The ‘European Health Union’ recently emerged as a cornerstone of the EU’s health agenda.

This term stems from a post-war project called the ‘White Pool’ that would integrate health services and social health insurances. Although that project never took shape, the S&D party rekindled interest in March 2020. This rekindling led to a Resolution adopted with overwhelming support in July 2020, which called for ‘far stronger cooperation’ and ‘a number of measures to create a European Health Union’.

The Commission named and set its agenda accordingly, by combining early lessons learned from the health crisis with the EU priorities for 2019-2024. Those priorities, in turn, are based on the Council’s intentions to address longstanding problems of health and governance across Europe.

Health is political. It is subject to the second biggest government expenditure in the EU, and is thus conceptualised as a building block of the European social contract. Although EU Treaties reserve health as a matter of national competence, health is also nonetheless inextricable from market concerns. Consequently, health presents a loophole through which the EU can regulate market failures.

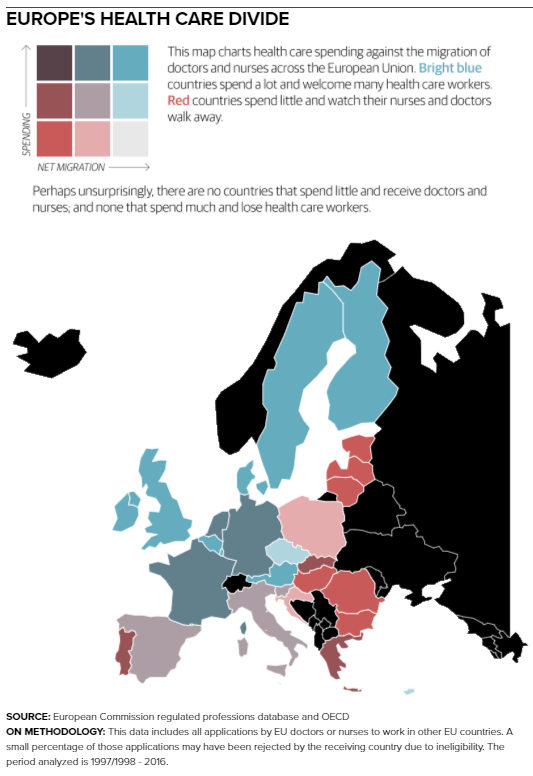

Be that as it may, the EU and Member States have different goals in their respective governance of health. On one hand, EU institutions are mandated to ensure ‘the competitive functioning of the markets’ and ‘a high level of human protection’; on the other hand, EU Member States are committed to promote ‘universal health coverage’. Those different incentives result in confused outcomes. For example, between 2009 and 2015, Romania lost half its doctors upon its accession to the EU. Other Central Eastern European countries showed similar results. These countries have yet few alternatives to benefit from or mitigate effects of the freedom of establishment granted to highly skilled professionals.

Source: The EU Exodus: When doctors and nurses follow the money, Politico

It’s worth tempering aspirations for a European ‘Health Union’ with a dose of realism. For example, Dr Vytenis Andriukaitis, the former European Commissioner for Health and Food Safety, conveyed mixed feelings about the European Health Union at Gastein’s European Health Forum in December 2020, when he voiced a Manifesto to all Members of Parliaments and European leaders for a better EU role in health.

A European Health Union must tread a fine line. It would need to be sufficiently robust to address health crises, yet it would also need to respect domestic health authorities. There’s no time like the present.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.