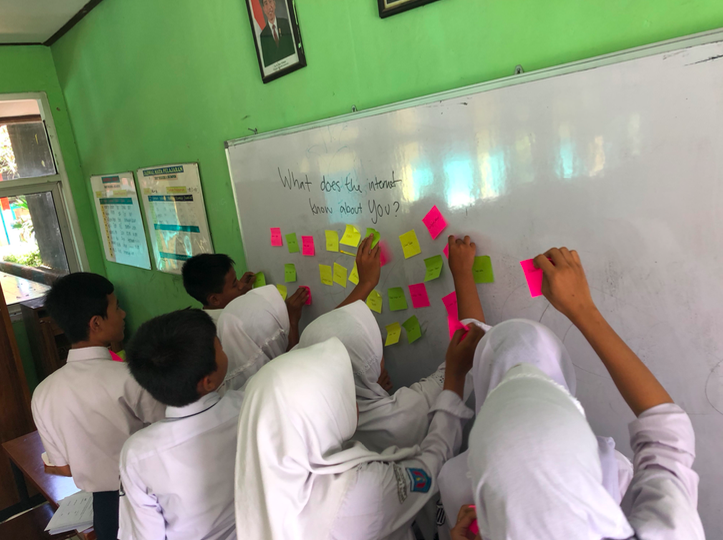

Recent research by Project Open Eyes in Lagos, Nigeria has found that while nine out of 10 teenagers have access to the internet and three out of four have made friends with strangers online, there remains a very low level of digital literacy and a lack of regulatory protection at the state level. In this post Chukwuemeka Monyei calls for a more sustained effort by the government to improve digital literacy initiatives and increase funding for ICT education, equipment and infrastructure. Chukwuemeka is the co-founder of Project Open Eyes, a social project which aims to promote a sustained, inclusive campaign about children and media. He is a practicing lawyer and adjunct lecturer at the Lagos Campus of the Nigerian Law School where he teaches Corporate Law practice. [Header image credit: Richard Stupart]

Recent research by Project Open Eyes in Lagos, Nigeria has found that while nine out of 10 teenagers have access to the internet and three out of four have made friends with strangers online, there remains a very low level of digital literacy and a lack of regulatory protection at the state level. In this post Chukwuemeka Monyei calls for a more sustained effort by the government to improve digital literacy initiatives and increase funding for ICT education, equipment and infrastructure. Chukwuemeka is the co-founder of Project Open Eyes, a social project which aims to promote a sustained, inclusive campaign about children and media. He is a practicing lawyer and adjunct lecturer at the Lagos Campus of the Nigerian Law School where he teaches Corporate Law practice. [Header image credit: Richard Stupart]

Project Open Eyes (POE) is the online safety initiative of Like a Palm Tree Foundation, a Nigerian not-for-profit that focuses on children. This post looks at the results of 2,041 interviews with children in Lagos, Nigeria, between the ages of 12 and 17 conducted by POE. The surveys were carried out using paper-based questionnaires that sought to understand the social media/chat sites children had joined, the ownership of the devices with which they went online and the experiences they had online – content, conduct and contact-wise. The results showed high use of the internet for academic purposes, socialisation and entertainment. It also revealed that they are engaged in sexting, online dating and viewing of pornography, to varying degrees.

An overlooked problem

In spite of increasing traction in the area of digital literacy, very little attention is being paid in Nigeria to the issue of digital safety for children. This is in spite of the fact that the country has gained a level of notoriety for young people committing online fraud, and for children being harmed by strangers they have met online. In 2012, news of the death of Cynthia Osokogu hit the headlines. Cynthia, who was only 24 at the time of her death, was murdered on a trip to Lagos, which she had been invited on by young men she had met on BlackBerry Messenger and Facebook.

However, Cynthia’s decision to become acquainted with strangers online is not peculiar to her. In our survey three out of four of the respondents said they have strangers as friends online. At least three in every five girls surveyed said that they have been contacted by a male stranger online. Three out of five of those who have been contacted said that they replied to strangers to see what they had to say before they decided what to do.

In the course of carrying out our research, we have come across several stories of physical and psychological harm that young persons have encountered both online and offline (particularly cyber-bullying and online grooming). Many of these stories never make the news.

How are parents tackling online risks?

Pornography and online grooming are issues that many parents see as major risks to children online and they have reason to do so. Nine out of 10 of the teenagers in the survey own a smartphone or mobile that can be used to access the internet. Seven out of every 10 of the boys have come across pornography online and five out of every 10 have intentionally accessed it, while six out of 10 girls have come across pornography online and nearly three out of 10 of the girls have intentionally accessed it.

Fifty-four per cent of the girls say that someone has attempted to have a sexually explicit conversation with them online while 25 per cent of the girls say that someone has asked for a nude or semi-nude picture of them online. Seven per cent of these girls acceded to such requests.

But such a problem is not unique to Nigeria. Nearly every young person and parent interviewed in this video by the Global Kids Online project lists pornography as one of the negatives on the internet which young persons encounter.

Preliminary results from an ongoing survey of parents that we are conducting shows that more parents have spoken to their children about pornography than online dating (potentially an initial phase of online grooming). To combat pornography and other risks, many parents are placing restrictions on their child’s internet access. At least one in four of the teenagers that participated in the survey we conducted in Lagos said that their parents placed some form of restriction on their internet use such as time spent and content accessed online.

However, these parents appear to be in the minority. We held a sensitisation workshop for parents on online safety in Lagos to enlighten them about the risks children face and what they can do about it. One father came because he wanted to be assured that it was not only his wife and himself that were setting strict rules for their son’s online use. The forum also allowed parents to share their experiences and learn from one another.

Parents can also draw wisdom from the trove of open source online materials that address online safety of children. That way, they can learn about and stay updated on child online safety issues globally and see how it may affect their children.

The case for government intervention

Despite global traction, there is still no international treaty or agency for cybersecurity/digital rights of all individuals or specifically for children. However, many states have set up frameworks to protect children in their jurisdiction who go online.

This is yet to happen in Nigeria. Governmental response to increasing internet usage has been slow. Not just as it pertains to children, but generally. For example, the specific law in Nigeria that deals with cybercrimes was only passed into law in 2015. The Child’s Rights Act 2003 – the national law that domesticates the Convention on the Rights of the Child – has only been domesticated in 24 out of the 36 states in the country. In many states where the law has been passed, its implementation is abysmal.

With Nigeria’s literacy rate at 59.6 per cent, it is unsurprising that the country has a low rate of digital literacy. In the African Digitalisation Maturity Report 2017 by Siemens and Deloitte, Nigeria was found to have a score of 18 for the digital literacy pillar of the study (the lowest of four African countries studied – the others were South Africa, Kenya and Ethiopia). At the moment, there are no known figures for smartphone use and access among children in Nigeria, unlike what is available for some other African countries.

It is not all gloomy

There are moves by government bodies at various levels in Nigeria to promote digital literacy, and in turn, better educational opportunities for many young persons. For example, there is the Opon Imo project, launched in one of the states under which students in government-owned secondary schools receive free tablets pre-installed with educational resources.

There is also a very strong push in the private sector to promote digital literacy. Tech companies, social entrepreneurs and not-for-profits are all engaged in projects to increase digital literacy. For example, the Co-Creation Hub, an innovation centre based in Lagos and Abuja, runs an annual programme to teach kids basic coding skills with the goal of reaching one million students in five years. Also, earlier this year, the Federal Ministry of Education approved the Cisco Networking Academy Programme, a CSR initiative for the provision of quality ICT education across federal government-owned schools.

A lot of opportunities exist for children who have access to the internet and are literate enough to know how to use its resources, and it is good that the private sector is taking initiative; however, government at all levels will have to do more to fund education generally and ICT education specifically. Improved infrastructure in public schools is highly anticipated and this should be accompanied by plans for well-equipped ICT labs and attendant teachers.

As is often the case, attention to the issue of digital literacy will provide an opportunity to educate about digital safety.