In this blog Christine Chinkin argues that the UN General Assembly’s 2017 Declaration on the Right to Peace overlooks women and their security concerns by failing to incorporate key aspects of the Women, Peace and Security agenda, and by ignoring a long history of women’s peace activism.

On 2 February 2017 the UN General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Right to Peace, previously adopted by the Human Rights Council, thereby locating the right to peace squarely within the framework of human rights. Although the pillars of the UN are peace and security, development and human rights, the concept of a right to peace has had a complex history within UN bodies. There is no right to peace in the International Bill of Rights but the Cold War saw the Declaration on the Right of Peoples to Peace seeking “above all, to avert a world-wide nuclear catastrophe” and pursuit of a culture of peace as the objective of UNESCO: “That since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed…That a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind.” More recently, formulation of a right to peace has been the objective of an open-ended working group of the Human Rights Council which saw contestations as to the desirability and feasibility of such an entitlement.

The General Assembly’s Declaration recognises that peace is more than absence of conflict and that it entails “a positive, dynamic participatory process where dialogue is encouraged and conflicts are solved in a spirit of mutual understanding and cooperation, and socioeconomic development is ensured”. Nevertheless it is a two-headed beast. One aspect is that it is heavily imbued with the traditional international institutional concerns for the maintenance of international peace and security – state sovereignty, the prohibition of the use of force in international relations, non-intervention, self-determination, an end to foreign occupation and alien domination, and, reflecting the contemporary geo-political landscape, the fight against terrorism.

The other is its human rights language so that “everyone has the right to enjoy peace such that all human rights are promoted and protected and development is fully realized.” Values such as tolerance, dialogue, cooperation and solidarity among all human beings, peoples and nations of the world are extolled as means of fostering peace, and institutions of peace education are promoted for their role in strengthening these values.

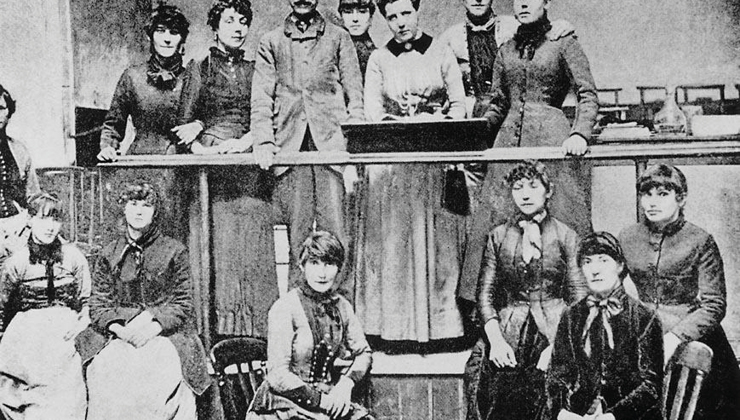

But there is a glaring gap in the Declaration – women. There are many landmarks in women’s activism for peace. In 1915, in the midst of World War One, women at the first International Congress of Women adopted resolutions for the ending of war that they forwarded to the warring Governments and sought input into the peace process. In 1985 under the banner of ‘Equality, Peace and Development’ the Third World Conference on Women agreed that “Peace includes not only the absence of war, violence and hostilities at the national and international levels but also the enjoyment of economic and social justice, equality and the entire range of human rights and fundamental freedoms within society.” In 1995, the Fourth World Conference on Women recognised that “Peace is inextricably linked with equality between women and men and development” and recommended women’s participation in conflict resolution in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

Frustrated with the failure to give effect to the recommendations from Beijing, women activists targeted the Security Council and saw the adoption of the first Security Council Resolution on Women and Peace and Security on 31 October 2000, Resolution 1325. Followed by ten other resolutions, the Women, Peace and Security agenda is now well entrenched. But the explicit and unique linkage made between Women and Peace and Security finds no place in the General Assembly’s Declaration on the Right to Peace. While some human rights instruments are listed those explicitly for the advancement of women’s rights are not included.

The need for “special and positive measures, for furthering equal social development and the realization of the civil and political, economic, social and cultural rights of all victims of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance” is rightly recorded but there is no such recognition of the harmful consequences for individuals, families and communities of sex and gender-based discrimination, misogyny and patriarchy. Indeed the only mention of women in the Declaration is the instrumentalist assertion that “the full and complete development of a country, the welfare of the world [no less] and the cause of peace require the maximum participation of women, on equal terms with men in all fields.”

Three thoughts come to mind. First, to argue for the inclusion of women in a Declaration on the Right to Peace is not to endorse an essentialist view of women as peaceful, or as inherently suited to act as peace-makers. Rather it is to argue that failure to recognise that continuing gender inequalities and violence against women undermines peace that cannot be achieved without ensuring security – freedom from fear and freedom from want – for all persons. These are what the Women, Peace and Security agenda, a potentially transformative human rights blueprint, contributes to and accordingly should, at least, have been referenced.

Second, “tolerance, dialogue and cooperation… are [undoubtedly] among the best guarantees of international peace and security.” However, these values must not be misplaced so as to maintain an unequal and oppressive status quo. Women should not be tolerant of the abuses they endure, even if their anger causes social disruption and threatens peaceful relations. Dialogue is meaningless unless it is inclusive. Despite consistent calls for their participation, women’s place in dialogue remains irregularly implemented at national and international levels. As recognised in Security Council Resolution 2242 on Women, Peace and Security, “engagement by men and boys as partners in promoting women’s participation in the prevention and resolution of armed conflict, peacebuilding and post-conflict situations” is important but unless this is through genuine cooperation and equality, it will not contribute to peace. Nor will it do so if the agenda for dialogue is determined only by men. Therefore, there is a danger that the gender neutrality of the Declaration on the Right to Peace will conceal the gender-specific obstacles to peace and security for women.

Finally, the Declaration highlights the disconnect between human rights and security, between the General Assembly and its subsidiary organ, the Human Rights Council and the Security Council; there is a failure to link their respective agendas to provide a coherent approach. The current situation poignantly shows the need for such cooperation and a coherent approach to tackling crisis, not just between organs of the UN but between countries and populations. Women’s participation is at the forefront in the home, in medical facilities, in community organisation; it is important that their contributions are not discounted as women’s usual caring roles simply magnified by the exceptional circumstances. Women’s expertise and experiences must be central to policy-making in the changed world that will inevitably ensue where the focus must be on a more equal, peaceful world.

This blog was written with the support of an Arts and Humanities Research Council grant and a European Research Council (ERC) grant under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 786494)

Image by thewet nonthachai from Pixabay