Professor Duncan Green gives us an insight into Doughnut Economics, and tells us why this popular book has the potential to make life sweeter. This article has been cross-posted (and slightly updated) from From Poverty to Power.

Author, Kate Raworth, will be talking about her book, Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, on Thursday 23rd November at the LSE. Click here for more information.

My Exfam colleague Kate Raworth’s book Doughnut Economics is launched today launched in April, and I think it’s going to be it’s big. Not sure just how big, or whether I agree with George Monbiot’s superbly OTT plug comparing it to Keynes’s General Theory. It’s really hard to tell, as a non-economist, just how paradigm-changing it will be, but I loved it, and I want everyone to read it.

Down to business – what does it say? The subtitle, ‘Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist’, sets out the intention: the book identifies 7 major flaws in traditional economic thinking, and a chapter on each on how to fix them. The starting point is drawings – working with Kate was fun, because whereas I think almost entirely in words, she has a highly visual imagination – she was always messing around with mind maps and doodles. And she’s onto something, because it’s the diagrams that act as visual frames, shaping the way we understand the world and absorb/reject new ideas and fresh evidence. Think of the way every economist you know starts drawing supply and demand curves at the slightest encouragement.

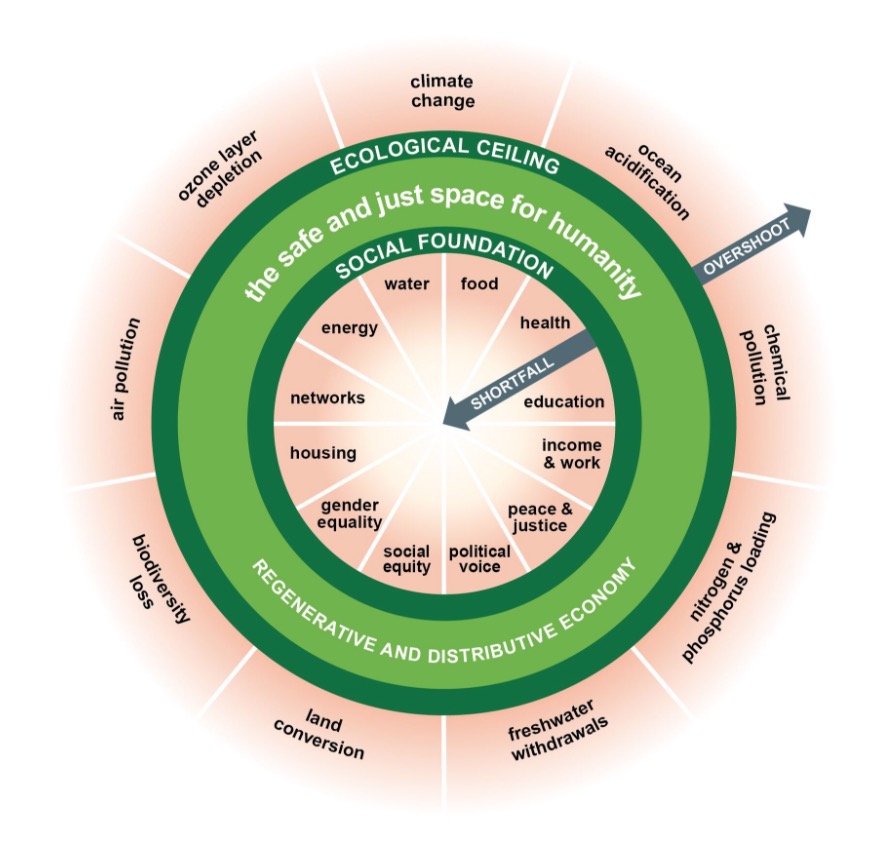

Her main target is GDP (the standard measure of national economic output), and its assumptions – an open systems approach to economics that ignores planetary boundaries as it promotes economic growth. Her breakthrough moment while at Oxfam was coming up with ‘the doughnut’ – two concentric rings representing the planetary ceiling and minimum standards for all human beings. The ‘safe and just space’ between the two rings is where our species needs to be if it wants to make poverty history without destroying the planet.

When Kate came up with the doughnut in a highly influential 2012 paper for Oxfam, my non-visual mind failed to grasp its full value. After all, wasn’t this just a restatement of the idea of sustainable development? But it went viral, especially at the UN, because it allowed activists and policy makers to visualize both the threats and how they were trying to overcome them.

The other 6 main chapters cover:

- ‘See the big picture’: seeing the economy as ‘embedded’ in wider social and environmental systems

- A critique of individualist ‘rational economic man’ that redraws the object of economics as social, adaptable humans

- Moving from equilibrium economics to complex adaptive systems

- Forget Kuznets: growth won’t lead to falling inequality – the economy must be ‘distributive by design’

- Forget Kuznets II: growth won’t clean up the environmental damage it helps cause – the economy needs to be ‘regenerative by design’

- Where does growth fit? Need to move from the current financial, political and social addiction to growth, to allowing GDP to adjust up, down, or oscillate, as the economy transforms

These bald summaries do no justice to the writing (Kate writes beautifully – leaving Oxfam seems to have liberated her), or the content (see last week’s posted extracts for a taste). There’s erudition, in the summary and critique of the main economic ideas, accompanied by smart biographical asides. Here’s a lovely example on the ‘care economy’:

‘in extolling the power of the market, Adam Smith forgot to mention the benevolence of his mother, Margaret Douglas, who raised her boy alone from birth. Smith never married and at the age of 43, as he began to write The Wealth of Nations, he moved back in with his cherished old mum, from whom he could expect his dinner every day. But her role never got a mention in his economic theory.’

That comes along with a comprehensive introduction to new economics theory and practice – a compendium of hundreds and thousands of innovators, activists and thinkers trying to incubate new thinking on money, financial systems, tax. Pretty much everything is ripe for redesign, with an urgency created by the tick tock of climate change. ‘Ours is the first generation to properly understand the damage we have been doing to our planetary household, and probably the last generation with the chance to do something about it’.

The chapter I must enjoyed was when she comes back to growth and discusses the bicycle problem (although she never calls it that). What if growth is like a bicycle – if you stop moving forward, you fall off? If politics, society and the structure of capitalism depends on growth (for example by requiring a return on investment, or through the nature of market competition), how can they wean themselves off it and survive? She wrestles with the arguments, coming up with this memorable summary of the two camps:

‘The keep-on-flying passengers: economic growth is necessary – and so it must be possible

The prepare-for-landing passengers: economic growth is no longer possible – and so it cannot be necessary’.

Although she claims to be agnostic, her sympathies clearly lie with the second camp, and the chapter sets out some fascinating ideas – rethinking the nature of money, reforming finance, changing the nature of taxation, new metrics – for how society needs to ‘prepare for landing’. That seems like a thoroughly original and brilliant way to get past the insane optimism of the exponentionalists, and the sloppy oppositionalism of the degrowthers.

Wonderful, but what influence will the book have? Because in some ways Doughnut Economics is an example (albeit a particularly brilliant one) of what I call IIRTW (‘If I Ruled the World’) thinking. There’s a cursory nod to the nature of power, but the implicit theory of change seems to be to invoke a sort of progressive/environmentalist version of Silicon Valley – a movement of smart, dedicated people building a New Jerusalem. Their brilliance will identify the win-win solutions, while some ill defined political upsurge will overcome the blockers. Together they will save the world.

What’s missing is a decent power analysis and discussion of how the ideas interact with politics (beyond broad social movement activism): not just the power of bad guys, but the workings of democracy. When I discussed this issue with Tim Jackson, another environmental economist guru, he ended up accepting that autocratic systems were probably the most likely to implement his ideas.

But great ideas, and brilliant framing, still make change – and this book is a classic combination of both. If only 10% of the ideas get implemented, the world will be a much better place. And I’m always happy to help if Kate wants to write a follow up – Doughnut Politics anyone?

Here’s Kate summarizing her message on Open Democracy. And in keeping with her commitment to visuals, check out these brilliant animations of the book’s main ideas. Here’s the first, setting out her stall on GDP.

Duncan Green is Professor in Practice in the Department of International Development and Senior Strategic Adviser for Oxfam UK.

This article was first posted in From Poverty to Power.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the International Development LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.