This post was contributed by Amelia Evans, Co-Founder of MSI Integrity, and Stephen Winstanley, Coordinating Attorney at MSI Integrity.

Over the last two decades, voluntary standard-setting initiatives have proliferated, becoming one of the most popular tools for addressing the human rights impacts of global business activities. These initiatives have accomplished something significant: they have established voluntary human rights standards for every major global industry, from finance to agriculture, technology to clothing. Indeed, over 180 standard-setting initiatives that address social, ethical, or environmental issues have now been mapped.

But despite their proliferation, we still cannot answer a fundamental question: are voluntary initiatives protecting human rights? More fundamentally, why don’t we know whether these initiatives are protecting human rights?

As stakeholders gathered this week for the annual UN Forum on Business and Human Rights to discuss the theme “tracking progress and ensuring coherence”, we offer a roadmap for deepening the conversation so we can begin to answer these questions.

First, we need to link any discussion of “progress” to real evidence of the protection of human rights–or suitable proxies–rather than simple but unhelpful measures, such as the number of companies that join an initiative, or the policy pledges they make when joining. Second, standard-setting initiatives themselves–and thus their company members–should embrace rigorous and independent evaluations that will determine whether progress is being made towards protecting human rights.

What are voluntary standard-setting initiatives?

Standard-setting initiatives go by a number of names, such as industry codes or private regulation. If they involve other stakeholders they may also be multi-stakeholder initiatives.

Regardless of the name, these initiatives establish standards relating to specific industries, geographic regions, or human rights issues. Companies (or sometimes governments) may voluntarily choose to join or create an initiative, but once they join they are expected to comply with that initiative’s standards.

Frequently, initiatives go several steps further, such as by monitoring members for compliance with the standards or, as the UN Guiding Principles encourage, establishing a grievance mechanism. In this way, they are often seen as adopting a quasi-regulatory role by attempting to close a governance gap that results when state actors are unable or unwilling to use their authority to ensure rights are protected and promoted.

Defining progress: What does it mean to be an effective standard-setting initiative?

What is progress? Standard-setting initiatives frequently trumpet the inclusion of new companies, or the expansion to new industries or issues, as markers of success. However, expanding the size or scope of an initiative should not, by itself, be seen as a measure of “progress” from a human rights perspective—an initiative could cover an entire industry, but have made few gains on the ground.

Another commonly misconceived notion of progress is to look solely at the commitments a company makes as a result of joining of an initiative. As Margaret Jungk and the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights have noted, this is important, but we need assurances that companies are meeting those commitments.

The bottom line from a human rights perspective is that an effective initiative ensures the protection (or promotion) of human rights for the rights-holders that the initiative is intended to benefit. Examples of rights-holders could include workers, children, or other affected communities. Measuring “progress”, therefore, requires asking about the rights protection experienced by affected communities and the outcome that results from implementing standards.

Human rights impact assessments are still novel terrain, made more complex when measuring entire systems rather than individual sites, and if done poorly could risk causing more harm than good. However, considerable progress has been made on the wider question of how to conduct human rights impact assessments, with practitioners learning lessons about how involving rights-holders throughout the process is critical and organizations beginning to release methodologies for measuring human rights impacts.

However, measuring human rights impacts or outcomes requires considerable time, resources, and expertise. It may also require key actors to open their doors to external evaluation. In instances when it is not feasible to measure human rights impacts, we encourage actors to use appropriate proxies to examine whether an initiative may protect human rights.

For example, although it may seem, counter-intuitive, if an initiative regularly and transparently reports violations by members it may be a form of positive evidence about the initiative progress. Thus, last month’s decision by Forest Stewardship Council—to investigate and de-certify a rubber company after findings of human rights and environmental abuse—should not be seen as a sign of the initiative failing, but as an encouraging sign of the initiative’s capability to hold member’s accountable for wrongdoing.

Of course, one-off incidents are not enough to demonstrate deep human rights protection and “progress”. But, initiatives that routinely and honestly report levels of compliance with their standards should raise fewer eyebrows than initiatives that only report back glossy and heart-warming stories of output-oriented results.

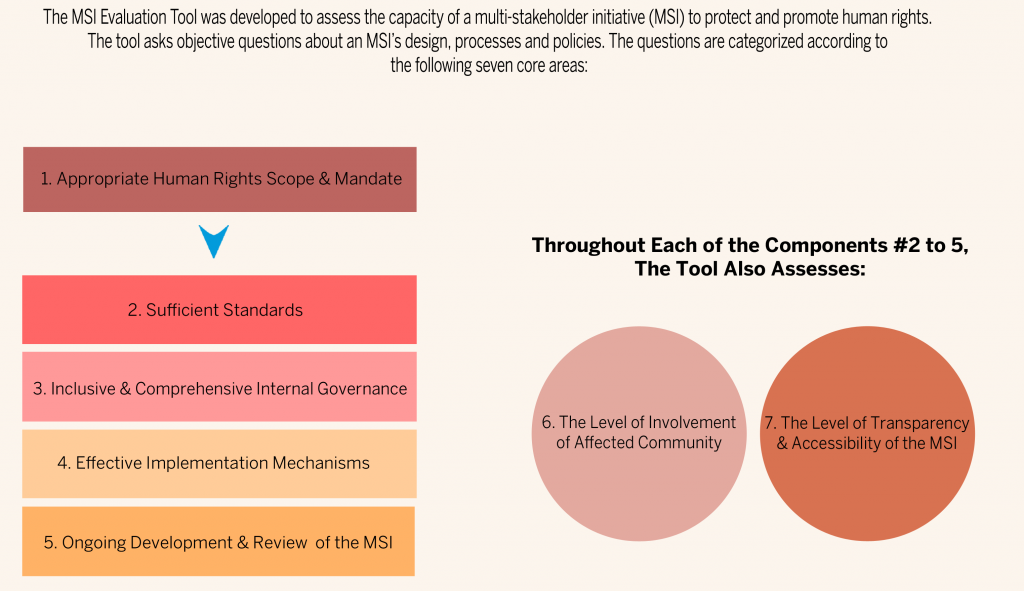

To support actors looking for such measures, MSI Integrity has spent several years developing the MSI Evaluation Tool for evaluating the design of multi-stakeholder initiatives. The underlying premise of the Tool is that a well-designed initiative–for example, one with rigorous monitoring systems, effective grievance mechanisms, and high-levels of involvement of affected communities–is more likely to protect human rights than an initiative that lacks these features, and that examining the design of an initiative can be easier than measuring its outcomes and impacts.

An overview of the core areas evaluated in the Tool, which will be publicly released in the coming months after incorporating feedback from extensive global public consultation, is below:

Why don’t we know if standard-setting initiatives are protecting human rights?

Why don’t we know if standard-setting initiatives are protecting human rights?

Fundamentally, we do not know whether voluntary initiatives are protecting human rights because no culture of critical evaluation about the effectiveness of these initiatives has yet emerged. Much goodwill, energy, and excitement has surrounded the development of standard-setting initiatives. Now it is time to apply that goodwill and energy to understanding whether, or in what conditions, these initiatives can yield “progress” for protecting human rights.

MSI Integrity was founded to foster a culture of critical evaluation and inquiry about the effectiveness of voluntary initiatives for protecting human rights, but we cannot tackle this enormous task alone. We strongly encourage standard-setting initiatives, and their members and funders, to pause and ask important questions about whether they have been effective, and to examine how they have been effective by opening themselves up to rigorous, independent, and transparent evaluations.

It is also important that the business and human rights community agrees upon key qualities for the reliability of any measures, or measurers, of “progress” or “effectiveness”. This means sharing lessons from human rights impacts assessments, ensuring that evaluators have sufficient human rights expertise, an understanding of local contexts, and that they use a credible methodology to reliably measure levels of human rights protection–or use suitable proxies where this is not possible. If we cannot agree on these fundamental criteria for good measurement, we risk being left with inaccurate or incomplete results, or incentivizing the creation of a cottage industry of consultants that are motivated by deploying the most manageable or profitable measurement approaches, rather than those that put human rights at the center.

After all, without knowing how to define and reliably measure “progress”, how can a company understand if it is sufficiently discharging its responsibility to respect human rights by joining an initiative, since we don’t know in the first place whether that initiative is effective? How can we have an informed discourse on the need for a treaty, if we do not begin to explore whether, or when, voluntary initiatives are working? And most fundamentally, how can we track progress or have confidence that human rights are being adequately protected?

Amelia Evans and Stephen Winstanley

Amelia Evans is an international human rights lawyer and has investigated and reported on business and human rights-related issues in a number of countries, most particularly in the Central African and Asia-Pacific regions. She co-founded MSI Integrity in 2012, and was previously the Global Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Law School and a clinical supervisor at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic. Stephen Winstanley is an international human rights lawyer and currently serves as Coordinating Attorney at MSI Integrity. He has previously worked on business and human rights issues as a Law and Policy Fellow with the International Corporate Accountability Roundtable, and a Research Associate with Partnership Africa Canada.

Amelia Evans is an international human rights lawyer and has investigated and reported on business and human rights-related issues in a number of countries, most particularly in the Central African and Asia-Pacific regions. She co-founded MSI Integrity in 2012, and was previously the Global Human Rights Fellow at Harvard Law School and a clinical supervisor at Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic. Stephen Winstanley is an international human rights lawyer and currently serves as Coordinating Attorney at MSI Integrity. He has previously worked on business and human rights issues as a Law and Policy Fellow with the International Corporate Accountability Roundtable, and a Research Associate with Partnership Africa Canada.