A public health emergency at COVID-19’s scale demands solutions not only for new problems of viral pathogenesis, but also for old ones of much longer-standing diagnosis. Prisons and jails are among the more pressing sites of public health concern, as they confine staff and inmates in compressed space. In that context, solutions recently considered unthinkable have swiftly gathered an unfamiliar credibility.

Overcrowded prisons and jails are petri dishes of viral contagion. The modern prison was built to replace the fetid facilities that fomented ‘jail fever,’ but the dilapidated architecture of many correctional facilities proves just as bad today. The US Supreme Court has ruled that healthcare delivery in California’s prisons violates the protection against cruel and unusual punishment. The UK’s Prison Medical Service was disbanded in 2006 and placed under the care of the NHS following an excoriating review of healthcare in correctional facilities. The WHO has expressed concern about prison health throughout Europe as a whole, which COVID-19 has doubtless exacerbated.

Images such as this, of double- and triple stacked prison beds, formed part of the US Supreme Court’s opinion that healthcare delivery in California’s prisons failed to pass constitutional muster. Photo credit: Brown v. Plata (2011)

Contemporary prisons are not only risky places; they also house vulnerable occupants. The turn toward longer sentences in many penal systems has yielded an incarcerated population less protected from the threats COVID-19 poses. Across the world, the UNODC reports that elderly inmates—an especially high-risk population—have grown as a share of an already-expanding prison population at a rate that far outpaces that of younger inmates.

Piecemeal solutions prove too modest to confront the public health crisis in overcrowded custodial facilities. COVID-19 instead triggers something more ambitious than the case-by-case sentence relief for inmates deemed least likely to recidivate or the construction of ersatz prison wings to distance beds as sparsely as the World Health Organization recommends.

A more ambitious program may instead be taking hold. In the past week, ministers of state and international diplomats alike have echoed one another’s invitation to consider prisoner release programs to stem future contagion.

The UN’s High Commissioner for Human Rights has warned that failing to release vulnerable and low-risk people in detention risks violating the Mandela and Bangkok Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. The Council of Europe’s Committee for the Prevention of Torture has added that alternatives to deprivation of liberty are an “imperative” in overcrowded facilities.

Such calls for mass amnesty have resonated for some. Scotland’s justice secretary is “actively looking” at an early release order within the next few days. The head of the UK Prison Officers’ Association has expressed similar openness to prison release. Italy has already decreed that people serving sentences set to expire within the next 18 months will be subject to supervised early release. New York has authorized the release of over a thousand people incarcerated for parole violations from its jails. Many more were released from Los Angeles County’s jails earlier this week.

Sending fewer people to prison and jail also helps mitigate the crisis. Prosecutors in some jurisdictions have either been instructed or have exercised their considerable discretion to reprioritize charging cases more leniently. Doing so starves the virus by providing fewer bodies to incubate in overcrowded facilities in the first place.

Leniency toward people suspected or convicted of a crime provokes distaste about the public safety effects of choosing less punishment. The distaste is all the more pronounced when the choice to punish less applies categorically to an entire class of person rather than on an individual basis.

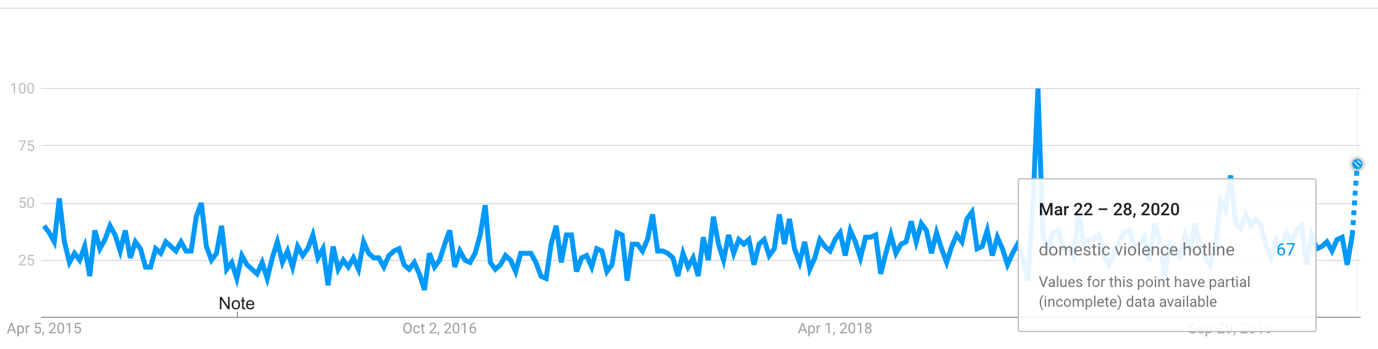

Some of that distaste is understandable. Criminological intuition holds that releasing many people from custody—especially during a lockdown when some will be forced indoors with a partner—may, for example, lead to a noticeable increase in domestic violence. An analysis of Google Trends shows that, with the exception of one week in early-January 2019 when President Trump restrictively redefined violence against women, Americans have googled “domestic violence hotline” more times this past week than any other in the past half-decade.

Google searches for “domestic violence hotline” have experienced a sharp increase in the last week. Photo credit: Google Trends

But general concerns about the criminogenic effects of prison release may well be overstated. Criminological evidence that predates the pandemic measured the public safety effects of prison releases in Italy, California, and Illinois. The results are reassuring: violent crime tends to remains relatively unchanged, and property crime reports at most a modest increase. Moreover, an analysis by the Marshall Project suggests that one effect of people spending more time indoors is that property crime may in fact be in abrupt decline.

COVID-19 layers new public health exigencies on top of the old ones. But efforts to reform overcrowded prisons have struggled against the belief that releasing inmates is either politically untenable or criminologically unwise. On the contrary, the current emergency offers a salutary reminder that the unthinkable is in fact anything but.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.