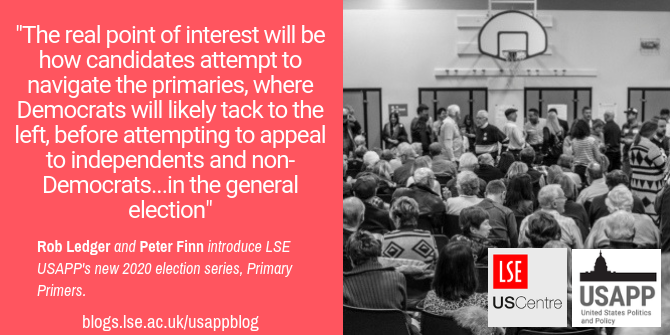

With barely a pause for breath following the 2018 midterm elections, the 2020 primary election race is now unfolding. Rob Ledger and Peter Finn introduce USAPP’s Primary Primers series and preview some important 2020 election themes: the importance of government dysfunction, candidates’ fundraising abilities, the rapid evolution of the Democratic Party, and whether or not President Trump may see a Republican challenger in 2020.

With barely a pause for breath following the 2018 midterm elections, the 2020 primary election race is now unfolding. Rob Ledger and Peter Finn introduce USAPP’s Primary Primers series and preview some important 2020 election themes: the importance of government dysfunction, candidates’ fundraising abilities, the rapid evolution of the Democratic Party, and whether or not President Trump may see a Republican challenger in 2020.

- This article is part of our Primary Primers series curated by Rob Ledger (Frankfurt Goethe University) and Peter Finn (Kingston University). Ahead of the 2020 election, this series explores key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define the US presidential primary process. If you are interested in contributing to the series contact Rob Ledger (ledger@em.uni-frankfurt.de) or Peter Finn (p.finn@kingston.ac.uk).

It is three months since the 2018 US midterms, an election that saw control of the House of Representatives handed to the Democrats, thus breaking the Republican’s two-year monopoly over the presidency, House of Representatives and the Senate. Most immediately, this result allows the Democrats to push back against the Trump administration. Looking forward, however, the midterms have set the stage for the 2020 presidential elections. Indeed, although the 2020 primary season is still a year away, Democratic contenders have already begun to jostle for prominence in an already crowded, and still expanding, field.

This article is the first of a new series we’re curating: Primary Primers. In it, we and others will explore a number of the key themes, ideas, concepts, procedures and events that shape, affect and define US presidential primary processes. The main focus of this series will be the build up to the 2020 presidential election. However, we will also explore topics, such as the differences between primaries and caucuses and the role of money within the US political system, with longer-term relevance. We begin this process below by considering a number of themes, some long-term some more immediate, that are likely to shape the lead up to the 2020 Presidential elections.

Dysfunction

Shutdowns have become a feature of US politics, with the most recent marathon government closure (which could re-start in mid-February) being the third of 2018. Polling suggests Trump, at least in the short-term, is taking the blame for recent events. This means the public may point the finger at Republicans for the current crisis, something that happened in 1995 (when Republican House Speaker Newt Gingrich prompted a shutdown after being made to travel in the rear cabin of Air Force One). Moving forward, however, negative implications for Democrats cannot be discounted, especially if stop-start shutdowns continue for months on end.

Credit: “Precinct 61” by Phil Roeder is licensed under CC BY 2.0

One of the consequences of the 2018 midterms was that the Democrats appear to have shifted left, although the extent of this shift will become clearer over time. While Trump himself has made building a border wall, the reason for the current impasse, a totemic issue. With the President having doubled down on the issue as part of a strategy designed to please his base. With these factors in mind, a compromise may be a tricky proposition. American voters will probably see the shutdown along partisan lines and as further proof of Washington dysfunction, with dissatisfaction potentially feeding right wing anti-government sentiment.

Others are trying to restore some sobriety to events and reinforce the core Democrat principle that government is a force for good. Interestingly, Hawaii Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard, in an attempt to move to the centre (bipartisan) ground, has distinguished herself from the broader Democratic field by blaming both sides of the political divide for the shutdown. This, along with previous positions Gabbard has taken on LGBT issues (about which she has expressed regret), may prevent her gaining traction, especially if the Democratic primaries are driven by the left.

Money

Money is a long-term issue within US politics, with millions needed to run campaigns at state level in many places. After the 2010 Citizens United Supreme Court decision, which removed a cap on campaign spending, there have been widespread fears that so-called super-PACS (funding vehicles that can accept unlimited contributions) could simply buy elections. Interestingly, the advent of a campaign orchestrated by a tycoon with the ability to contribute millions to his own campaign (Donald Trump) and a crowd funded campaign that rejected the use of super-PACs (Bernie Sanders) in 2016 challenged this thinking somewhat. Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign raised $1.2 billion. Yet, Trump raised approximately half of this ($646.8 million). So far, California Senator Kamala Harris and Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, among others, have pledged to shun super-PACS.

Current Front Runners

So far the Democrats many thought would run are proving the predictions correct by declaring. Warren, Harris, New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand and New Jersey Senator Cory Booker are probably the best known of those already declared. Observers expect politicians with name-recognition, such as the septuagenarians Sanders and Joe Biden, as well as the relatively young pretender Beto O’Rourke (46), to declare this year. The real point of interest will be how candidates attempt to navigate the primaries, where Democrats will likely tack to the left, before attempting to appeal to independents and non-Democrats, maybe even never-Trump Republicans, in the general election.

With such a crowded field (remember those epic Republican debates from last time?), it is a fool’s errand to try and predict a likely winner at this stage. Moreover, one must remember that the last three times establishment figures have been put up by the Democrats in presidential races (Hillary Clinton, John Kerry, Al Gore), a Republican entered the White House instead. Remember, Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, hard as it is to imagine now, both challenged establishment thinking to win the Democratic nomination. With a feverish mood among many Democrat supporters and new members of Congress, it seems likely a lesser-known, more progressive, figure will emerge. Moreover, tensions among the party’s different wings may abound if centrists, such as Ohio Senator Sherrod Brown, enter the fray, especially if they are seen as pushing back against party activists.

Left to Right – “2018.07.25 Kamala Harris at Ben’s Chili Bowl, Washington, DC USA 05269” by Ted Eytan is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0, “11a.FourteenthStreet.NW.WDC.13April2015” by Elvert Barnes is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0, “Beto For Texas!” by H. Michael Karshis is licensed under CC BY 2.0, “Bernie 2020 Heal America sign at the People’s Rally, Washington DC” by Lorie Shaull is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

What the Democratic Party is (and is not)

After the tumultuous changes of the 1960s, the Democratic Party consisted primarily of social liberals and blue collar workers, backed by the unions. This alliance splintered after a long period of electoral defeats, as Bill Clinton and the ‘New Democrats’ articulated a triangulation strategy generally more business-friendly than their predecessors. Obama and subsequently Clinton were more or less faithful to these ‘Third Way’ tenets. After Hillary Clinton’s catastrophic loss to Trump in 2016, however, followed by last November’s midterms, the party appears to have ditched the Third Way. Categorising contemporary Democrats as more left wing, however, does not translate simply into a retro version of the 1960s party. The left of today’s party are animated by a number of issues: the environment, the celebration of an encouraging array of identities and a humanitarian approach to migrants, to take three examples, which do not necessarily fit well into a pre-Third Way understanding of the Democratic Party.

A Republican challenge to Trump?

It currently appears unlikely Trump will face any kind of sustained challenge from within the Republican Party for the 2020 nomination. However, if the next year sees more government shutdowns, a critical report from Robert Mueller and continued dysfunction within the White House, some kind of sustained Republican challenge may coalesce. Though unlikely to succeed, those involved may see such a push as a way to define themselves, and the Republican party, beyond Trump, regardless of whether he wins or loses in 2020. Perhaps the most obvious candidate to spearhead such a challenge would be Utah Senator, and former Republican presidential nominee, Mitt Romney, who is secure in his senate seat until 2024 and has been openly critical of Trump.

—

There’s nothing like a Presidential run (real, imagined or mooted) to raise a profile in the US. Trump’s 2016 campaign was initially dismissed as a public affairs exercise and whether the insinuation carried any weight is still open to debate. Nevertheless the list of personalities threatening to run in 2020 is expanding weekly. Clearly the likes of Warren, Biden and Sanders are seen by all as serious contenders in this race. Moreover, there are a range of pretenders such as Harris and O’Rourke that, even if they are unsuccessful this time seem poised to help define the Democratic Party for decades. Finally, there are likely a number of candidates who, looking to develop their national profile or eying statewide office, will see involvement in the jockeying of the next year and a half as a vehicle to define themselves beyond their current position.

US politics can seem like a neverending media frenzy, a trend that has been intensified by the current incumbent of the White House. The possibilities for 2020 and beyond, however, are myriad. Certainly it gives political scientists food for thought. Over the coming months the Primary Primers series will consider the issues, events and personalities that will shape the 2020 presidential race.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

About the authors

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn – Kingston University

Peter Finn is a multi-award-winning lecturer in Politics and PhD candidate at Kingston University. His research is focused on conceptualising the ways that the US and the UK attempt to embed impunity for violations of international law into their national security operations. He is also interested in US politics more generally, with a particular focus on presidential power. He has, among other places, been featured in The Guardian, The Conversation, Open Democracy and Critical Studies on Terrorism.

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger – Schiller University

Robert Ledger has a PhD in political science from Queen Mary University of London. He has worked for the European Stability Initiative, a think-tank in Brussels, lectured at several universities in London and currently lives in Frankfurt am Main. He is a Visiting Researcher (Gastwissenshaftler) in the History Seminar at Goethe University and also teaches at Schiller University Heidelberg and the Frankfurt School of Finance & Management. He is the author of Neoliberal Thought and Thatcherism: ‘A Transition From Here to There?’