Although life as a teenager is now a distant memory, I still remember how fervently I believed that “my life would be over” were I to make a “wrong move”. Today’s crisis amplifies those feelings for some—especially young people expected to transition seamlessly to young adulthood.

Given formal education’s centrality to social mobility, successful education requires youth to be flexible to cope with current challenges. In developing countries, young people shoulder various tasks early such as helping in the family farm or business, cooking and cleaning, all while trying to keep up with education. Nationwide school closures from the pandemic means that young people need to juggle these tasks under greater constraints.

At first glance, it might appear preferable for children to focus on school and for families to protect children from work. However, learning happens in many forms and from many activities. Both work and school are important social and developmental activities for children in developing countries.

In an analysis of Young Lives (YL) data—a longitudinal study in four developing countries of the Global South—Morrow and Boyden (2018) show that children and parents in YL countries see economic work as a way to gain knowledge and learn new practical and social skills. Benefits include establishing a foothold in the labour market, and learning responsibility as ‘part of their adulthood’. Education is an important base for human capital accumulation, but there is less discussion around other activities which may also be important in building young people’s life skills, such as self-esteem and resilience. Now more than ever, life skills will be important in building resilience to overcome this trying time.

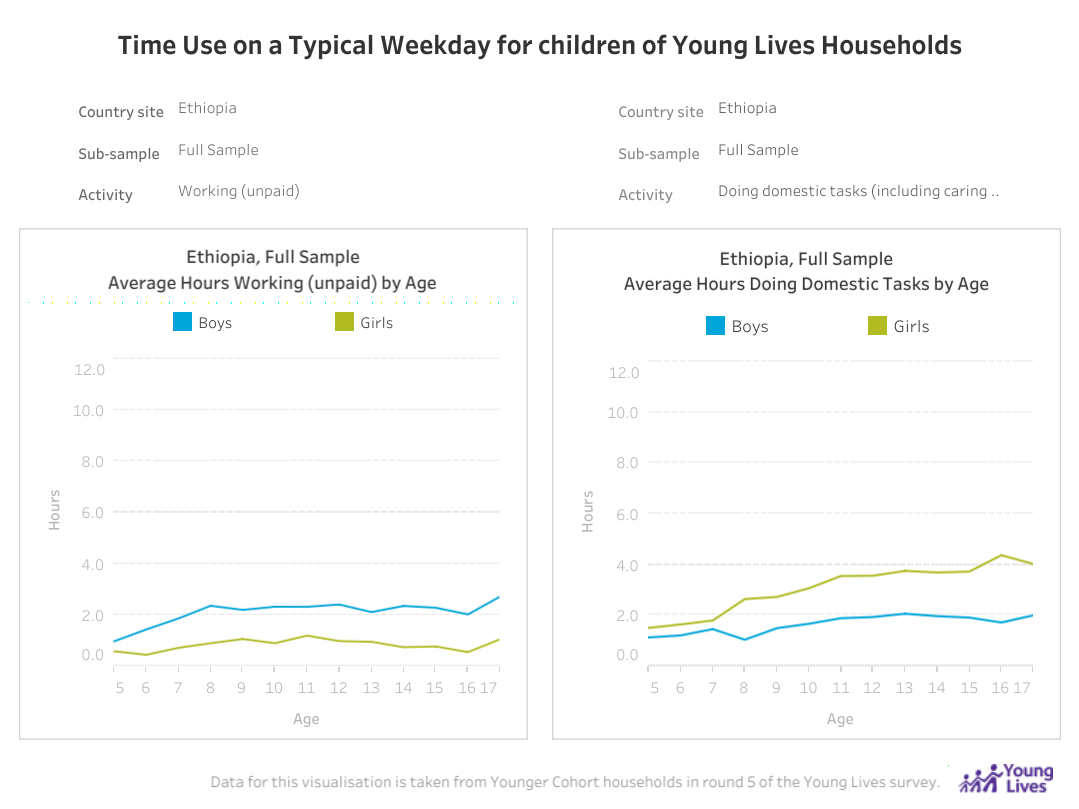

Using YL data, I study how different activities affect children’s self-esteem and self-efficacy. The data informs how children spend their time (and can be visualised here). I shift the discussion from the “trade-off” between work and school towards a more comprehensive analysis of how children spend their time, such as the interaction between economic work, domestic work, play, school and study.

My preliminary findings show that more time spent attending school or studying outside school is beneficial for children’s non-cognitive skills—especially in India and Vietnam. However, in Ethiopia and Peru, children may be able to balance work and educational activities without compromising their non-cognitive skills, so long as the increased time in work reduces time in leisure and not in the educational activities.

The effect of children’s time allocation on non-cognitive skills therefore differs by country. Local institutions and social norms that perceive value in, say, work encourage children to balance labour and education. Further, there is scope to learn from young people’s work experience in developing countries. For instance, developing countries that are still strengthening their education system could strengthen vocational training and incentivise entrepreneurship. Developed countries may think about reforming non-graduate career routes and effective apprenticeships.

As different countries respond to the current crisis, policy precedents will cast a long shadow. Now is the time to revitalise the discussion on equalising opportunity for youth.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.