“The new hierarchy of mobility deservingness raises political and ethical questions that should be carefully thought through, critiqued and debated”, writes Dr Sin Yee Koh (Senior Lecturer in Global Studies at Monash University Malaysia)

_______________________________________________

Borders and bordering practices have long been used by nation-states to selectively include and exclude migrants and foreigners, whether in-territory or ex-territory. This has been no different in the era of the Covid-19 pandemic. On the one hand, travel lockdowns have thickened existing external borders, preventing inward and outward mobilities. Under the guise of health security, additional layers of internal and external borders have emerged. This accentuates and complicates existing structures that stratify the already selective inclusion and exclusion of “others”. On the other hand, in juggling pandemic control and economic recovery, some countries have introduced new bordering tactics such as travel bubbles, green lanes and fast lanes to spur the mobilities of those whom are considered eligible.

These new and emergent borders and bordering tactics are being used by state authorities in an attempt to manage and control the spread of the virus and its other implications. However, underlying these tactics are certain logics and assumptions about who should be protected, who should be kept away, and who should be allowed in/out, when and where (Ferhani & Rushton, 2020; Laocharoenwong, 2020). In this reflection piece, I put forth a twofold argument: first, the Covid-19 pandemic has shed light on the enduring logics of injustice that inform existing and emergent borders and bordering tactics; and second, as health security becomes intertwined with the governance of mobilities, we will be seeing the emergence of new hierarchies of mobility deservingness that have important political and ethical implications.

Borders: From lines to time-specific spaces

When thinking of borders, it might be easy to jump straight into using linear metaphors – lines that demarcate, walls that segregate, boundaries that include/exclude, partitions that divide, or gates that open/close. Regardless of which metaphors we use (see Palmer, 2020, pp. 177-179), the important thing about borders is that they perform these functions selectively. The criteria – for inclusion/exclusion, entry/non-entry, permission/restriction – are typically based on selective sets of requirements. Furthermore, these sets of selective criteria may vary across contexts and in time.

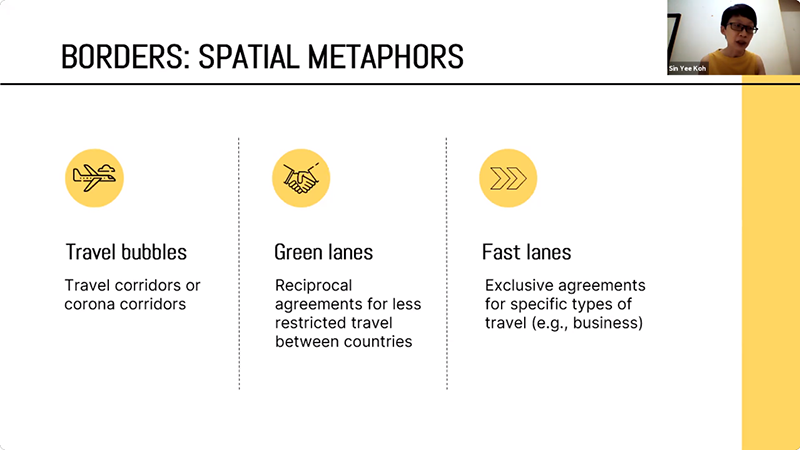

Of course, none of this is new: borders and bordering tactics have been in use for a long time, for different purposes – whether to selectively include/exclude certain groups or to produce certain (economic/political) subjects (Mezzadra & Neilson, 2013; Newman, 2016). However, the Covid-19 pandemic has given us more concrete examples of borders as spaces, in contrast to lines. For example, we see the emergence of “travel bubbles”, also known as “travel corridors” and “corona corridors”, that are a kind of protected zone of travel – almost like a tunnel. These corridors are theoretically sealed from the original point to the destination point, as well as throughout the journey. We also see the emergence of “green lanes”, “fast lanes” and “fast-track entry” for less restricted travel, depending on bilateral or other agreements.

What is interesting here is that the border becomes a space tied to a specific temporality. The bubbles and corridors exist only in a specific spatio-temporality, created upon the mutual agreements of the authorities involved. As people travel in and through these border(ed) spaces, their mobilities are circumscribed and characterised by different velocities and viscosities. On the one hand, some get to move from point A to point B with faster speeds, lesser hassles, and lesser additional costs – whether these are financial or opportunity costs. On the other hand, some mobilities are significantly slowed down, are subject to multiple starts and stops along the way, become suspended, or even entirely prohibited. In sum, as borders morph into time-specific spaces, travel, migration and mobility have also been significantly changed.

Shifting borders: Enduring injustices and new hierarchies of mobility deservingness

To understand borders and bordering tactics during the Covid-19 era, I turn to Ayelet Shachar’s (2020b) The Shifting Border. Shachar argues that the border “has become a moving barrier, an unmoored legal construct” (p. 4) that is not fixed in place. Indeed, as the border becomes disentangled from a fixed locality, it attains spatial agility. Nevertheless – and perhaps because of this unfixed nature – the shifting border can be flexibly used to suit different purposes at different times. In this sense, the border becomes a method (Mezzadra & Neilson, 2013), a means to creatively and flexibly operationalise inclusion and/or exclusion as and when necessary.

In the context of pandemic control, the shifting border offers nation-states the ability to contain or keep out those who are deemed risky, in order to protect those who are deemed worthy of protection. However, Ann Stoler (2016, p. 121) has highlighted that “what and who must be kept out and what and who must stay in are neither fixed nor easy to assess. Internal enemies are potential and everywhere.” Similarly, there is no clear and universal answer to the question of “who gets in, …[who] gets out, and who gets rescued” (Ferhani & Rushton, 2020, pp. 461-462, original emphasis). During the pandemic, we see this fear of the potential enemy being manifested in increased health and mobility surveillance, lockdowns that result in selective im/mobilities, and deportations.

It is here that the Covid-19 pandemic exposes the enduring injustices, based on existing structures of inequalities such as race and class that are, and have been, unequally shouldered by different groups. Those who have been marginalised in pre-Covid-19 times (e.g., migrant workers, asylum seekers) are easily and uncritically turned into “enemies”. They are contained, detained, fixed in place, kept waiting, stopped in their tracks, deported. By contrast, those who are not seen as enemies are allowed to move, to cross internal and external borders – because they are not seen as a (health) security threat.

Regardless of the rationale behind it (which include legitimate public health considerations), the shifting border translate into material violence that position people into “new relations of power in political spaces of im/mobility” (Shachar, 2020b, p. 6; see also Shachar, 2020a). As health security becomes intertwined with the governance of mobilities, I argue that we will be seeing the emergence of new hierarchies of mobility deservingness (cf. Ormond & Nah, 2020, “hierarchies of healthcare deservingness”). Those who are deemed fit for travel – i.e., deserving of (risk-free) mobility – are allowed to move. As a result, they will be able to access and accumulate mobility capital which can be converted into other forms of capital in the future. This, in turn, contributes to the exacerbation of inequalities as this new structure of inequity – mobility deservingness – overlaps onto and interacts with existing ones (e.g., race, class, citizenship, etc.).

Concluding thoughts

In moments of crisis, great uncertainties, or a pivotal moment in history – like the current Covid-19 pandemic – we can observe that states display a tendency to deepen the “highly variegated terrain of social protection and vulnerability” (Sheller, 2018, p. xi). Protection becomes selective, while non-protection or outright abandonment expands to more groups and individuals. This clearly signals and reminds us that rights and privileges are discretionary (Koh, 2020). One’s status and one’s access to rights and privileges are subject to changing circumstances and shifting state priorities (Shachar, 2020a). They are not – and cannot – be taken for granted. This applies equally to those of us who belong to groups of relative privilege (e.g. citizens, permanent residents, privileged migrants), as well as those of us who belong to groups of relative underprivilege (e.g. undocumented migrants). This is because, as borders shift, morph and mutate, we come to be positioned into these categories, sometimes without us even realising.

The development of new hierarchies of mobility deservingness is important, because we know that migration and mobility are ways for people to achieve their aspirations, to have a chance at attaining social mobility, or to escape vulnerabilities. Furthermore, mobility has implications for residential status and citizenship acquisition later on, or for the next generations. This is therefore not just a question of equity and justice of the current generation; it is also about that of future generations. The new hierarchy of mobility deservingness raises political and ethical questions that should be carefully thought through, critiqued and debated.

References

Ferhani, A., & Rushton, R. (2020). The International Health Regulations, COVID-19, and bordering practices: Who gets in, what gets out, and who gets rescued? Contemporary Security Policy, 41(3), 458-477.

Koh, S. Y. (2020). Noncitizens’ rights: Moving beyond migrants’ rights. Migration and Society, 3(1), 233–237.

Laocharoenwong , J. (2020, October 9). COVID-19, health borders, and the purity of the Thai nation. Heinrich Böll Stiftung.

Mezzadra, S., & Neilson, B. (2013). Border as method, or, the multiplication of labor. Duke University Press.

Newman, D. (2006). The lines that continue to separate us: Borders in our ‘borderless’ world. Progress in Human Geography, 30(2), 143-161.

Ormond, M., & Nah, A. M. (2020). Risk entrepreneurship and the construction of healthcare deservingness for ‘desirable’, ‘acceptable’ and ‘disposable’ migrants in Malaysia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(20), 4282-4302.

Parmar, A. (2020). Borders as mirrors: Racial hierarchies and policing migration. Critical Criminology, 28(2), 175–192.

Shachar, A. (2020a). Beyond open and closed borders: The grand transformation of citizenship. Jurisprudence, 11(1), 1–27.

Shachar, A. (2020b). The shifting border: Legal cartographies of migration and mobility. Manchester University Press.

Sheller, M. (2018). Mobility justice: The politics of movement in the age of extremes. Verso.

Stoler, A. L. (2016). Duress: Imperial durabilities in our times. Duke University Press.

* This post is based on Dr Sin Yee Koh’s roundtable intervention delivered on 27th October 2020 as part of SEAC Southeast Asia Week 2020. You can access a recording of the “Migration and Mobility in the COVID-19 Era” roundtable here.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

1 Comments