Buka is the administrative capital of the Autonomous Region of Bougainville. It sits close to the equator, across a sea passage from the territory’s main island, a steamy township of timber shops, government buildings, and sandy streets. During the day it has a thriving food market, a central feature of the waterfront area. Here you will find stalls piled high with local fruit, vegetables, peanuts, fresh and smoked fish, small home-made cakes and doughnuts. As in many other parts of the Pacific Island region, Buka’s market traders are usually women. They are efficient and business-like, happy to share friendly conversation as they load your arms with a heap of produce in exchange for a few Kina (the local currency), always ensuring the next potential customer is in their sights.

Bougainville is transitioning from a bloody decade of conflict in the 1990s that saw nearly 10 per cent of the territory’s population killed. In a context marked by limited development opportunities and depleted public infrastructure, women’s market work or “marketing” as it is known locally, has provided many women with an important means of economic participation. The significance of this work is recognised generally by the Pacific region’s peacebuilding and development specialists who have, in the last years, rolled out a suite of programmes to assist women market vendors.

In Bougainville, as well as in conflict affected communities in nearby Solomon Islands, programmes to upgrade market facilities to ensure that they are better geared to meet the health and security needs of women traders have been common. In some cases, these programmes have involved additional training workshops designed to build women’s skills in business and entrepreneurship as well their understanding of civics, governance and human rights.

These programmes reflect a liberal peace ethos which, alongside democratic statebuilding, places a heavy emphasis on measures to assist economic recovery. The guiding assumption is that when the economy is stable, conditions for interdependent trade are enabled contributing to increased wealth distribution and a reduced potential for the kinds of political marginalisation and violence that disrupt peace.

Boat crossing the Buka passage. Image credit: Nicole George

Women have not always been beneficiaries of these programmes, however, as the 2015 UN Women report on implementation of the WPS policy agenda clearly demonstrated. Here it was shown that economic investment directly aimed at assisting women’s economic participation constituted only 2 per cent of total investment funds to assist economic restoration in the wake of conflict. Protesting this oversight, the report went on to affirm the critical peace dividends that accrue from women’s economic activity stating that women are more likely to spend money in ways that contribute to social cohesion and recovery because their spending is focused on their own security and that of families. It was further argued that some of the most successful cases of post-conflict economic recovery owe part of their success to the ‘increased role’ undertaken by women in ‘production, trade and entrepreneurship’.

The contention that women should have access to opportunities to participate in the economic life of their communities is a just one. Yet field work experiences in Solomon Islands and Bougainville (discussed more fully here) have prompted me to question the hopeful ways in which the relationship between women’s economic participation and peaceful conflict transition is narrated in this area of conflict transition programming. While I do not dispute the idea that women are frequently marginalised from participation in the cash economy, and devote much of their slim earnings to meeting the needs of family and kin, I am concerned that the gendered logics that shape the terrain of economic exchange in these contexts are too easily downplayed. Programmes that emphasise the peace dividends of women’s economic integration can fail to address a) the extent to which women’s wealth distribution towards families and dependents is coerced and b) the potential that economically active women are also vulnerable to heightened levels of gendered harm.

While I do not dispute the idea that women are frequently marginalised from participation in the cash economy, and devote much of their slim earnings to meeting the needs of family and kin, I am concerned that the gendered logics that shape the terrain of economic exchange in these contexts are too easily downplayed.

In a recent contribution to an edited volume on new directions for Women Peace and Security research I made the case for deeper study of these risks. My thinking is informed by political geographers’ study of ‘economies of place’ as a lens on the nature of economic exchange in the Pacific Islands and elsewhere. This analysis examines how economic participation is guided by interplaying logics; liberal notions of market-based monetary transaction as well as indigenous logics that, in Pacific societies, are guided by commitments to ‘reciprocity’, ‘sharing of resources’ and the consolidation of kin and familial relationships.

The important point in this research is that ideas about wealth and well-being in indigenous societies may be influenced by interests in material accumulation in an individualised sense but this has not displaced the ongoing significance of communally-oriented, non-market relationships of exchange in these communities either.

A market trader sells food at the market in Buka. Image credit: Nicole George

The economies of place literature has shed critical light upon assumptions that communally-oriented, non-market relationships of exchange are erased or subsumed by market- based modernities. While some feminists working in this area have argued for more awareness of how these practices contribute to the standing of women, others warn against romanticisation. In Pacific Islands contexts, women may certainly achieve status and derive benefits from strengthening kinship relations through the exchange of wealth and place personal importance on this. Yet, at the same time, it is also evident that relational obligations to family and kin can be enforced in ways that see women exposed to violence and oppression (see here and here).

In their study of women’s economic participation in Bougainville, for example, Richard Eves, Genevieve Kouro, Steven Simiha and Irene Subalik noted concerning trends in the experiences of women market vendors suggesting the peace dividend from women’s ability to share their earnings has a personal cost. This study showed that in many cases male family members are accustomed to thinking of cash-based economic activity as their sole entitlement, and thus questioned the rightfulness of women’s economic participation and/or resented the fact that this equated to their loss of control over women family members.

According to the authors, this inclined men to believe that they have the right to control women’s market income and resulted in male threats or violence against women to achieve that control. This research further found that women market vendors can be subjected to greater pressure from extended kinship and family networks than men to share their wealth. This is because as small-scale vendors, women’s earnings, even if slim, are negotiated publicly and visibly while men are commonly paid as waged workers or for large-scale cash cropping and more inclined to negotiate those transactions in closed environments.

In Pacific Islands contexts, women may certainly achieve status and derive benefits from strengthening kinship relations through the exchange of wealth and place personal importance on this. Yet, relational obligations to family and kin can also be enforced in ways that see women exposed to violence and oppression.

In my own work examining women’s employment in professional settings such as government bureaucracies in Bougainville in 2014 and 2018, I recorded similar stories of working women’s exposure to gendered harms. Female departmental managers recounted their efforts to assist female employees who had been exposed to violence from male family members. In these instances husbands had become resentful of women’s earning potential and sometimes also of the fact that their work brought them into proximity with other men.

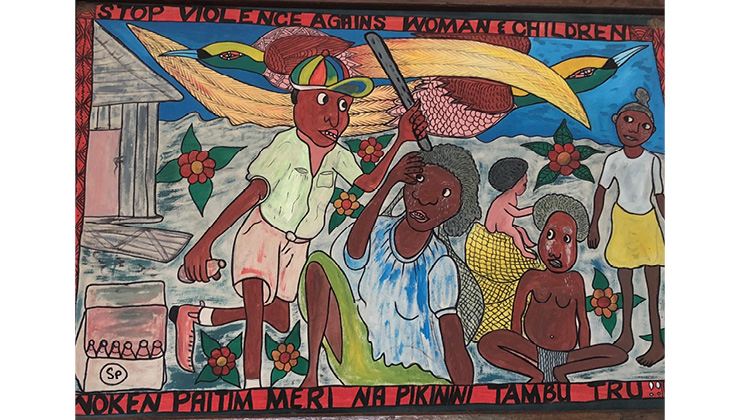

Local artwork encouraging awareness of violence against women photographed at a Catholic church dormitory in Hutjena, Bougainville. Image credit: Nicole George

Some study participants recounted harrowing stories of extreme violence perpetrated against female staff within their homes. One interlocutor explained that she had, at times, sent a departmental vehicle to more junior women officer’s homes to negotiate their safe travel to work. With a departmental car and driver in front of a female officer’s house, she found her employees were more able to safely extract themselves from the control of resentful and potentially violent male family members. Of course, such measures do little to ensure that women return to a safe home environment at the conclusion of their day’s work.

Research I conducted with family violence support services in Bougainville has also taught me that household tensions are generated not only because employment takes women outside the home, and the realm of caring, but also because this provides women with access to cash and potential autonomy. Women who make autonomous decisions about how the money they earn should be spent may be subjected to violence and this may be especially so if their spending is judged to be ‘excessive’, meaning they are accused of spending money “selfishly” on themselves rather than family or kin. Front-line crisis care workers also explained that women in professional occupations are frequently pressured by men to hand over their cash on pay days and the phenomena of women beaten because they resisted pressure to hand over ATM cards was common.

These findings show how important it is to reflect carefully on the ways that constructions of feminised ‘goodness’ and ‘duty’ provide a gendered shape to post-conflict economies. They show the need for more understanding of the prohibitions that see women who try to retain control over their earnings become censured for the their alleged selfishness and wastefulness. This is particularly so if they are seen to dispense their income in ways that ignore their obligations to kin as ‘good mothers, wives, sisters and in laws’.

These findings also highlight the problems that occur when the economy itself is treated as a gendered vacuum, ignoring women’s roles as situated economic actors within a system guided by logics of exchange that are ‘embedded in indigenous social and cultural frameworks’.

These findings also highlight the problems that occur when the economy itself is treated as a gendered vacuum, ignoring women’s roles as situated economic actors within a system guided by logics of exchange that are ‘embedded in indigenous social and cultural frameworks’.

Women’s position within these frameworks is ambiguous. While they provide opportunities for status and security to be enhanced, they may also expose women to coercion and gendered harm. It might be tempting to conclude, therefore, that these relational rhythms, principles and practices are outmoded and have had their day. But as I have made clear, globalised models of economic exchange do not sweep everything up in their path quite so comprehensively.

To ignore the insistence of alternative logics that shape economic life in conflict-affected settings means we may diminish the ambiguity too easily: the potential for women to benefit when we put economics at the heart of conflict transition but also the gendered insecurities and cruel gendered violence that these programmes might amplify. This is, surely, too heavy a price to pay for peace.

The Price of Peace? Frictional Encounters on Gender, Security and the ‘Economic Peace Paradigm. New Directions in Women, Peace and Security, (pp 41-60).