This post considers some of the findings from our latest book Parenting for a Digital Future which explores how parents imagine the future for their children, including the role of digital technology. Based on in-depth interviews of British parents, educators and children, we asked how parents are tackling the challenges of the digital media landscape. Sonia Livingstone is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: C. Robillard, CC BY-NC 2.0]

This post considers some of the findings from our latest book Parenting for a Digital Future which explores how parents imagine the future for their children, including the role of digital technology. Based on in-depth interviews of British parents, educators and children, we asked how parents are tackling the challenges of the digital media landscape. Sonia Livingstone is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project. [Header image credit: C. Robillard, CC BY-NC 2.0]

For our book, Parenting for a Digital Future, we surveyed some 2,000 UK parents, finding that they are broadly optimistic about their child’s future: 86% of UK parents are fairly or very confident of their child’s health, 82% of their learning, 80% of their friendships, 79% of their safety, and 76% of their future. Yet such optimism is often tempered when it comes to technological changes and the societal pressures faced by children.

What role do parents think that digital technology plays?

Parents are ambivalent about technology. Nearly all (88%), believe that “It’s important for my child’s future that they understand how to use technology.” But half also think that society should worry about technological change, with only one third disagreeing.

They are sceptical that “children today will grow up to do jobs that haven’t been invented yet” (42% agreed), or that “children get the knowledge they need for the future outside of school” (32%) rather than in school. But only 13% think that “predictions about how fast society is changing are generally exaggerated.”

When asked to weigh the benefits against the harms for their child, the scales are just tipped in favour of the benefits – with parents especially valuing the role of technology in supporting school learning, pursuing hobbies and interests, being creative and expressive, and preparing for future work. They are more doubtful, but still not negative overall, about possible benefits to their child in their developing relationships with family or friends, or learning social and emotional skills.

And they are evenly divided on whether “digital media like smartphones and tablet devices make parenting harder.”

Of course there are differences among parents:

- Mothers are more likely to value the learning benefits of technology;

- Older parents are a little more positive than younger parents about the value of their children learning skills when using technology;

- Younger parents value more the potential of technology for relationships and social/emotional learning;

- Parents of teenagers especially think that technology will help prepare them for work in the future.

What about how they are doing as a parent themselves?

The survey asked parents if they “feel I am doing a good job as a parent” – 29% strongly agreed and a further 55% agreed, with little variation by socio-economic status, ethnicity or child age. This leaves little support for popular claims that parents are incredibly anxious or lacking in confidence. Instead, over half said “I believe I can influence the kind of person my child grows up to be” (59%).

However, middle class parents feel more supported by friends and family, and say they have more sources of information and advice available to them.

How have things changed from one generation to the next?

We asked parents, “When you think of your own childhood, do you think your child has more or less freedom to do what they want?” Half think they had more freedom, 30% about the same and one fifth thought they had less freedom.

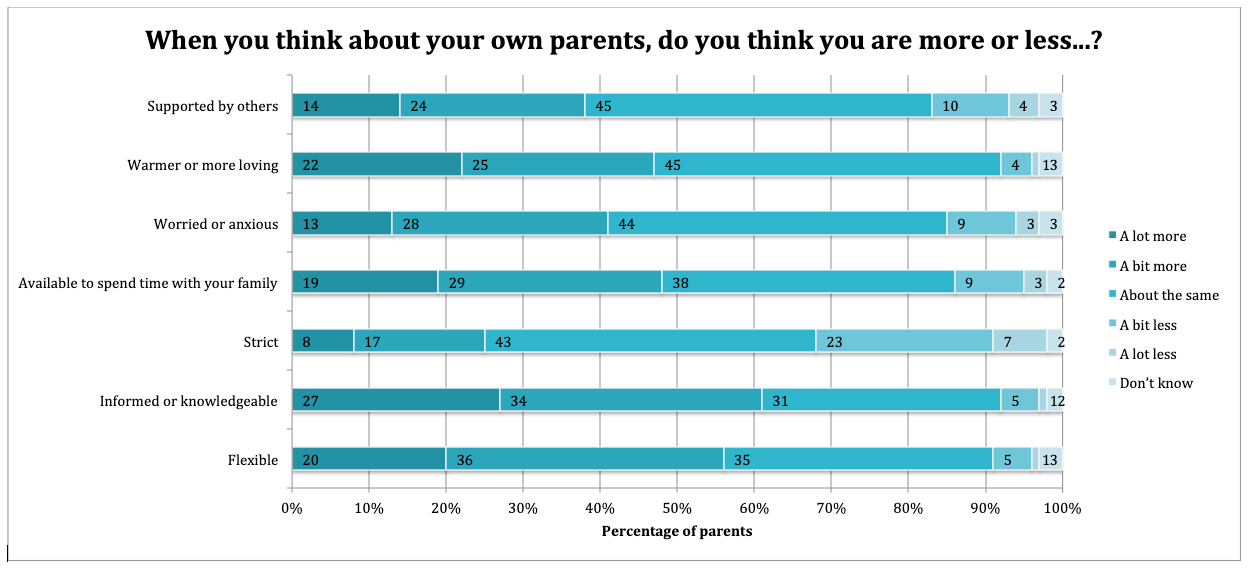

We also asked them, “when you think about your own parents, do you think as a parent that you are more or less flexible?” Half answered a bit or a lot more, one third about the same. In answer to similar questions comparing themselves with their own parents (see graph below):

- Around half also think they are more “informed or knowledgeable” and “available to spend time with your family”, with one third again saying “about the same”;

- Parents think they are less strict as parents, and more worried or anxious, on average – interestingly with few differences by socio-economic status;

- As for “warmer or more loving”, half think they are more so, half about the same;

- And they tend to think they are a bit more supported by others than their parents had been.

How do they regard their child’s future?

Here again parents’ broad optimism is tempered by ambivalence:

- 70% said their child had a bit or a lot more opportunities than they did as a child;

- But two thirds (63%) also said that today children are subject to greater pressures from society than they had to face when they were children;

- Indeed, 54% think that “children are under too much pressure these days;”

- On whether their child’s chances for financial and professional stability are greater that those they had enjoyed, 44% think they are better, 36% think them about the same, and one in five think them worse;

- We asked parents to compare their child’s opportunities for a good quality of life compared with their own: again, parents are fairly optimistic – half think their child’s opportunities better, one third think them about the same.

We’re delving further into these beliefs in our new book. We’re particularly interested in the ways in which parents’ various beliefs about the future, and the digital, influence how they parent their child in the here-and-now. As you may guess from the above, although we’re fascinated with how technology is preoccupying parents – a lively focus of conversation, and sometimes conflict – we will not be agreeing with those commentators who see parents as a homogenous group tormented by anxiety or panicked about technology.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.