The COVID-19 crisis is one of the largest economic shocks that has taken place in living memory. While current official statistics only pick up the very start of the crisis, the Bank of England has warned that unemployment is likely to exceed the heights of the global financial crisis and that GDP could plunge by 14% in 2020, marking the deepest recession for centuries. While the picture looks bleak on aggregate, Jack Blundell and Stephen Machin (LSE) seek to understand the impact on the self-employed, of whom there are now 5 million in the UK, making up 15.3% of the workforce.

As discussed in previous work (Blundell, 2019; Boeri, Giupponi, Krueger and Machin, 2020), the self-employed are an exceptionally diverse group, ranging from millionaire partners at law firms to part-time food delivery drivers. While some of the self-employed are likely to be extremely heavily hit by the crisis, for others the consequences are less clear. Live performers will have seen catastrophic declines in income, but for delivery drivers, there has likely been an uptick in demand for their services. In general, this diversity means it is difficult to assess intuitively the extent to which the self-employed have been hit by the economic fallout of COVID-19.

To provide rapid evidence on the impact of the crisis on this group, we ran a survey of 1,500 self-employed workers from 12-16 May. While this and other recent ad-hoc surveys do not replace official statistics, the speed and intensity of the current crisis has made them a necessity for informed policy debate over the next steps.

The self-employed have been hit very hard

We find that on average, the self-employed have been struck exceptionally hard by the crisis. Three-quarters of participants reported that they have had less work in April 2020 than they would usually have at that time of year. This is identical to the results of Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin and Rauh (2020) who show that workers in alternative work arrangements – which includes many of the self-employed – are more vulnerable to the crisis.

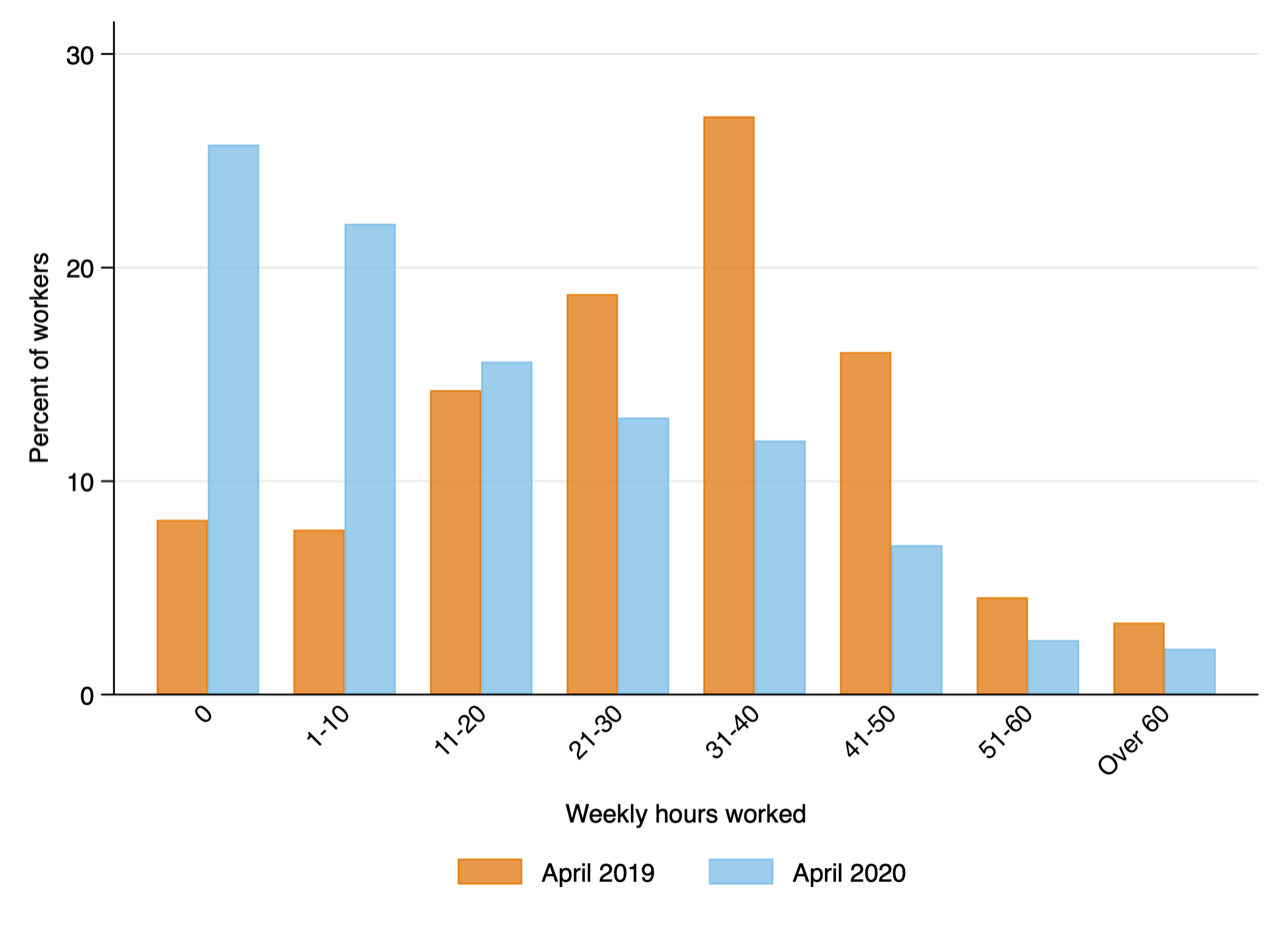

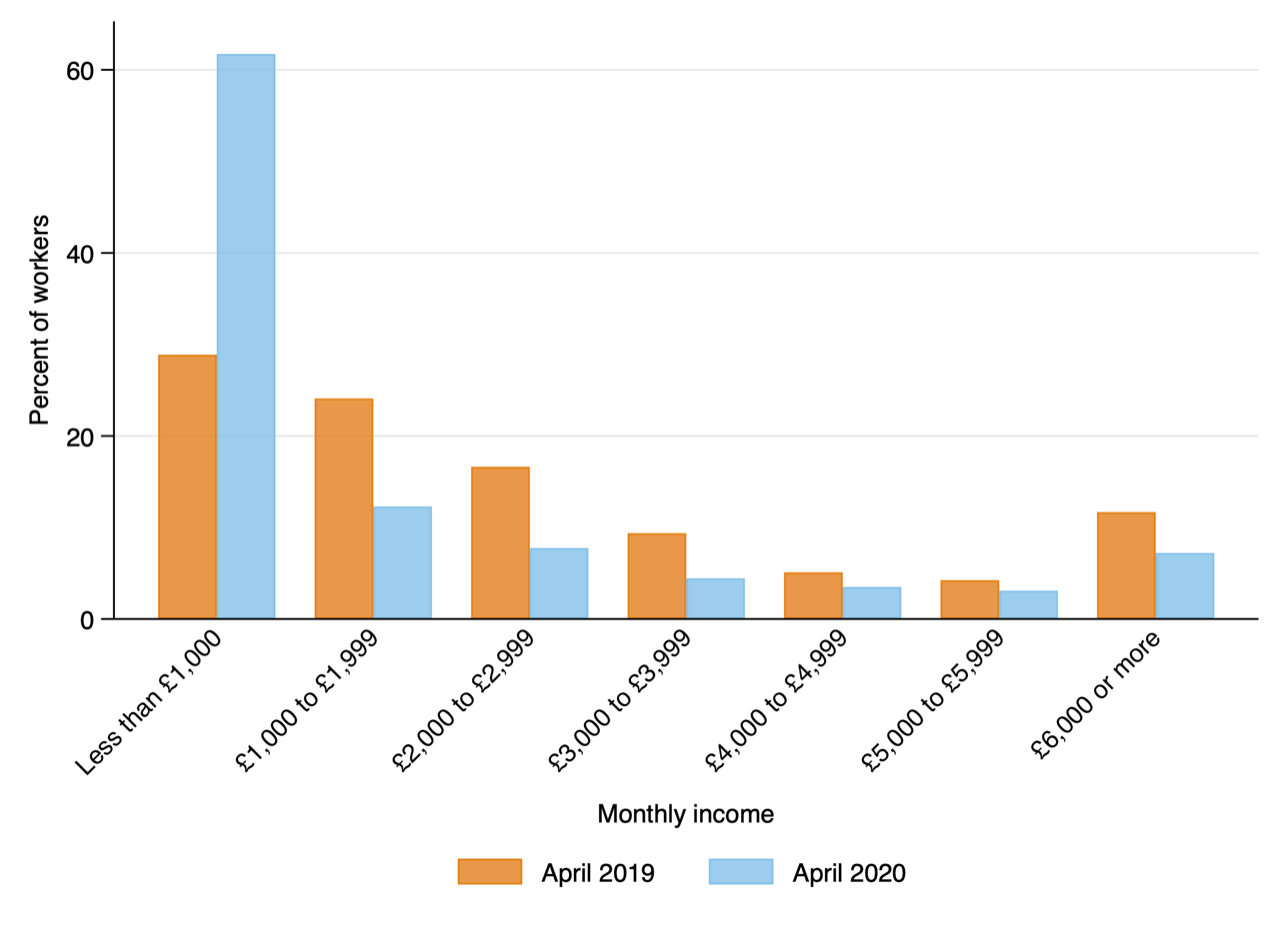

Figures 1 and 2 show that the distribution of hours and incomes have shifted down substantially. In April, the self-employed worked an average of 11-20 hours per week, down from 31-40 hours in the previous year. Over 60% of workers earned less than £1,000 this April, more than twice as many as the previous year.

Figure 1: Weekly hours in April 2019 and April 2020. Notes: Self-reported hours worked in April 2019 and April 2020. Source: LSE-CEP Survey of UK Self-employment May 2020

Figure 2: Monthly income in April 2019 and April 2020. Notes: Self-reported income from main job in April 2019 and April 2020. Source: LSE-CEP Survey of UK Self-employment May 2020

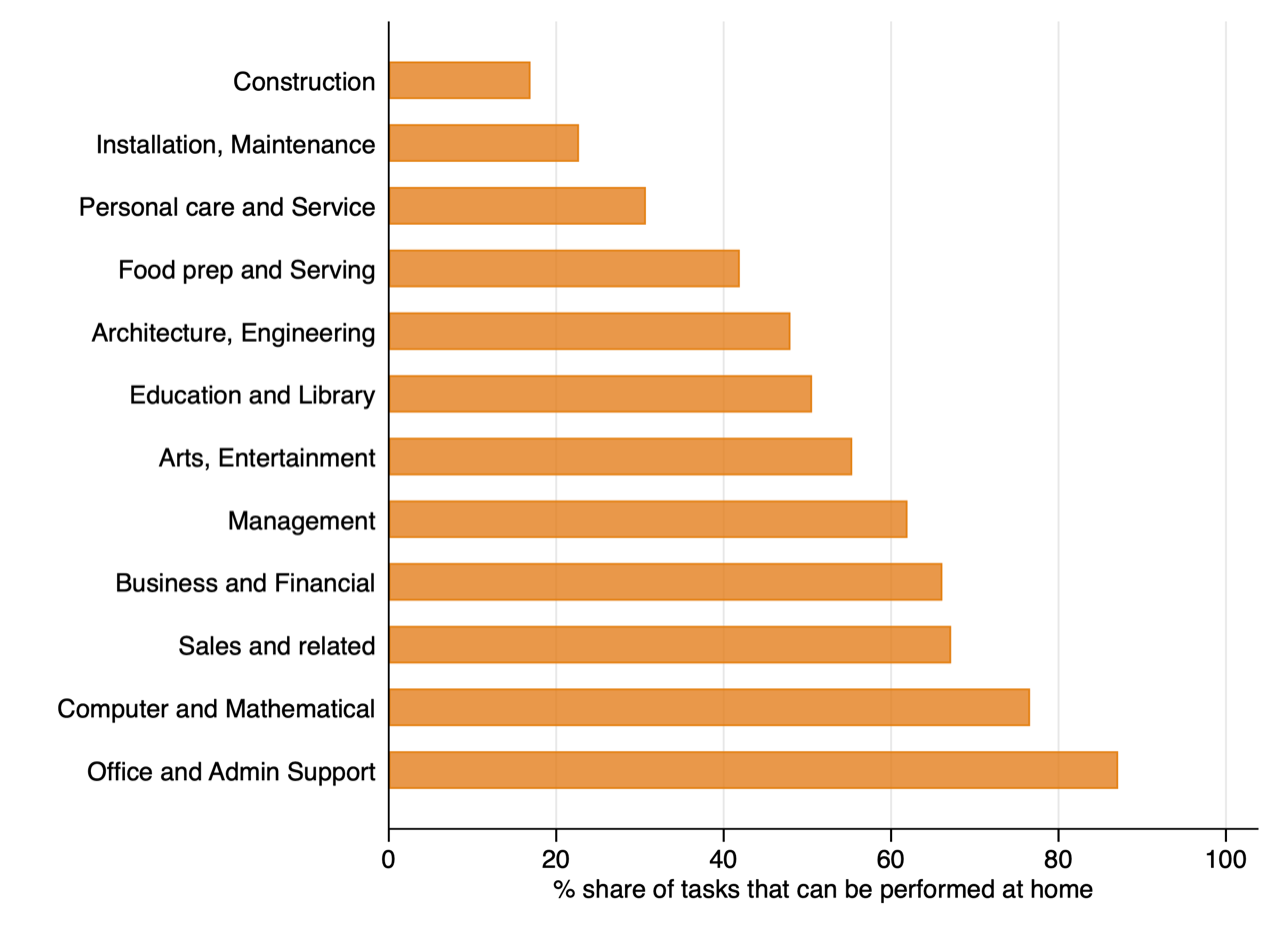

The shock is particularly large for those on lower incomes, therefore it is no surprise that many are having significant financial difficulties. We find that over a third of self-employed workers have struggled to pay for essentials since the start of the crisis. We also find the shock to be larger for older workers, and among those without employees. By far the most significant predictor of hours and income changes is the extent to which a job can be performed at home. Figure 3 shows substantial variation across occupations. Self-employed workers in office and administrative support report that 87% of their tasks can be performed at home on average, whereas workers in construction report only 17%.

Figure 3: Ability to work from home by occupation. Notes: Mean responses within self-reported occupation (US SOC) to question “To what extent can your work be done from home?” where answers are given on a sliding scale of 0 to 100. Source: LSE-CEP Survey of UK Self-employment May 2020

One distinctive feature of the current crisis is that unlike in other economic shocks, women have been shown to be particularly vulnerable. This is in part due to the sectors in which they work, and also due to asymmetric caregiving responsibilities (Hupkau and Petrongolo, 2020). For the self-employed, however, there is no noticeable gender difference on average. This is primarily driven by the fact that self-employed women are more likely to be able to work from home. Comparing men and women who are equally able to work from home, women are significantly more likely to report a reduction in work hours.

Self-employed workers feel they have put their health at risk

Underlying the current economic shock is a public health crisis. Given the lack of an employer, the inability to furlough themselves and the long wait for government support, one concern is that the self-employed may work despite health risks. Indeed, 33%, of self-employed workers have felt that their health was at risk while working. This rises to nearly four out of every five (79%) “app workers”, those people who are contracted through digital platforms, many of whom are delivery drivers. App workers report that the reason they continue working despite the risks is primarily due to the financial incentives and fear of losing work in the future.

Many workers are accessing support, but others are not sure if they are eligible

The survey was specifically timed to launch just as the Self-employment Income Support Scheme (SEISS) opened. This allows us to provide rapid evidence on how well the process is working, and on who is claiming.

The first round of SEISS provided a grant of up to £2,500 per month for three months, to those who reported losing business due to the crisis. Payments were not linked to the actual financial loss experienced, but rather were pegged to 80% of profits in previous years. On May 29th, the chancellor announced an extension of the scheme to cover another three months, with payments reduced to 70% of historical profits. As discussed in Adam, Miller and Waters (2020), the design of the scheme is such that workers who receive only a small income loss could be quite substantially better off than if the crisis had not occurred.

We find high rates of claiming from the scheme. Of those surveyed on the day of opening, 34% had already claimed. After two days of the scheme being open, that had increased to 43%. While the scheme excludes those with the highest profits, the probability of claiming from the scheme increases as personal income increases, though not as household income increases. Those with incomes between £40,000 to £49,999 a year were twice as likely (48%) to claim as those with incomes less than £10,000 (24%). Older workers and those who work from home were also less likely to claim, consistent with these groups being less likely to experience a negative shock. Somewhat worryingly, of those who had not claimed 41% were not sure whether they were eligible or not.

Most expect work to go back to normal by September, but some think it will take far longer

There is immense uncertainty over how long this shock will last, and whether it represents a more fundamental shift in the structure of work and society more broadly. We find that on average, self-employed workers believe that their work will go back to normal in September 2020. The full distribution is shown in Figure 4. Given the size of the shock, we interpret this as fairly optimistic. Most self-employed workers appear to be expecting a “v-shaped” dip in their hours, income, and work behaviour, with things back to normal relatively soon. But there are exceptions to this. A fifth think it will take until 2021 and 1 in 20 expect that their work will never return back to normal. Among those working in Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports and Media occupations, over a third (35%) believe that things will not go back to normal until after the end of 2020.

Figure 4: Expectations for the future. Notes: Responses to question “When do you expect your work to go ‘back to normal’ after the current crisis?” Source: LSE-CEP Survey of UK Self-employment May 2020

Workers would sacrifice 10% of income on average to obtain the guarantee of future income support

Alongside the offer of government support, the chancellor has indicated that the self-employed will be subject to increased tax rates in the future. This will please many who have for years called for an end to the unfairness in the current tax system (Adam and Miller, 2019), in which becoming self-employed accrues considerable tax advantages. The most likely policy shift will be an increase in national insurance contributions (NICs), bringing self-employed NICs contributions in line with those paid by conventional employees and their employers. While some argue that the difference between the self-employed and conventional employees in terms of access to the social safety net is in fact not particularly large, a key input into this debate is the extent to which the self-employed value government support.

To attempt to address the big evidence lacuna on this issue, we ran a choice experiment to identify the willingness-to-pay of self-employed workers for a now well-defined, specific type of coverage. We assessed how much (pre-tax) income workers would be prepared to sacrifice to be assured income support in the face of future pandemics and other economic shocks. The generosity of the support was specified as equal to that of the current support package. On average, self-employed workers would be prepared to sacrifice 10% of their income in exchange for such a support guarantee. Over three-quarters of self-employed workers would be prepared to sacrifice 2% of their pre-tax income in order to receive such support. In ongoing academic work (Blundell and Machin (forthcoming)), we are exploring how this varies across types of workers, and types of self-employment. In percentage terms, the solo self-employed are observed to value income support by twice as much as the self-employed with employees.

Putting it all together

The COVID-19 crisis has hit the self-employed hard. The precipitous drop in both income and hours uncovered in our survey is a sign of what has undoubtedly been an extremely challenging period for these workers and their families. Some have been hit harder than others, with lower income, older and solo self-employed workers among the most affected. For those who remain working, an alarmingly high proportion report feeling that their health is at risk. That this is particularly high among app workers whose fear of losing future work is consistent with concerns about how much flexibility digital platforms really offer their contracted workers.

The support which self-employed workers are receiving from the government cannot come too soon for many, but the analysis suggests that there is substantial uncertainty over who is eligible for this support. This only adds to the uncertainty many have over their future work prospects. Looking ahead, the results here suggest that most self-employed workers significantly value social insurance and that many are prepared to tolerate paying more in tax in exchange for the guarantee of future support.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog or LSE.

9 Comments