Though the Bolsonaro government’s approach to land-use and the environment has intensified damage to Brazil’s crucial biological communities, a growing fightback is also laying the foundations for climate change litigation that could be vital for Brazil and the wider world, write Joana Setzer (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, LSE), Caio Borges (Institute for Climate and Society), and Guilherme Leal (Graça Couto Advogados).

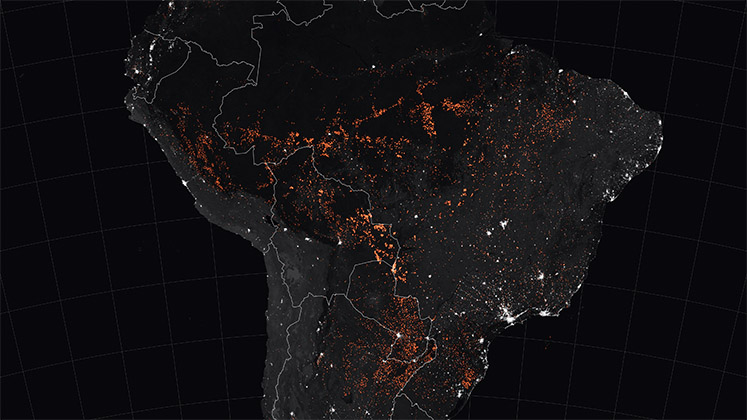

Brazil is in the middle of an environmental crisis, and one that has only gotten worse since President Jair Bolsonaro took office in January 2019. The intensification of forest fires in the Amazon has led to significant national and international debate; deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon is rising sharply, with the total area destroyed higher in 2019 than in any year since 2008 and an annual growth rate (34%) not seen since 1995; and a recent report shows that Brazil’s carbon emissions increased by 9.6% in 2019, mainly due to rising deforestation during the first year of the Bolsonaro administration.

Protecting the Amazon in Brazil

There are two key issues at the core of this environmental crisis.

First, Brazil plays host to a number of peculiar biological communities that have formed in response to shared physical climates, otherwise known as biomes: the Amazon, the Cerrado tropical savannah, the Pantanal wetlands, and the Atlantic rainforest. Together they represent the largest expanse of tropical biomes in the world, providing an incredible degree of biodiversity and playing a crucial role in regulating weather and climate patterns.

Second, under the current administration the state has increasingly neglected its role as a supervisor and enforcer of environmental policies. Instead, the government has proposed or supported various pieces of legislation that aim to provide an amnesty for illegal activities relating to land-use. More generally, climate policies and institutions have been dismantled, environmental science questioned, and civil society threatened.

However, these difficulties are also fuelling a fightback from public prosecutors, civil society organisations, and political parties. So much so, in fact, that the legal actions they have initiated – sometimes jointly – may even be solidifying the legal and institutional foundations of future climate change litigation in Brazil.

Public prosecutors and climate change litigation in Brazil

Public prosecutors, both state and federal, enjoy a high degree of autonomy in Brazil. The Prosecutor’s Office, which carries out criminal proceedings relating to state assets and companies, is technically independent, falling outside the remit of the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of government. Public prosecutors have the prerogative to investigate and prosecute cases that protect collective and diffuse rights like children’s rights or consumers’ rights, as well as those relating to the environment.

In 2018, the federal prosecutor’s office set up a special taskforce to curb the illegal and criminal activities driving deforestation in the ten states that make up the Legal Amazon. More recently, this taskforce started to focus on the climate change implications of the dismantling of anti-deforestation policies. In April 2020, the taskforce filed a court injunction alleging that the federal government is failing to contain an unprecedented surge in deforestation in ten particular hotspots. They argued that the government is setting the country up to miss the climate targets established in the national Climate Law and the Brazilian nationally determined contribution submitted to the 2015 Paris Agreement, which includes a commitment to reduce the annual rate of deforestation by 80%.

The first ruling by the lower court invoked the precautionary principle and the principle of non-regression in environmental law to order the defendants to submit a plan of action that would halt the surge in illegal deforestation and ensure that indigenous and traditional communities are not exposed to COVID-19. This ruling was later overturned by the Court of Appeal, however, which privileged the separation of powers and the autonomy of environmental bodies in deploying scarce resources for environmental inspection operations, especially in the context of an unprecedented global pandemic.

NGOs and climate change litigation in Brazil

In recent years, a number of human rights and environmental NGOs have also begun to organise events and publish studies about strategic climate change litigation. In 2020, the first cases were finally filed.

The first climate lawsuit, brought in June 2020, was filed by the NGOs Greenpeace Brazil and Instituto Socioambiental after being developed in collaboration with Brazil’s Environmental Prosecutors Association (Abrampa). It sought to overturn a measure by the federal environmental agency that relaxed regulations on timber exports. The suit argued that this measure jeopardises the integrity of the Amazon biome, which is already perilously close to turning irreversibly into a savannah.

In October 2020, the NGO Instituto de Estudos Amazonicos filed another climate case against the government, this time focusing squarely on illegal deforestation as Brazil’s main source of greenhouse gas emissions. The plaintiff aims to ensure that the Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (PPCDAm) is brought into line with the National Policy on Climate Change, which guarantees a maximum rate of illegal deforestation in the Legal Amazon of 3,925 square kilometres between August 2020 and July 2021. If the government fails to comply with this obligation, the plaintiff seeks the reforestation, as soon as technically possible, of any deforested area that exceeds the annual legal limit.

Political parties and climate change litigation in Brazil

In Brazil, political parties have the right to pursue judicial relief on alleged violations of constitutional rights and human rights directly before the Supreme Court. Since the process of democratisation in the 1980s, political parties have made extensive use of their power to request judicial review of legal and administrative measures established by the legislative and executive branches, either through declaratory or injunctive instruments. On the back of this long history of constitutional litigation, political parties are now turning their focus to the adjudication of climate change.

In June 2020, four opposition political parties filed two climate lawsuits before the Supreme Court. The first case calls on the government to mobilise resources from the Amazon Fund, which was created through donations from Norway and Germany with the aim of curbing deforestation.

The second case seeks to compel the Ministry of the Environment to reactivate the governance structures of the National Fund for Climate Change (Climate Fund) in order to resume disbursement. The Climate Fund was established by federal law in 2009 to finance climate change mitigation and adaptation projects. The fund is replenished in a number of ways, most notably by royalties from oil exploration. During the early months of the Bolsonaro administration, the government agency responsible for the Climate Fund was dissolved, and its steering committee was disbanded, leaving the fund inactive.

In response, the plaintiffs in this second case seek an injunction requiring the fund to prepare an annual plan for the utilisation of its resources and also a declaration of “unconstitutional omission” against the government for its refusal to lend or grant the 300 million reais (nearly 60 million US dollars) currently languishing in its coffers. In September 2020, the Supreme Court convened a two-day public hearing to collect expert views and clarify the facts involved in the case.

In November 2020, these four political parties joined forces with three other political parties and a coalition of NGOs in order to file another lawsuit (Action Against the Violation of a Fundamental Constitutional Right) before the Federal Supreme Court, this time relating to governmental acts and omissions in its execution of the Action Plan for Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon. The plaintiffs also claim that the government has violated fundamental rights of the populations living in the Amazon and throughout Brazil, particularly the rights of indigenous peoples and traditional communities but also those of present and future generations.

Brazil as a future battleground for climate change litigation

Overall, the legal and institutional foundations for more direct climate change litigation in Brazil are solidifying. This is particularly important when we consider that Brazil, whose greenhouse gas emissions are the seventh highest in the world and rising rapidly, looks set to become the next big battleground for climate change litigation.

Future legal action is likely to challenge the failure of federal and state governments to implement measures upholding Brazil’s nationally determined contribution (NDC) to the Paris Agreement, specifically in relation to forestry and changes in land-use. Brazil’s NDC commits to a 37% reduction in emissions by 2025, as well as aiming for a reduction of 43% by 2030. In the document submitted to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Secretariat, Brazil specified that this would be achieved through measures such as an 80% reduction in illegal deforestation, yet today’s annual deforestation rate of 10,000 square kilometres amounts to 250% of the target’s implied limit of roughly 4,000 square kilometres.

Public prosecutors, political parties, and some prominent NGOs are well-placed to add climate change to their current work on strategic litigation relating to environmental and human rights. The creation of the Amazon Taskforce and the growing assertiveness of NGOs and political parties in using climate change arguments to protect environmental and climate governance are key developments. They reflect a steady move towards the consolidation of institutional and legal foundations upon which future climate change litigation will need to be built.

How the courts will decide these cases remains unclear, however. Despite the considerable volume of environmental cases, using litigation to enforce climate change laws is relatively unusual and the positions of the High Court and the Supreme Court on climate-related obligations have yet to be revealed. The High Court has implicitly and indirectly tackled climate change concerns in some cases, as with the use of fire to harvest sugar cane and the clearance of mangrove forests to make space for landfill, but the Court has yet to address climate change in a more substantive manner. One particular issue is that the judiciary has not provided a climate-oriented interpretation of the civil liability regime relating to environmental damages and landowners’ obligations towards protected areas.

Even so, the current wave of cases addressing climate science and climate change laws expands the menu of possibilities for litigants that wish to hold the government – and indeed private actors – accountable for actions and omissions that undermine Brazil’s domestic legislation and international climate change commitments.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting