While children in Norway are often referred to as ‘digital natives’, new research by EU Kids Online suggests that this is an inappropriate term. It discovered that although children often understand concepts related to the internet, they can’t always apply the practical skills related to those concepts. The findings suggest that children may need more support online. Niamh Ní Bhroin is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo. Niamh is a member of the Norwegian EU Kids Online team. Her research explores Nordic children and media use, media innovation, digital literacy and privacy.

While children in Norway are often referred to as ‘digital natives’, new research by EU Kids Online suggests that this is an inappropriate term. It discovered that although children often understand concepts related to the internet, they can’t always apply the practical skills related to those concepts. The findings suggest that children may need more support online. Niamh Ní Bhroin is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Media and Communication, University of Oslo. Niamh is a member of the Norwegian EU Kids Online team. Her research explores Nordic children and media use, media innovation, digital literacy and privacy.

Norwegian children and internet use

Children who grow up with the internet and mobile media are often considered to be ‘digital natives’. In Norway, 92% of children from the age of nine own a mobile phone and most children access the internet daily, often from a range of different devices. However, building on an increasing body of research undertaken by the EU Kids Online network, we find that while children both own and use devices that are connected to the internet, they are not born with the competences and skills they require in order to live good lives with these technologies. Just as with other aspects of life, children learn through a combination of practical experience and guidance how to live and thrive in digitally mediated contexts.

The Norwegian EU Kids Online team is currently implementing a nationally representative survey to investigate children’s online opportunities, risks and safety. Nordic children have been categorised as ‘independent’ and ‘sophisticated’ internet users. At the same time, Norwegian parents worry about the amount of time their children spend online, and the kind of content, or people, they may encounter there.

In preparation for this national survey, we undertook a qualitative study to explore how children understand the internet. We found that while children understand key concepts that relate to the internet and digital media, they do not always possess the practical skills that these concepts refer to. Furthermore, while children are interested in protecting their privacy, and are occasionally quite adept at doing so, they are not always aware of when their privacy might be compromised.

Our study was inspired by research conducted in the Czech Republic in 2017 which found that conceptual understandings of technologies and experiences related to the internet had evolved since the previous round of data collection in the Czech Republic in 2009. Some of the children interviewed didn’t understand concepts like ‘chat room’, ‘social media’, and ‘blog’. Being mindful of the findings of this research, we wanted to explore how children in Norway understood the internet in 2018.

Our Study

We visited three schools and one regional science museum in Norway between 1 March and 6 April 2018 and conducted semi-structured interviews and observation with children aged between 9 and 15. In total we observed 235 children, and interviewed 141, during 30 hours of instruction.

The difference between concepts and skills

The children were familiar with many concepts relating to internet use. However, there was a disconnection between their familiarity with these concepts and their ability to use the practical skills that the concepts referred to. For example, the children understood what a password was but they struggled to remember their passwords and to use them to access different devices and applications.

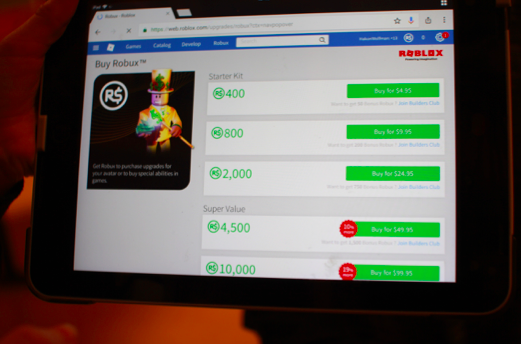

Furthermore, while the children were used to interacting with commercial content, both on YouTube and via their Gmail accounts, they were not entirely clear what we meant when we asked them about ‘in-app purchases’, or ‘pop up’ advertisements. This reinforces the need to challenge the application of the ‘digital natives’ label to children. It also raises concerns about the practical skills that children might lack when using the internet.

Protecting Privacy

When we spoke to children about the appropriateness of different actions online, they often referred to what they thought their parents and teachers would allow them to do. Their understandings were also quite context specific. For example, the children knew that they should probably not send a photo of themselves to a stranger online. In spite of this, some children did not consider it problematic to upload videos of themselves to social media platforms, such as TikTok. This reconfirms how difficult it can be for children to protect their privacy, particularly in contexts where they are interacting with friends on social media platforms, and reinforces the conceptualisation of children as naïve experts.

Permissions and restrictions

The children also understood that their use of the internet was regulated by a range of permissions and restrictions, and that these could vary according to where they were, i.e. at school, at home, or visiting with friends. Most of the children used YouTube to watch music videos and short films. However, very few children had uploaded content to YouTube. Some of the younger children thought that their parents or teachers would not allow them to do this.

However, permissions and restrictions were also interpreted by the children in different ways. We observed for example that YouTube was used by some of the children to access content that was otherwise restricted. These children used YouTube to watch films of gamers playing ‘Fortnite’, a game they otherwise were not allowed to play.

Complicating understandings of how internet use is regulated, some of the children were aware that their online interactions could be monitored. During one interview we were told that the teachers at a school could track everything that the children watched on YouTube when using the iPads issued by the school. This kind of monitoring was considered problematic. Our research therefore again confirms that children and young people care about their privacy when using the internet.

Conclusion

The main dilemma this research presents is the disconnection between the children’s familiarity with a range of internet-related concepts, and their possession of the practical skills these concepts refer to. We cannot take it for granted that children who might understand what a password is can in fact both access and protect their internet accounts. Furthermore, while children care about their privacy and understand how to manage this in certain contexts, we cannot take it for granted that this means that they will not compromise their privacy when using the internet.

Norwegian children spend a considerable amount of time online, and both own and use a range of digital media devices. However, we consider it more appropriate to refer to these children as ‘naïve experts’ rather than ‘digital natives’. This allows us to begin to explore the range of supports that children need, and can access, in order to live good lives with digital media. One point of departure would be to explore who children see as relevant sources of guidance (for example their parents, teachers, siblings and friends), and how these individuals can provide varying kinds of support as children engage with the internet.

Notes

Both the 2018 EU Kids Online survey in Norway, and this qualitative investigation, have been funded by the Ministry of Justice and Public Security, in part-fulfilment of their strategy for the prevention of violence in close relations. The full report arising from the study can be accessed here.

This post gives the views of the authors and does not represent the position of the LSE Parenting for a Digital Future blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.