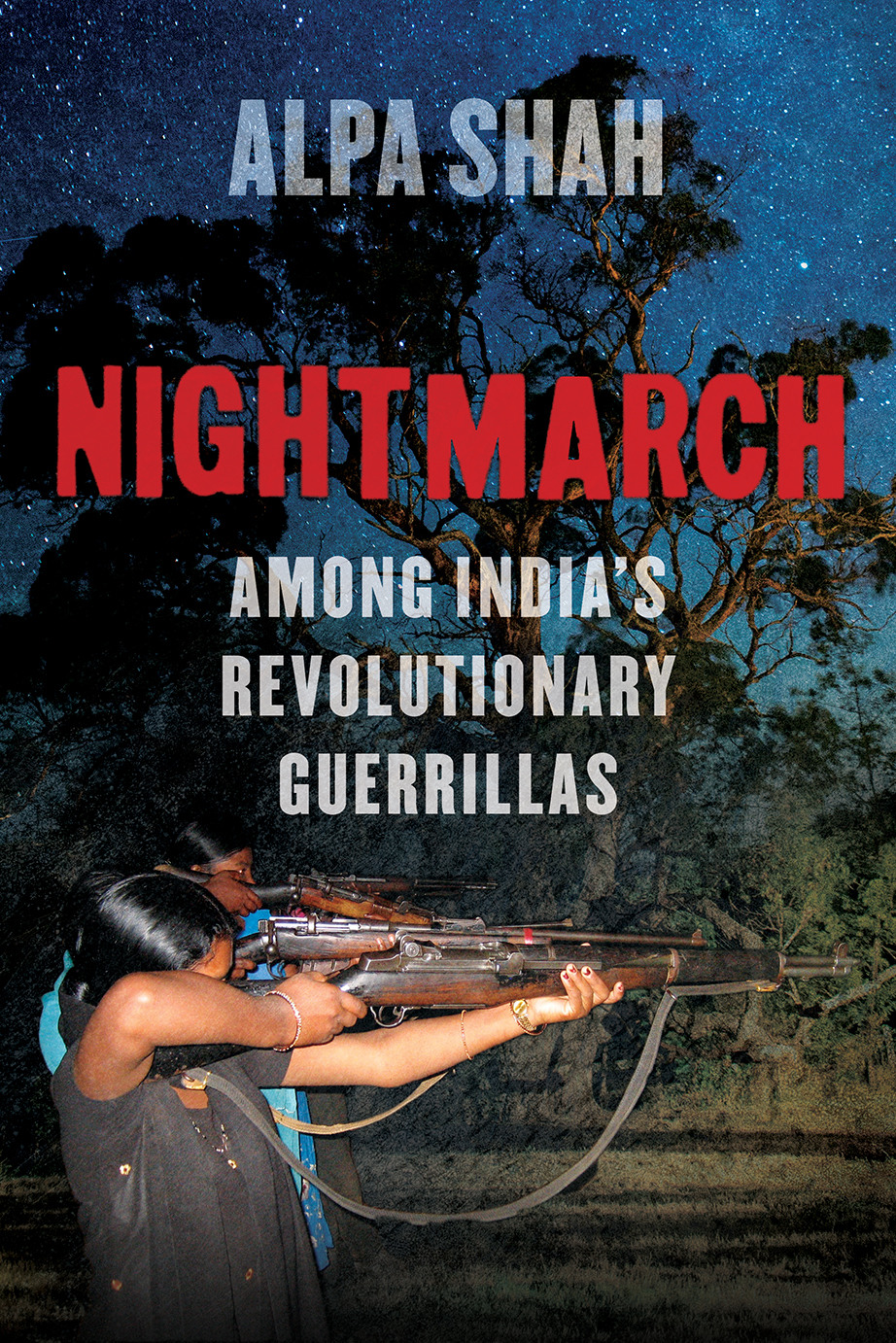

Labelled as ‘terrorists’ by the Indian state, Dr Alpa Shah (LSE’s Associate Professor of Anthropology) embarked on a seven-night trek in 2010 with the Naxalites, communist guerrillas who have been engaged in a decades-long battle with the Indian state. Here she discuss her new book on that journey, Nightmarch, where she went to find out why some India’s poorest people have taken up arms.

Your latest book is a first-hand account of spending time with the Naxalites – who are they?

Inspired by Marx, Lenin and Mao, the Naxalites are the world’s longest-running armed revolutionary struggle. They say they are fighting inequality and injustice to bring about a more equal communist society. They first made their mark in May 1967 in the West Bengal village of Naxalbari, from which they get their name. Peasants and labourers occupied land, reclaimed it as theirs, demanded that the landlords cancel all their debts and end intergenerational bondage. Although this initial rebellion was savagely crushed, over the years it continued to inspire movements for social change across India.

Drawn by the romance of revolution, many educated urban youth from well-to-do and dominant caste backgrounds renounced the comforts of their homes and university classrooms in order to work with the rural poor. Over the decades, they attracted some of India’s most disenfranchised people – its low caste and tribes – to join their fight for a better world. Today, the largest Naxalite group has an armed guerrilla force of less than 10,000 and calls itself the Communist Party of India (Maoist), or Maoist for short. Its strongholds are in the hills and forests of central and eastern India that are the home of India’s tribal people, popularly called Adivasis, and with whom I lived for four and a half years.

What did your seven-night trek with them and years of living in their guerrilla strongholds reveal about their aims and methods?

What did your seven-night trek with them and years of living in their guerrilla strongholds reveal about their aims and methods?

In a world of increasing extreme inequalities, the Naxalite desires are noble but their struggle is fraught with contradictions and tensions which constantly undermine their aims.

Though it is rare to get people who are willing to sacrifice their lives for a better world, taking up arms against oppression comes with all kinds of problems. Under intense state repression it is easy to reproduce the violence of the oppressor, and to also regenerate caste, tribe and gender inequalities within the revolutionary struggle. The hopeful dreams of beautiful futures can easily turn into nightmarish power battles between warring elites leaving behind the destruction of countless lives in vicious cycles of violence.

What has the Indian state’s response been to them?

The Indian government has labelled the guerrillas ‘terrorist’ and, over the last ten years, run brutal counterinsurgency campaigns promising to wipe out the rebels. Human rights activists claim that there is a direct link between economic growth and the latest military onslaught. National and multinational corporations are waiting to harvest lucrative mineral resources which lie under the Adivasi forests of central and eastern India.

The Adivasis, and the Naxalites who live among them, are in the way of India’s economic boom. In the last decade, almost 7,000 people have been killed because of the conflict. More than 100,000 government soldiers were dispatched to surround the guerrilla strongholds. The prisons of the region are flooded with people incarcerated for allegedly being Maoist or sympathising with their cause. In some parts of the country, local youth were armed to attack their neighbours. Entire villages were burned down, children thrown into fires and pregnant women killed; many women were raped, others were mutilated and murdered, and hundreds of thousands of people were forced to leave their homes. It does feel like a slow deadly clearing of the area.

What is next for your research?

I’ve been leading a programme of research exploring how and why India’s low castes and tribes – its Adivasis and Dalits – who make up 1 in 25 people in the world, remain at the bottom of the economic and social hierarchy despite economic growth. We just published a book, Ground Down by Growth, which explores the ways in which capitalism is entrenching social inequality. There’s a lot of work still to be done on these issues. I’m also acutely aware of the need to take time to reflect on what’s next.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the South Asia @ LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before posting.

This piece originally ran in LSE Connect.

Nightmarch: among India’s revolutionary guerillas by Alpa Shah is out now. Listen to the podcast of Alpa Shah’s book launch talk on Thursday 1 November 2018.

Alpa Shah is Associate Professor – Reader in Anthropology at LSE. She read Geography at Cambridge, trained in Anthropology at the LSE, and taught anthropology at Goldsmiths until 2013 when she returned to the LSE.