Earlier this month, the verdict of the ‘wolf pack’ case sparked the #MeToo movement to spread across Spain. Both in the streets and on social media platforms, the court decision was met with uproar. According to the supporters of the campaign, the judges were biased, and their decision was overly lenient towards the perpetrators and rather unfair to the victim. This event brought forward the institutionalisation of patriarchal attitudes in the justice system and the systematic discrimination against victims of gender-based violence (GBV). Even if several months later, the movement which started in Hollywood last October, reached Spain, too.

Unlike Spain, Greece remains largely silent on that front. Why is that? Some would say that Greece has more urgent concerns on the table at the moment, such as materialising the structural reforms tied to the memoranda or accommodating a continuous influx of asylum seekers. That is true. However, there is a common denominator permeating most of Greece’s, surfaced or unsurfaced, crises: the gap between policy and practice. In the case of GBV, there is indeed a modern and progressive legal framework on paper, but, in practice, the laws are not usually enforced as they should be. Partly, of course, this has to do with material factors: low levels of institutional capacity, poorly equipped material structures and lack of control mechanisms.

Apart from the tangible side of things, however, there is also an issue of mentality and education, or the lack thereof. According to field research I conducted in Athens and Crete in the summer of 2011, institutionally imbedded patriarchal notions are obviously a major impediment to the implementation of GBV-related policies.

“There are many policemen who would say to a [battered] woman who came from a nearby village, for instance, ‘Oh, come on now Maria, George loves you. We know him. He’s a nice guy. You should go home, and you guys will figure things out. He won’t do it again. We’ll tell him not to do it again, too’.”

“We had an incident of a woman who came to us shackled. Her husband had shackled both her arms and legs…And the chief policeman called that guy to prevent him from getting arrested! He said ‘Manoli’ for example, ‘your wife is pressing charges, so we have to come and arrest you. Go and hide’!”

“I know cases where the woman says, ‘OK, I don’t care anymore. I’ve had enough. I don’t care if I get stigmatised or if people gossip about me’. And then, her mum doesn’t let her… She might hit her, too. She tells her ‘we’re not going to embarrass ourselves in the neighbourhood!”

(Interviews with social workers, 2011)

As these examples show, there is a significant lack of awareness surrounding the issue of GBV. And, when this lack is prominent among those who are meant to implement the law, in the end, justice itself is being compromised.

To be fair, significant steps have been achieved since 2011 for the protection of GBV victims. Despite the economic limitations, there is now a 24hr helpline, 21 shelters and 39 consulting centres operating across the country, while several sensitisation campaigns have also been run since then. However, there is still a lot more to be done. In rural areas in particular, the hesitation by victims to seek help and trust the authorities remains a persistent problem, mainly due to the fear of judgement by their social environment.

“There are hostels that are empty and others that are super busy, depending on the area. In remote areas, women don’t come forward about this problem. In the islands, for instance. In Athens it is easier to stay anonymous.”

(Interview with GSGE[1] employee, 2017)

As this quotation suggests, society plays an important role in whether victims report incidents or not. Undoubtedly, traditional gender roles and stereotypes are deeply imbedded, not only in institutional norms and practices, but in people’s minds as well. Therefore, awareness needs to be raised not only among professionals, but also among the general public, which is what the #MeToo Movement aims to achieve.

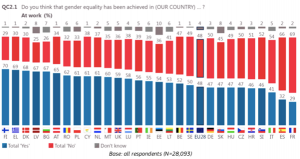

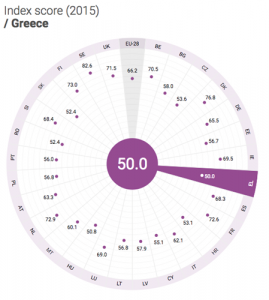

So, why do Greeks appear hesitant to jump onto this movement’s bandwagon? Perhaps, the answer lies in the gap between perception and reality. With regard to the former, official reports show that the Greek public feels very positively about their country’s achievements in the gender equality realm. In fact, Greeks are the second most confident EU citizens in that respect (figure 1). Nonetheless, Greece has the lowest score in the EU when it comes to actual gender equality, counting for a wide variety of aspects, including violence (figure 2). In other words, Greeks are among the Europeans who are the least concerned with gender equality, while simultaneously they are performing the worst. Although this observation does not directly correspond to perceived versus actual GBV levels (which are difficult to measure given the low awareness and reporting rates), it does provide a significant indication. That is to say, it may not be merely that ‘we don’t know’ about GBV issues. Rather, it may be that ‘we don’t know we don’t know’. If so, the Greek society is a bubble that is harder for the #MeToo Movement to burst.

Figure 1

Source: Special Eurobarometer 449, 2016

Figure 2

Source: European Institute for Gender Equality, 2017 Report

[1] General Secretariat for Gender Equality, Greece

Katerina Glyniadaki is PhD Candidate at the European Institute, LSE and Managing Editor of GreeSE Paper Series.