Communication and consultation were vital in building trust and leveraging existing trust between villagers and community leaders. Government-imposed measures that were viewed as inappropriate or disproportionately strict would have generated much less community buy-in, writes Emma Potchapornkul

_______________________________________________

Thailand’s conflict-affected southern border provinces of Pattani, Yala and Narathiwat (also referred to as the Deep South) narrowly avoided becoming a Covid-19 hotspot during the country’s first wave between March and June 2020. Returnees from religious mass gatherings abroad were considered a high source of risk as were Thai migrant workers in Malaysia, who were returning to the Deep South en masse following Kuala Lumpur’s 18 March announcement of border closures and imposition of movement control orders.

In the Deep South, the provincial governments were tasked with setting up quarantine facilities for returnees. Soldiers at military checkpoints switched from carrying guns to thermometers and the military was redeployed along the dense jungle-border to catch migrants attempting illegal border crossings. The region’s main insurgent group, the BRN, declared a unilateral ceasefire on humanitarian grounds. Local districts issued orders that pandemic mitigation measures were to be implemented although there was no accompanying guidance or financial support. For communities, this was nothing new. The central government is routinely criticised for overloading local administrations without providing adequate budget and capacity support (Nagai 2008).

This blog post explores how three southern border communities responded to the Covid-19 pandemic during this period. It is based on field visits and interviews by Peace Resource Collaborative (PRC), which were motivated by a desire to understand how some rural communities in Thailand’s conflict-affected Deep South coped with the pandemic. This blog finds that although the Covid prevention and mitigation measures adopted were relatively uniform, there was an interesting divergence when it came to how the measures were implemented and who led the implementation. These divergences are suggestive of the diverse modes of informal grassroots governance that operate alongside and, to greater or lesser degrees, either independently of or in tandem with formal structures of local government. Below, I introduce the findings from the three villages, with each section presenting who the key initiators were, what measures were implemented, what external support there was, and any prospect of future collaboration among parties involved.

Ban Rae Village 1 and 4, Thanto District, Yala Province

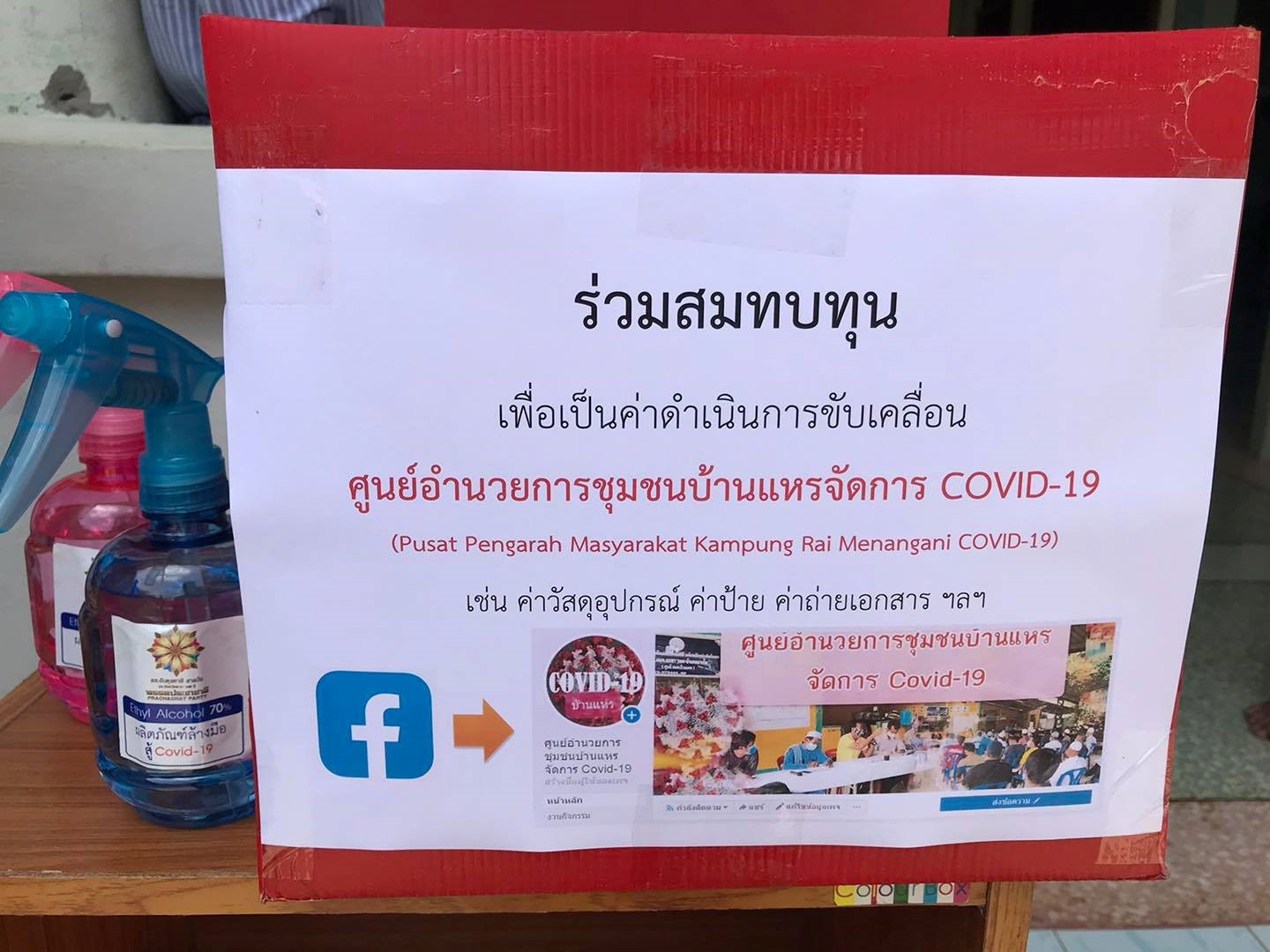

This community of approximately 1,600 villagers went into self-imposed lockdown in response to the discovery of six Covid cases in the surrounding district. Local youth drove the pandemic response and were credited with bringing together officials from different branches of local administration. This led to the establishment of the Ban Rae Covid-19 Relief Centre on 5 March. The bridge-building that the youth undertook is notable as administrative sectionalism is a recognised feature of Thailand’s local government system that has often led to poor horizontal coordination among government offices at these levels (Nagai 2008). These officials gave technology-savvy youth the autonomy to develop a suitable response yet provided support when needed.

Communication played a central role in getting community buy-in of lockdown measures. When villagers were unhappy about the mosque closure, the imam visited each household to personally explain the situation. When villagers questioned the need for strict mask-wearing in public or questioned village road closures, time and effort was taken to explain the rationale for the measures. Communication and consultation were vital in building trust and leveraging existing trust between villagers and community leaders. Government-imposed measures that were viewed as inappropriate or disproportionately strict would have generated much less community buy-in.

The Ban Rae community is aware that it is under military surveillance as part of counterinsurgency efforts. So, security agencies were not brought into the pandemic response and their involvement was limited to nightly manning of village checkpoints and donation of survival packs. In the absence of funds from the District Office, initial measures were financed by community leaders and villagers.

Following the end of lockdown restrictions, the Covid-19 Relief Centre adapted its functions to take on mediation of village disputes. To that end, it has begun work on generating collective agreements to resolve conflicts over water resources that tend to flare up between farmers in the dry season.

Ban La Wang, Si Sakhon District, Narathiwat Province

Ban La Wang had around 80 returnees from Malaysia and 60 from other Thai provinces, mainly Phuket and Bangkok. As a result, the area was considered high risk. The Si Sakhon District Chief called local officials from different administrative branches together and established Choeng Khiri Sub-District’s Covid-19 Management Centre. Before that, these key persons had had little prior contact. The manner of organisation is instructive. As noted above, administrative sectionalism is a well-known feature of local government, evidenced here with the acknowledgement that the officials involved had little prior contact. Yet, in contrast to the Ban Rae case, the District Chief acted as bridge-builder. District chiefs are appointed by the Ministry of Interior and have the statutory authority to direct and order government officials from other ministries and departments at the district level. Thus, what could be observed was the activation of a vertical chain of command to mobilise the pandemic response.

Returnees were required to self-isolate and their houses were cordoned off to alert the neighbours. However, not all returnees presented themselves to the village administration. So, a team of 25 volunteers conducted a systematic and tightly-controlled search of 500 households. The sub-district was divided into zones and volunteer pairs were assigned one zone consisting of 20 households. Villagers were encouraged to report households with high-risk individuals that had failed to present themselves to the village chief. Returnees, who refused to quarantine, were threatened with prosecution.

Security agencies were brought in as a last resort to deal with villagers that resisted lockdown measures. This was said to be quite effective in gaining compliance particularly as reports had been circulating of continued counterinsurgency operations targeting youth in surrounding communities. The sub-district administration’s emergency budget went into establishing quarantine facilities in schools and other makeshift sites. What remained was used to procure PPE and other supplies, which were distributed to communities. PPE donations also came from the military and a local university donated survival bags to vulnerable households.

Since local officials across different administrative branches collaborated at the behest of the District Chief, no future collaboration was envisioned except in the event of another outbreak.

Ban Sarong Village 3, Yaring District, Pattani Province

Ban Sarong Village 3 is the only village in this case study that recorded cases of Covid and the village was placed under lockdown by provincial order between April and May. Covid relief measures revolved around the Darul-Aman Mosque community of 460 households consisting of approximately 3,000 registered devotees. Measures were managed by the Islamic Committee of Darul-Aman Mosque and an informal village committee established by residents to address community problems. Decisions were made by consensus following joint consultations. The mosque committee was maintained through public donations and was supported by a 40-strong community youth network. In contrast to the other two cases described, Ban Sarong’s pandemic response appeared to be the most independent of the local government administration. Yet it was also the only community discussed here to have received an official lockdown order. Nevertheless, the committee described a good working relationship with the local administration, which was evidenced by their ability to negotiate with officials over certain lockdown measures.

The mosque committee’s rapid mobilization of youth volunteers demonstrated the cohesiveness of its existing organisational structure and its decision to take responsibility for Covid-19 health announcements demonstrated an ability to adapt quickly depending on the needs of the situation. By assuming responsibility for disseminating health information, the committee was able to challenge some of the fatalistic attitudes towards the virus. Furthermore, it helped to address some hostility that had emerged towards Village Health Volunteers, whose test and trace procedure was said to resemble military search and arrest operations.

Villagers are wary of the military so interactions are kept to a minimum and the military’s involvement was limited to donating survival bags. As local government support was slow to arrive, donations were actively sought, which came not only from the private sector but also from abroad suggesting the community had good external links to draw on for support.

It was expected that regular community activities would resume following the end of lockdown restrictions. With strong local leadership and a pre-existing management structure, there was little doubt that collaboration would continue in the future.

Concluding discussions

As noted earlier, the study of PRC was to understand how some rural communities in Thailand’s conflict-affected Deep South responded to the pandemic. In Ban Rae, youth-led bottom-up organising was central to their relief efforts and their self-organised process suggested that their collective action was not imposed by any one particular actor. In Ban Sarong, a well-established community management structure was based around the Darul-Aman Mosque, which already had the legitimacy to act on behalf of and in the interests of the community. Furthermore, community leaders quickly adapted their existing practices to meet the needs of the situation. For both Ban Rae and Ban Sarong, an essential ingredient was trust. Trust-based communication helped assuage concerns and ensured community buy-in of the pandemic measures. In keeping with this, the military, which is historically viewed with intense mistrust by the region’s ethnically Malay-Muslim community, was kept at arm’s length and their involvement was minimal in these two communities.

By contrast, Ban La Wang displayed an alternative pandemic response, one based on a different dynamic between local leaders and the community, and which reflected a more top-down official process that followed the formal lines of government authority. It was the only case where the military was on standby to play a more active role. The Ban La Wang community differed from the Ban Rae and Ban Sarong communities in two distinct ways. Firstly, it was economically much less secure than the other two communities. As such, it had fewer of its own resources to draw on for support. Secondly, there appeared to be far less social cohesion within the community. Thus, an externally imposed response may have been necessary to mitigate the risk posed by the high number of returnees to the area.

These communities had come to our attention through stories shared online by local media outlets highlighting positive examples of community pandemic responses. Our interviewees were rightly proud of their achievements. However, it is important to note that as a Bangkok-based organisation reaching out to rural communities through its local partners, there were unavoidable expectations that may have conditioned the responses to a degree. These expectations were evident in the question posed to us at the end of two of the interviews: In what ways might we be able to provide additional support to them?

It is important that grassroots experiences are not excluded from narratives around the pandemic. This blog post has explored how some of Thailand’s most marginalised and peripheral populations dealt with the pandemic during the country’s first wave. Although very preliminary, these observations provide a snapshot of the diverse modes of grassroots governance that operate alongside and, to greater or lesser degrees, either independently of or in tandem with formal structures of local government. It finds that under the right conditions, communities can manage themselves with the minimum of government guidance and support. These findings also help to challenge the conventional understanding that is held by members of Bangkok’s urban elite that tends towards a more disempowering view of rural communities, particularly those ethnically Malay-Muslims residing in the country’s conflict affected borderlands.

References

Fumio Nagai, “Central-Local Government Relationship in Thailand,” Joint Research Program Series. Japan External Trade Organisation: Institute of Developing Economies. March 2008. https://www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Reports/Jrp/147.html.

The author would like to express a special thanks to colleagues Koneetah Saree and Anchalee Madliad to acknowledge their contributions and efforts in coordinating with the communities.

*The cover image is by Ameeroh Lebesa who retains copyright.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.