Poonam Gupta and Arvind Panagariya examine whether Indian voters care about economic outcomes.

Despite the intuitive appeal of the idea that good economic outcomes such as sustained rapid growth should help incumbents win elections, evidence on it has been scant, especially from developing countries. In one notable exception, Brender and Drazen (2008) use a comprehensive cross-country dataset spanning over 74 developed and developing democratic countries and 350 election episodes to examine whether Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth during the term in office or in the election year helps incumbents win elections. They find that on average, growth helps incumbents win elections in developing countries, but not in developed ones.

We contribute to this literature by studying the link between growth and electoral success in India using data on the 2009 parliamentary elections. We consider the effects on election outcomes of candidate characteristics, party affiliation, and the economic performance of the incumbent government. We find growth in a state to be by far the most important determinant of the fortunes of the candidates nominated by the party ruling in that state. The higher the growth rate in the state, the larger is the proportion of the ruling party’s candidates winning their seats. While candidate characteristics and their party affiliations matter as well, these turn out to be quantitatively less significant.

Economic performance and incumbency advantage

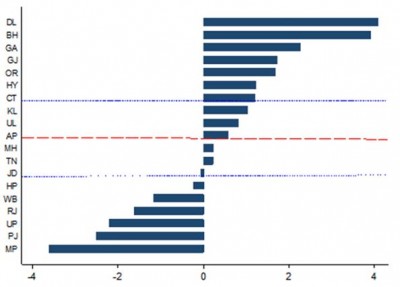

In Gupta and Panagariya (2011), we measure performance by the average economic growth in the states from the beginning of the fiscal year 2004–05 to the end of 2008–09. In Figure 1, we depict the deviation of the average growth in the state domestic product from the national GDP growth for each of the 19 states we analyse, with the states stacked in declining order of their growth rates.

Difference between the average growth rate of state domestic product and the GDP growth rate (2004–2008). Source: Gupta and Panagariya (2011).

Difference between the average growth rate of state domestic product and the GDP growth rate (2004–2008). Source: Gupta and Panagariya (2011).

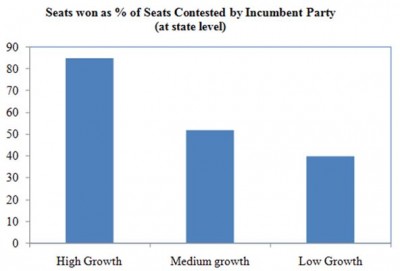

The key question we ask is: What proportion of the candidates fielded by the state incumbent party won the national election? The outcome is depicted in Figure 2. The average proportion of the incumbent party’s candidates winning the election in high-growth states was an impressive 85 per cent. In contrast, those in medium- and low-growth states on average won only 52 per cent and 40 per cent of the seats contested, respectively. In Gupta and Panagariya (2014), we obtain this strong relationship between growth performance and election outcomes in systematic econometric analysis. Quantitatively, the effect of growth is much larger than the effect of candidates’ personal characteristics or their party affiliations.

Proportion of the candidates of the incumbent party in the state winning the national election (sorted by states’ growth rates). Source: Gupta and Panagariya (2011).

Proportion of the candidates of the incumbent party in the state winning the national election (sorted by states’ growth rates). Source: Gupta and Panagariya (2011).

Conclusion

What does our analysis imply for the ongoing parliamentary elections? If this election were to play out like the 2009 election, the outcome would once again be the aggregate of the state-level outcomes, with the latter influenced the most by the economic performance of the state. But some factors are likely to ameliorate this effect this time round. First, there now appears to be a ‘wave’ factor at work in the election. Opinion polls suggest that many voters in northern India are attracted to the prime ministerial candidate of the opposition Bharatiya Janta Dal (BJP) party, and therefore may vote for the BJP candidates regardless of the performance of the state. Second, in the recent subnational elections concluded in December 2013, a new party known as the ‘Aam Admi Party’ (AAP) has emerged on the scene. This party has put the fight against corruption at the forefront of the national agenda, and has acquired some national prominence. Whether this party takes away votes from the Congress, the BJP, or some of the regional parties may have a determining influence on the outcome. In an election with three or more serious candidates, even a shift of one per cent or two per cent of voters can alter the outcome in a major way.

This post originally appeared on VoxEU and was also published by Ideas For India. Click here for the complete article, including analysis of the effects on election outcomes of candidate characteristics and party affiliation.

References

Brender, Adi and Allan Drazen (2008), “How Do Budget Deficits and Economic Growth Affect Reelection Prospects? Evidence from a Large Panel of Countries”, The American Economic Review, 98(5): 2203–2220.

Gupta, Poonam and Arvind Panagariya (2011), ‘Economic reforms and Election Outcomes’, in Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya (eds.), India: Trade, Poverty, Inequality and Democracy, New York: Oxford University Press.

Gupta, Poonam and Arvind Panagariya (2014), “Growth and Election Outcomes in a Developing Country”, Economics and Politics, forthcoming.