Children are turning to social media platforms, like Instagram, TikTok or Twitter, to voice their political views and express their activism. What does this tell us about children’s media use and justice? For www.parenting.digital, John Hartley discusses his recent paper in the LSE’s Working Papers series. He applies to ‘children of media’ a general model of culture’s function, using a systems and evolutionary perspective (developed here, here, and here) to argue that ‘class consciousness’ is being formed around ‘the means of mediation’ and children use a range of social-media affordances to challenge existing political and intellectual order.

Children are turning to social media platforms, like Instagram, TikTok or Twitter, to voice their political views and express their activism. What does this tell us about children’s media use and justice? For www.parenting.digital, John Hartley discusses his recent paper in the LSE’s Working Papers series. He applies to ‘children of media’ a general model of culture’s function, using a systems and evolutionary perspective (developed here, here, and here) to argue that ‘class consciousness’ is being formed around ‘the means of mediation’ and children use a range of social-media affordances to challenge existing political and intellectual order.

Children as a whole are engaged in what I call ‘worldbuilding’, following designer Alex McDowell. In the past, all cultures, languages and semiotic systems have created boundaries between ‘us’ and ‘them’, sometimes policed, sometimes porous. But today’s children of media are the first to be born into a ‘deme’ (an inter-knowing group) that knows from the start that ‘we’ are ‘one species; one planet’.

For such a group, where is the boundary between ‘us’ and ‘them’? Increasingly, it is drawn between humanity and the planet as a whole. Faced with insistent evidence of climate change, environmental degradation, mass extinctions, pollution, waste, monoculture – and with equally insistent institutional resistance to dealing with it – children of media are forming themselves into a ‘world class’ – the first of that name – in opposition to humanity’s own collective agency. In other words, ‘we’ are our own worst enemy, the emerging Anthropocene era is our responsibility, and children are necessarily the agents of future action.

Children construct their own demes within which to achieve a sense of self, even as they face uncertainties not already coded (which we call ‘the future’). The performance of this systemic function is, just as Philip Pullman describes in His Dark Materials, which requires Lyra Silvertongue to act in ignorance of what she is doing, because ‘If told what she must do, she will fail’. The same applies to all children in relation to their cultural practices. Their semiotic action unwittingly creates new groups for any and all cultures.

In the process, they come to recognise their deme through shared knowledge – sometimes encyclopaedic, sometimes arcane, always bounded by a strong sense of distinction from those who are not ‘we’-group insiders. Recognising such peers affords children informal signals for navigating risk, but equally, because any ‘we’ implies a ‘they’ (and moral or political valuations ensue), this requires intersectional initiatives for countering involuntary racism.

A global ‘class’ is not formed around the means of production, as Marxist classes were. Instead, given that the only ‘means’ of planetary extent are computational and connective digital and social media, this class is being formed around ‘the means of mediation’. In some cases, it is led by girls, like Greta Thunberg. Fewer may have come across her peers in different countries, but here they are, ready to put the demands of their class for climate justice to world leaders (Fig. 1).

meeting Angela Merkel for talks on climate change (August 20, 2020). Source: Instagram.

Now that these pioneers, and others like Malala Yousafzai, are ‘graduating’ from childhood, the baton of leadership passes to many new hands across the world. Here is where a further characteristic of children as a ‘class for itself’ can be identified. Although there are necessarily prominent and specialised leadership cadres on the Thunberg model, it is important to notice that ‘class consciousness’ is widespread among children across the range of social-media affordances.

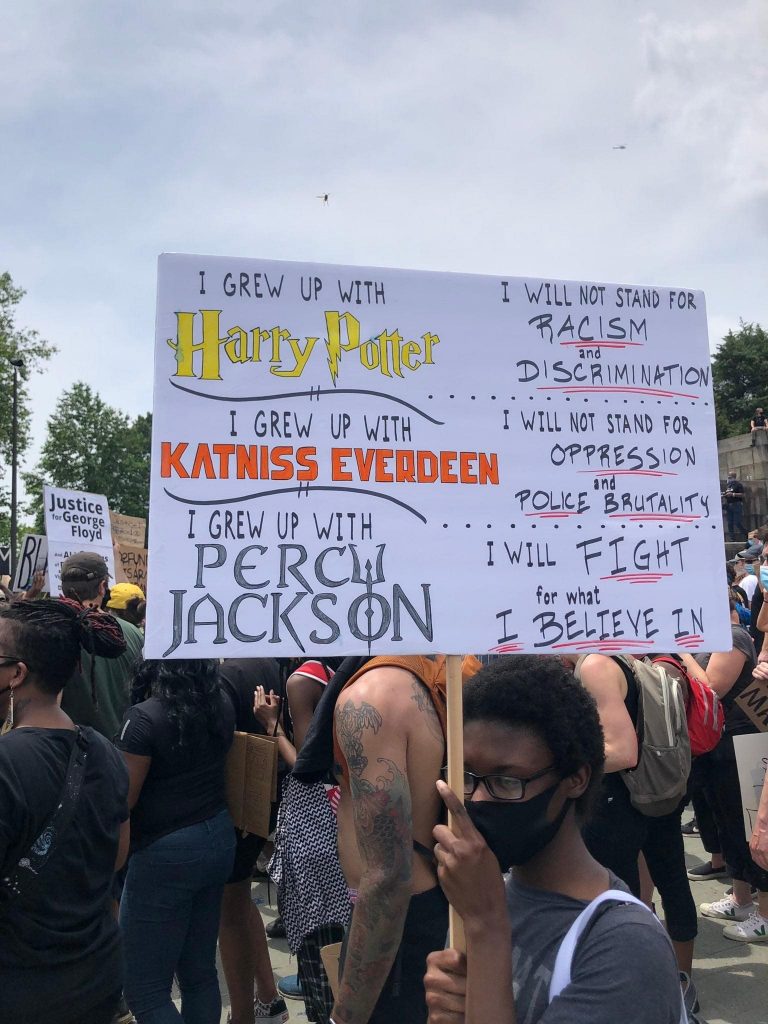

Those who have achieved prominence as celebrities and influencers, for instance via dance videos or some other popular craze, have proven ready to step up to ‘political’ duties in relation to child-centric problems like cyberbullying, body-shaming and cruelty. They are equally open to causes like Black Lives Matter (Fig. 2), Fridays for Future, and School Strike for Climate (Fig. 3). In other words, ‘deme-forming’ platforms like TikTok are ablaze with activism, advocacy, and tutorials about environmental issues, while children – and their allies – take to the streets.

The means of mediation

Human culture is founded on language, deployed via media – speech, song, story and stone, all the way through to print and electronic media, from broadcasting to the internet. All media outlets – from stone circles to TikTok – ensure the dissemination of knowledge among and across groups. What’s changed in recent years is not so much children (although childhood seems to get longer and less purposeful as affluence turns youngsters into a leisure class); it’s the media that have rapidly evolved.

Where communication technologies used to be monopolised by priests and monarchs, or belong to industrial enterprises, they are now integrated into the continuing immediacy of everyday life across the planet, putting global communication into the hands of whole populations, not just firms and state institutions. Children don’t treat social media as media but as part of a personal-relational connective repertoire. The corporate platforms they use are no more theirs than language is, of course, but they have their own imperatives on their minds.

The whole cultural universe is what Juri Lotman calls ‘the semiosphere’, operating at a global scale in all languages and media. Particular cultures, languages or persons create and occupy multiple subsystems, from local ‘small-world’ social networks to far-flung empires, religions, fandoms etc. But the abstract process is the same at any scale: culture makes groups, groups make knowledge. Interacting groups make new knowledge, as they adapt or succumb to change and out of these dynamic relations are precipitated senses of self, or what we call individuals.

Justice?

‘Children of media’ pose a serious challenge not only to the legitimacy of political leaderships but also to the intellectual hegemony of the behavioural sciences that currently dominate studies of children. How to admit children’s own class consciousness and political activism into formal knowledge? How can intersectional cooperation between children and the sciences, at species scale, be built in time to allow them to enjoy the planet after ‘we’ have finished with it?

First published at www.parenting.digital, this post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

You are free to republish the text of this article under Creative Commons licence crediting www.parenting.digital and the author of the piece. Please note that images are not included in this blanket licence.

Featured image: photo by Markus Spiske on Pexels