How have businesses been affected by the pandemic in Slovakia? The impact is very different from that of the Global Financial Crisis, writes Martin Pažický (Comenius University). Business registrations have declined, which may lower productivity, and medium-sized enterprises suffered most.

The pandemic hit Slovakia particularly hard in autumn 2020. The government responded with a series of restrictions in an effort to slow down the spread of the virus. They have taken an economic toll in the form of a drop in output and employment. Various support schemes, including tax deferrals, wage subsidies, cost allowances and loan guarantees, aimed to protect jobs and help businesses stay afloat. Over time, the scars on businesses are becoming more and more obvious.

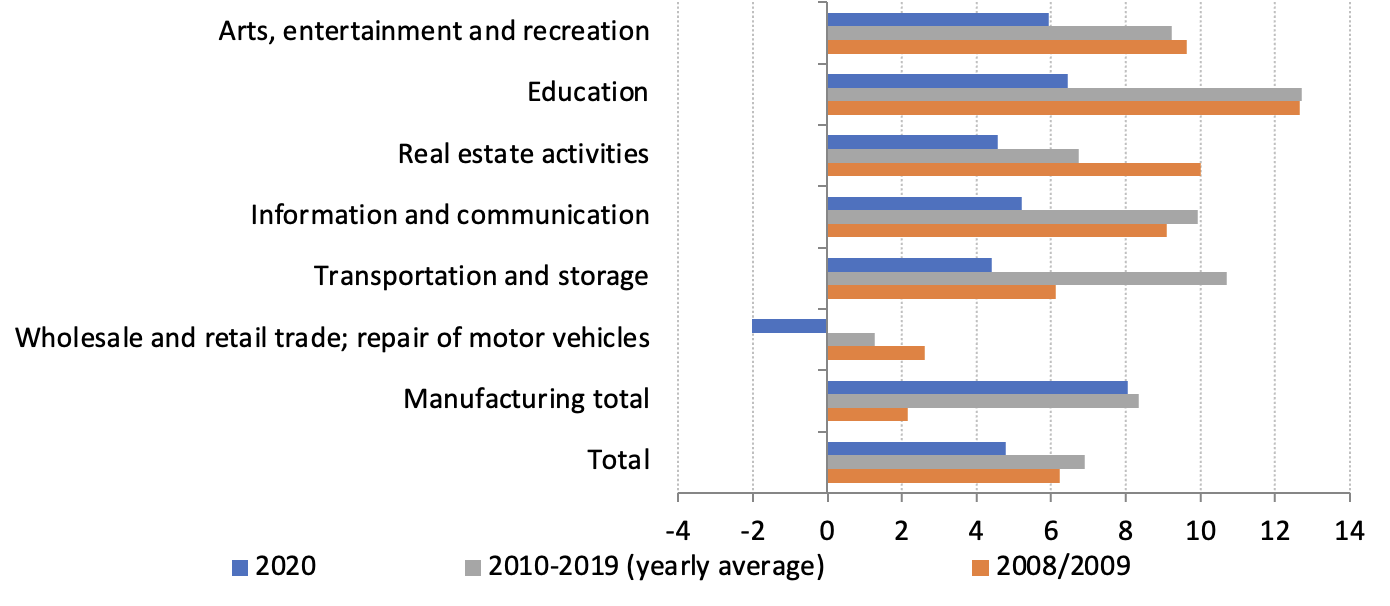

The growth in the number of state-registered businesses operating in Slovakia slowed down in 2020 in all sectors compared to the pre-COVID period. The only sector where the number actually declined is wholesale and retail trade (Figure 1). This is different from the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) in 2008-09, when the growth in the number of enterprises was slower than in the following decade of solid economic growth. During the pandemic, the slowdown in business dynamics was more pronounced than during the GFC. A positive exception is manufacturing, where the number of enterprises grew at a comparable pace with previous years. For a small, export-oriented country with a high share of industry (especially car manufacturing) like Slovakia, maintaining the number of industrially-oriented enterprises is encouraging. The data on the number of businesses is in line with signals from other sources, such as revenue or production, where it appears that industry has already recovered. More contact-sensitive services have suffered much greater losses.

Figure 1: Change in the number of enterprises in Slovakia – financial crisis vs COVID (year-on-year, %)

Source: Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic (SOSR)

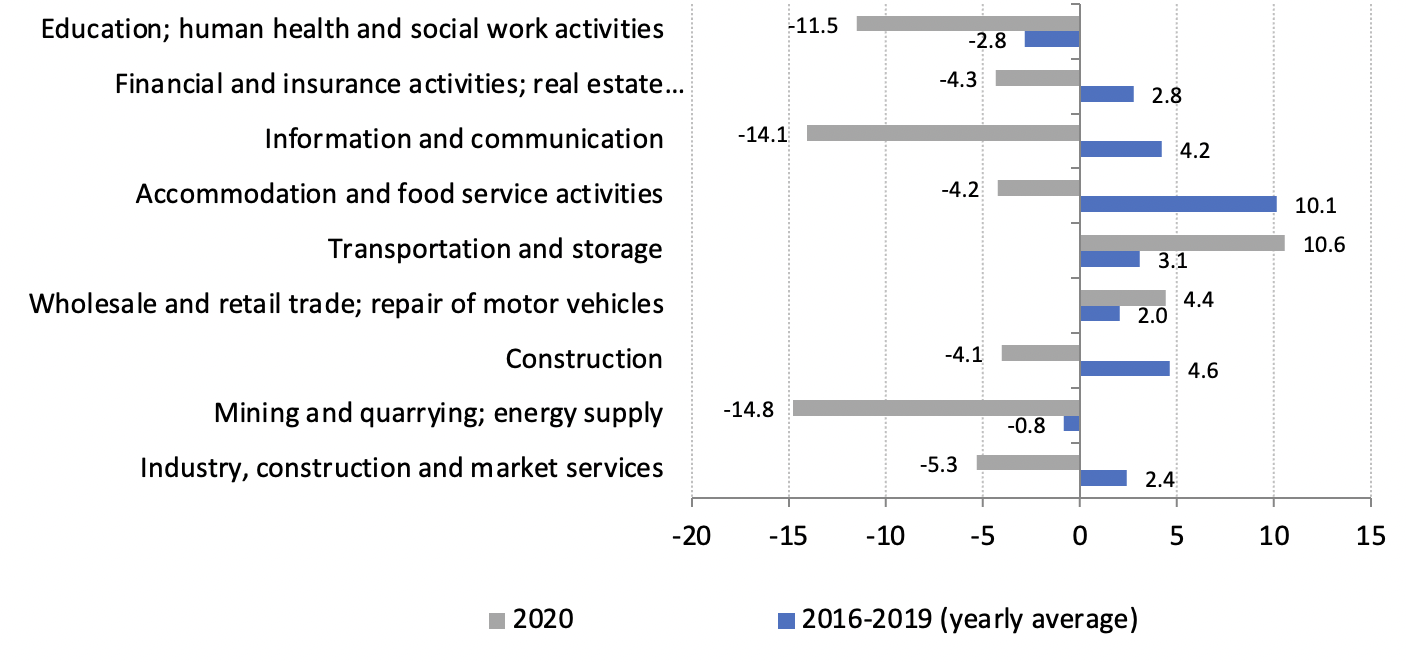

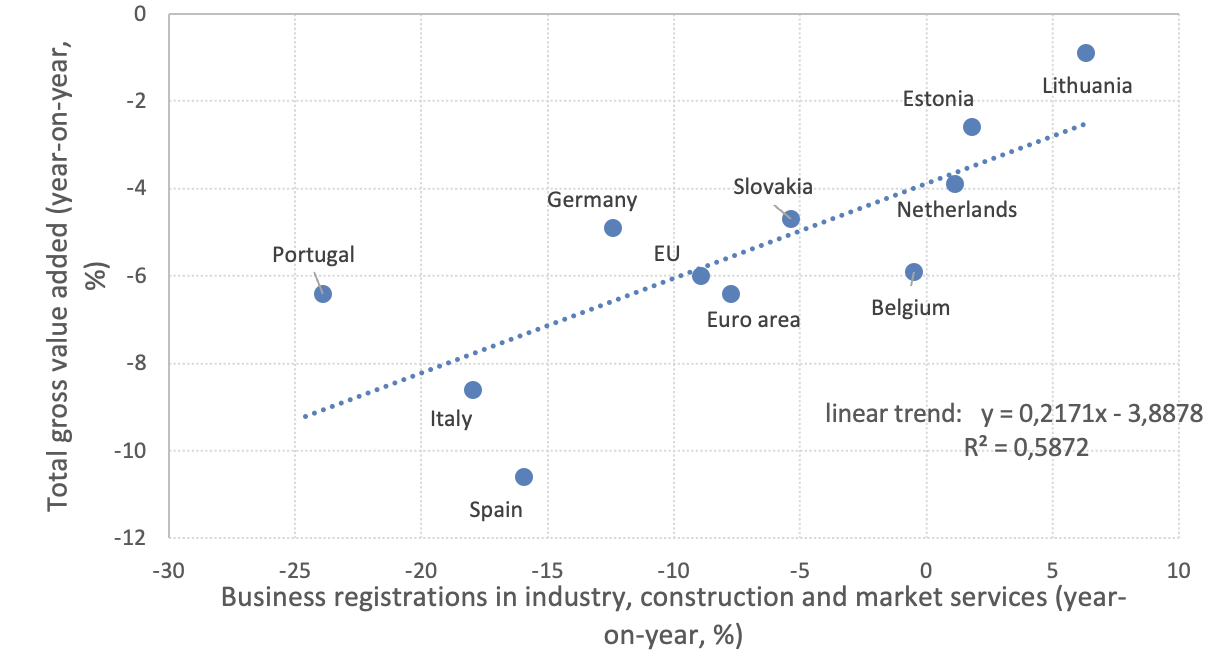

But data on the number of businesses does not provide enough information about future productivity, which can be affected by two channels: enterprise births and deaths. Enterprise birth in Slovakia is relatively easy: it takes 21.5 days on average. Enterprise death is more complicated to record as it can take between three months (in cases of bankruptcy) to several years (liquidation). In most sectors, business registrations fell compared to the pre-pandemic period. While a decline in some sectors such as education and hospitality was to be expected, the sharp fall in information and communication business registrations is worrying, as it may mean lost opportunities for innovation and productivity growth (Figure 2). In 2020, a relatively strong relationship can be observed between business registrations and added value across selected European countries (Figure 3). Longer-lasting weak interest in starting new businesses can not only slow down economic growth, but also cut productivity in some sectors. The only sectors where business registrations grew are transportation and storage and wholesale and retail trade, similar to the Netherlands, where new business entries have slowed down in all sectors except wholesale and retail trade.

Figure 2: Business registrations in Slovakia by economic activity (year-on-year, %)

Source: Eurostat

Figure 3: The relationship between business registrations and added value in Europe in 2020 (%)

Source: Eurostat

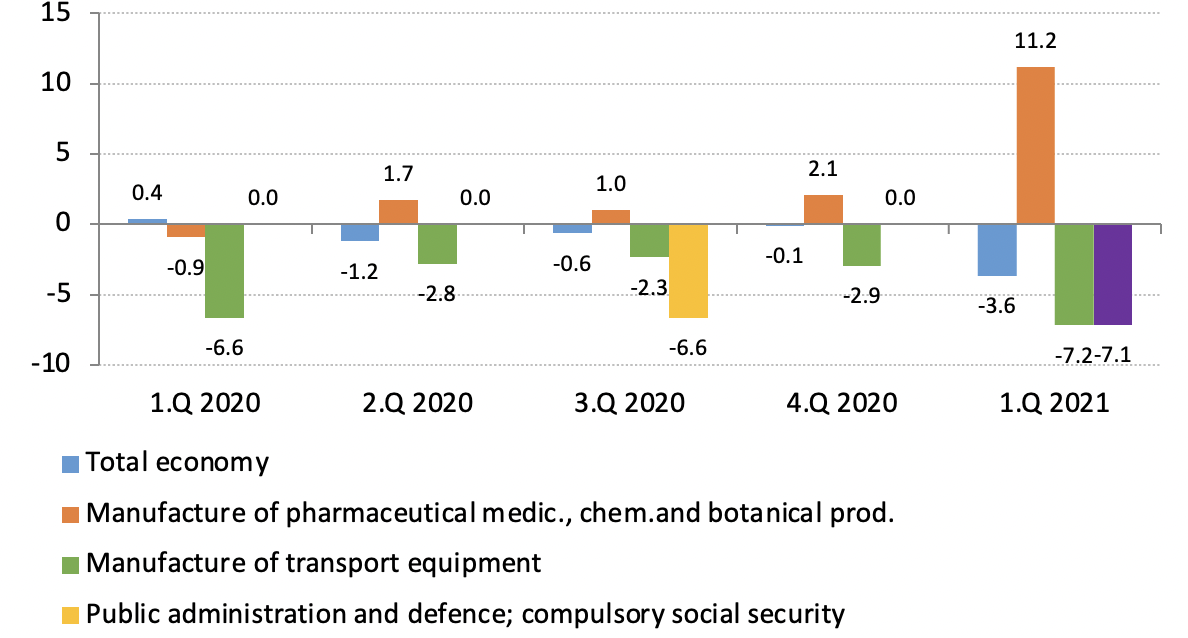

The quarterly view reveals that in Slovakia, cumulatively from the 2nd quarter of 2020 to the 1st quarter of 2021, 35 out of 38 sectors of the economy had fewer businesses. The manufacture of transport equipment sector fell the most, which largely reflects a shortage of components and chips in the first half of 2021. Overall, the number of enterprises in the economy has decreased cumulatively by 5.5 % since the pandemic. Pharmaceuticals and medical products manufacturing, on the other hand, rose.

Business dynamics were uneven across quarters during the pandemic. The most significant drop in the number of companies was not until the first quarter of 2021 (Figure 4), which may reflect the postponement of bankruptcies to the following year for behavioural reasons, but also support measures, which in many cases helped delay bankruptcy. The impact of the crisis on company size was also heterogeneous. During the pandemic, the number of medium-sized businesses in Slovakia decreased the most. However, the number of small businesses with less than 50 employees has increased slightly, possibly due to support measures. The effect is very uneven across sectors.

Figure 4: Impact of the pandemic on the number of enterprises over time (quarter-on-quarter, %)

Source: SOSR. Note: The figure shows differential growth between the crisis and pre-crisis periods, where the growth in each quarter is compared to the average growth in the respective quarter for the previous four years (i.e., from Q1 2016).

The priority now is to avoid re-importing the virus. Arrivals should be required to show a negative PCR test or a vaccination certificate before entering the country. It is also crucial to create capacity to trace infected people and their contacts, who must quarantine themselves at home. As the Delta variant is likely to spread in the autumn, it is appropriate to consider a further extension of the furlough scheme and support for the self-employed, which was due to end at the end of June 2021, when it will be replaced by the rules of the “COVID Automat”.

After the pandemic has subsided, it is essential to adopt measures to revive the economy. Given that Slovakia has the highest corporate tax rate in Central and Eastern Europe, it would be appropriate to reduce this tax from the current 21% to improve the business climate make the country more competitive. Depreciation on investment property can support research and investment and increase business registrations. Education, research and development and ICT would benefit.

In the longer term, the government should support new, innovative regional start-ups. This has the potential not only to improve the productivity of SMEs, but also contribute to the shift to a more sustainable knowledge-based economy, reduce regional disparities and boost employment. Finally, employees should be prepared for new job opportunities, and the training and re-qualification of employees should not be neglected.

This column represents the opinions and calculations of the author. It does not represent the position or opinions of the Ministry of Finance of the Slovak Republic, nor the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.