the most well-off households, people are increasingly worried about the economy (from 35% to 49% between the first and third weeks of April). Those in the least well-off households, by contrast, are increasingly moving to the middle of the scale (from 27% to 33% over time). The latter is counter-intuitive, as one might expect the most disadvantaged to focus primarily on the economy given that any loss in income could put their material wellbeing into jeopardy.

In looking at the difference between men and women, we see a similar pattern. Four weeks into the lockdown, 41% of men are most concerned by the economic impact of the crisis, compared to 27% of women. Women are more likely than men to have changed their stance on this issue and to place equal weight on health and the economy (34% compared to 24%).

But deep down, what are they actually most worried about ?

In the second wave of our survey in mid-April, we also submitted our panellists to an experiment designed to indirectly reveal which aspect of the crisis is truly of greatest concern to them. Panellists were randomly divided into two groups and asked to consider the issue of a partial reopening of France starting on 11 May 2020 – the date that had just been announced by President Macron. The first group was given a scenario in which the number of infected persons had not diminished as much as foreseen and asked if partial re-opening on 11 May should still occur, or if a strict lockdown should be continued. The second group was given the same scenario, in terms of health, but was also told that “experts fear that continuing with the lockdown could further aggravate the economic crisis, leading to millions of unemployed and the bankruptcy of up to 25% of all companies”.

The result of our experiment is striking. Support for partially reopening the economy on 11 May regardless of the number of active cases was at only 35% in the first group, but it jumped to 65% for those in the second group who had been warned of the damage a protracted lockdown could do to the economy. Our findings suggest that public opinion on the matter is highly susceptible to manipulation. All it took for a dramatic shift in the share of those wishing to pursue reopening regardless of the human cost was one additional piece of information from a seemingly authoritative source.

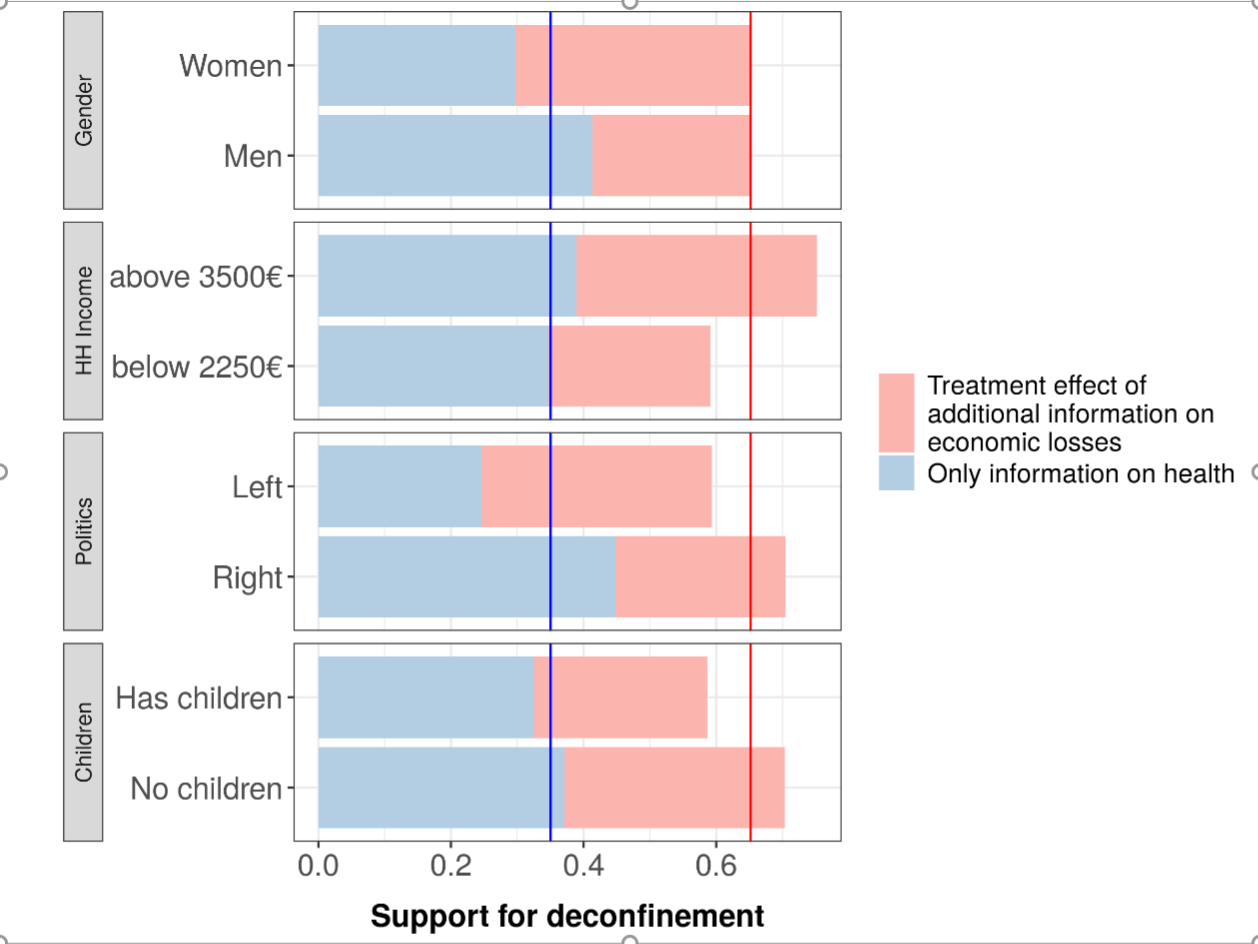

Figure 1 illustrates the result of our experiment across gender, income levels, political preferences, and households with and without children. Among the first group only 30% of women and 41% of men support partial reopening. When presented with the additional piece of information, the proportion of those in support of reopening as planned jumps more dramatically among women than it does among men, but results in equally high support among both at 65%. While the most and least well-off individuals support reopening in almost equal measure when only considering the health scenario (39% and 35%, respectively), the most well-off are much more likely to support it in view of a potential economic crisis (75% against 65%).

Politically speaking, those on the left are much less in favour of re-opening than those on the right (25% and 45%) when it comes to the first scenario. In view of imminent economic collapse, the difference of opinion shrinks somewhat but, nonetheless, remains considerable (59% support on the left and 70% on the right) . Overall, people with children seem to be most concerned about the economy, and even more so when confronted with the possibility of catastrophic unemployment levels and widespread bankruptcy.

Figure 1: Support for ending the lockdown

Source: Coping with Covid-19 – 2nd wave (CoCo-2), April 15-22 2020, ELIPSS/CDSP

N=880, 559, 665 and 908.

Reading: The vertical lines represent the support for deconfinement in the whole sample (35% and 65%, respectively). Then, for example, the blue part of the bar at the very bottom indicates the share of respondents without children that answered supporting ending the lockdown on 11 May, when told that the number of COVID-19 cases is higher than the government’s prediction. The blue and red parts jointly represent the share of respondents that expressed their support for reopening when presented with additional information on the potential economic losses when continuing the lockdown.

So what’s the main takeaway from all this?

Clearly there is no “right” answer in a time of great uncertainty. Whichever way you slice it, the choice is a trade-off that would leave many behind: maintain strict lockdown measures, and we could end up digging into a very long economic depression; open up to try to save businesses and jobs, and we might further increase an already heavy death toll. Our empirical analysis tell us that when people must explicitly choose between these two dimensions, they stay in the middle. Those who admit prioritising the economy might even receive our collective side-eye for their choice.

Revealed preferences are another matter entirely, though. While more than a third of the population support reopening even if the number of active cases remains high, two-thirds of the population support it when faced with impending economic doom. When pushed to it, people are currently of a mind to choose the economy over health. In short, our research shows that public opinion remains uncertain and that it can be easily swayed by a strong authoritative message.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, not the LSE.