The money bail system widely used throughout the American criminal justice system requires a defendant to pay a specified sum of money or await their trail from a jail cell, placing undue burden on the poor. New research by Dottie Carmichael, Heather Caspers, Nicholas Davis, Trey Marchbanks, George Naufal and Steve Wood focuses on the use of validated risk assessment tools, which considers factors shown to predict bail failure to quantify the risk that a defendant might pose to the community. They find that this release mechanism can increase the number of people released without financial requirements, producing better outcomes for defendants and their families, and reducing downstream costs and safety concerns for taxpayers.

The money bail system widely used throughout the American criminal justice system requires a defendant to pay a specified sum of money or await their trail from a jail cell, placing undue burden on the poor. New research by Dottie Carmichael, Heather Caspers, Nicholas Davis, Trey Marchbanks, George Naufal and Steve Wood focuses on the use of validated risk assessment tools, which considers factors shown to predict bail failure to quantify the risk that a defendant might pose to the community. They find that this release mechanism can increase the number of people released without financial requirements, producing better outcomes for defendants and their families, and reducing downstream costs and safety concerns for taxpayers.

Within US state court systems, the ability to pay financial bail often determines whether or not defendants are released while awaiting the resolution of their criminal charges. In most jurisdictions, the path through the pre-trial stage is fairly linear. After arrest, a judge determines a financial amount that she believes will ensure the defendant will make court appearances and avoid new criminal activity if released from custody. If the accused has sufficient resources to pay the monetary sum, then they can return to the general population to await their eventual trial. If they cannot meet the financial obligations of bail, however, then the defendant must await their trial from a jail cell—a scenario that, in the extreme, led to the three-year detention of Kalief Browder in Rikers Island prison.

In a newly released study commissioned by the Texas Office of Court Administration and the Texas Indigent Defense Commission, our research explores several reasons why a pre-trial risk assessment program is preferable to the traditional bail system outlined above. Rather than tying pre-trial release to financial solvency, this assessment tool considers whether a defendant’s individualized risk might be a better way to ensure court appearance and prevent new criminal activity. By considering a number of factors shown to predict bail failure – things like the age of a defendant, criminal past, and current charges – a risk assessment tool quantifies the risk that a defendant might pose to the community. A defendant’s release, then, is based not on their (in)ability to pay money bail, but on the objective likelihood that they pose a danger to the public.

So, what does the data say? Consider, first, that victim costs are 72 percent lower in the Texas county studied where risk assessment is used. Money bail systems more often release dangerous people who can pay a sum of money, while individuals who pose little meaningful risk to other citizens, but are otherwise too poor to cover their bail expenses are left sitting in jail until trial. Our analysis indicates that three times more low-risk defendants are detained on a low bond in the financial release system than one that utilizes risk-informed release. This inefficiency is compounded by a second sobering statistic. Our analysis shows that 22 percent more new crimes – including 1.5 times more felonies and violent crimes – were committed by people on financial release, implying that the public is safer when a pre-trial risk assessment system is implemented.

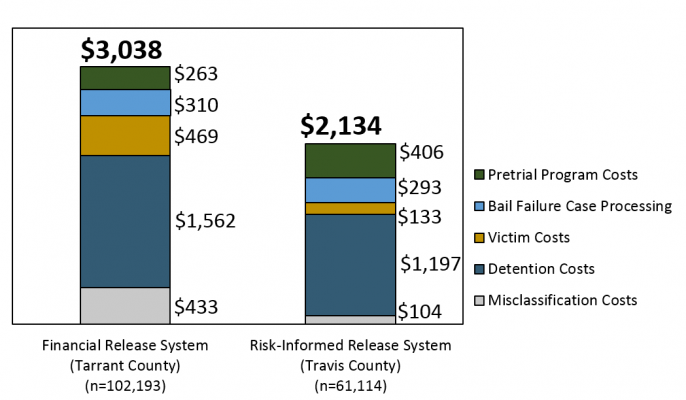

Figure 1. Total pretrial cost per defendant. Estimates account for the predicted costs associated with programs to supervise pretrial defendants, pretrial detention, and costs of bail failure.

Estimates account for the predicted costs associated with programs to supervise pretrial defendants, pretrial detention, and costs of bail failure.

Second, as Figure 1 illustrates, combined court processing and detention costs are 31 per cent lower where risk assessment is used (detailed analysis of how these estimates are derived is available here). Defendants in a money bond system spend longer in jail on average because they either cannot afford to post bond, or because re-offense rates are higher where risk is not considered for release. As a result, money bond can have significant downstream financial consequences. Whereas the total costs associated with risk-informed pre-trail release are $2,134 per defendant, the costs associated with release based on one’s ability to pay a financial bond are almost $3,100. Even including the cost of pretrial programs to help moderate-risk defendants succeed in the community, pretrial risk assessments reduce the costs associated with the prevailing bail system by 30 per cent.

The social costs associated with an inability to post bond are also profound. When pretrial custody is determined by risk, 10 times more people are released compared to the system based on financial bonds. This means people are much less likely to be incarcerated due to poverty: In the money-based system, at least three times more people are held on a bail at or below $500. Why does this matter? Spending more time in jail reduces the likelihood that defendants will retain their jobs, which are necessary to not only pay for one’s legal fees but also to plan a strong defense and provide for one’s family. Further, spending additional time in jail can prove catastrophic for the stability of the familial unit.

Some states like Colorado, Maryland, and New Jersey have experimented with this alternative to the money-bond system. Opposition to these changes largely hinges on whether or not risk assessments remove judicial discretion and pose a threat to public safety. Certainly, no tool is perfect and, while risk assessments cannot totally remove the threat of re-offense, neither can the prevailing money-bond system. However, this study provides firm empirical evidence that shows that, on average, pre-trial risk assessments are associated with less new crime than the money bail system.

Under conditions of intense polarization and gridlock, which characterize both state and federal legislatures in the United States, there are few policies upon which liberals and conservatives find agreement. Yet, there does appear to be some bipartisan interest in working toward reforming the bail system. Our findings also suggest that, at least among the spectrum of pretrial professionals and judges who work within this system, there is both consensus and optimism that these institutional changes can positively affect pretrial processing. Not only would policies supporting widespread use of risk assessment tools help address some of the ballooning costs associated with managing state bureaucracies, but these reforms contribute to a fairer and more efficient system of criminal justice.

“Chance” by Jacques Lebleu is licensed under CC-BY-NC-2.0.

This article is based on a recently published report, Liberty and Justice: Pretrial Practices in Texas.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2k5lK0J

_________________________________

Dottie Carmichael – Texas A&M University

Dottie Carmichael – Texas A&M University

Dottie Carmichael is a Research Scientist at Texas A&M’s Public Policy Research Institute (PPRI) and has headed a fifteen-year program of research on behalf of the Texas Indigent Defense Commission (TIDC). Her research primarily focuses on the criminal and juvenile justice systems and has been cited by the US Departments of Justice and Education, by President Barak Obama in a February 2014 speech launching the “My Brother’s Keeper” initiative, by the US Education Department’s Office of Civil Rights, and in written opinion by the Supreme Court.

Heather Caspers – Texas A&M University

Heather Caspers – Texas A&M University

Heather Caspers is a Research Associate at the PPRI. Her work has been featured in a number of PPRI studies, in addition to academic journals. Her ongoing work covers criminal justice issues, including indigent defense.

Nicholas T. Davis – Texas A&M University

Nicholas T. Davis – Texas A&M University

Nicholas T. Davis is an Assistant Research Scientist at the PPRI. His research has been published in a number of scholarly journals and mainstream news outlets. Aside from policy work on indigent defense, his ongoing research explores the conditions under which citizens value compromise and, more broadly, democracy.

Trey Marchbanks – Texas A&M University

Trey Marchbanks – Texas A&M University

Trey Marchbanks is an Associate Research Scientist at the PPRI. His research has been featured on National Public Radio, presented before the United Nations, and appeared in both scholarly and mainstream outlets. His expertise is in the use of advanced statistical methodologies to answer public policy questions.

George Naufal – Texas A&M University

George Naufal – Texas A&M University

George Naufal is an Assistant Research Scientist at the PPRI and a research fellow at the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA). His work has appeared in several academic journals and mainstream newspapers. He is also the co-author of the book “Expats and the Labor Force: The Story of the Gulf Cooperation Council Countries” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012). He studies applied econometrics with applications to labor economics including education, migration, demographics and unemployment.

Steve Wood – Texas A&M University

Steve Wood is a former Assistant Research Scientist at the PPRI.