Through social activism Nigerian Pentecostals in London are carving out a space in society and making a claim for public recognition says Simon Coleman.

Our Pentecostalism in Britain series is in collaboration with LSE’s Religion and the Public Sphere blog.

Migration is probably always a combination of opportunity and threat—for both migrants and members of host societies. Things aren’t made much easier when you come from a country often associated with fraud, promote a religion that is often mocked, and are still seeking legal recognition of your right to remain in your new country. That is the situation that has faced many Nigerian Pentecostals over the past few decades as they have come to Britain not only to study but also to stay.

As Joe Aldred’s recent piece has noted, Nigerian born-again believers’ apparent success in gaining a religious profile in London and elsewhere has resulted in what some have called the ‘nigerianisation’ of British Christianity, though as Aldred also states we still need to assess the long-term effects of such activity. Here I explore another dimension of this wave of migration: its relationship to social activism and civic recognition.

I take the title ‘Virtuous Citizens’ from the anthropologist Mattia Fumanti’s work on Ghanaian Methodist migrants to London (and Mattia, in turn, got it from Aristotle). Mattia talks of believers’ performances of “virtuous citizenship,” through which they can claim a space in a suspicious post-colonial context via their civic contributions: whatever its legal status, such performed citizenship has a moral force that makes a claim for public recognition.

I recognise these performances from my own fieldwork within the Redeemed Christian Church of God in London. Founded in Christian-dominated south-western Nigeria in 1952, the RCCG went from strength to strength in the 1980s through presenting itself as an alternative social formation to corrupt government, promoting Nigeria’s true destiny as a Christian nation. While the RCCG message of order and aspiration has resonated in parts of Nigeria, it has also played a powerful role in the lives of members who have migrated to Europe and North America, and sought to live respectable lives in their new homes. Stephen Hunt has recently stated that the RCCG has over 400 congregations in Britain ‘planted’ by ‘mother churches,’ with congregations mostly based in urban contexts and containing West Africans. Many of such congregations have sought not merely to be the recipients of social benefits from others, but also to engage in social activism. In doing so, they have engaged with seats of political and civic power in ways that have indicated significant forms of ‘give’ as well as ‘take.’

An example from a few years ago has distinctly contemporary resonances. In the spring of 2008 a distinguished visitor came to the ‘Novo Centre,’ a drop-in community group for young people located in the Grahame Park Housing Estate in Barnet, North London, and run by the RCCG congregation Jesus House. Looking a little out of place in his smart suit, conservative MP Boris Johnson praised the work of the Centre, referring to it as an example of the faith-based sector that was making a difference in people’s lives.

In one sense, this was an entirely routine visit by a politician, one of a long list of places to flit into and out of that day. But Boris Johnson at the time was in the middle of an ultimately successful campaign to become the next London Mayor. His opponent Ken Livingstone did not visit the Novo Centre but he had attended a large RCCG ‘Festival of Life’ service in London the previous year, despite his well-known credentials as ‘Red Ken’–proud socialist and life-long atheist. For both of these men, the RCCG represented both votes and visibility, and crucially a respectable context in which to be seen, despite the relatively secular tenor of British political discourse.

For Jesus House, meanwhile, the housing estate and community group represented a microcosm of its vision for London. Grahame Park provided a place where boundaries between Pentecostal Christianity and diverse residents, between the ethnic enclave of the ‘black church community’ and the wider public, could be overcome through the respectable institution of a community center. What may have ultimately been at stake here was suggested to me by a young congregation member whom I met in the bookstore of Jesus House, who told me that he and others hoped Jesus House would one day take advantage of the regeneration of the area to become the local parish church—converting the globally-oriented RCCG model of a parish as Pentecostal mission into an Anglican model of the parish as focal point for the community as a whole.

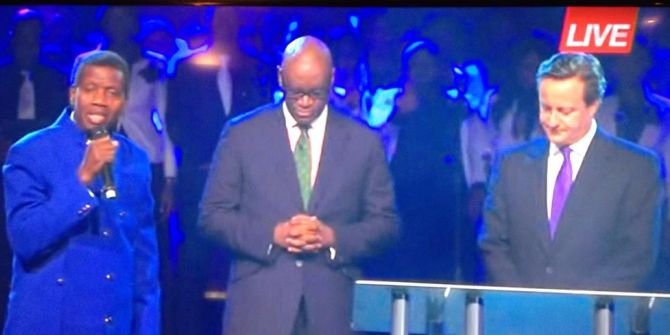

So Boris Johnson was not just gaining access to a given potential constituency of support, he was also permitting that community to depict and deploy him in particular ways. As Mayor of London, he visited Jesus House again on the 9 December 2009 for a Community Carol Service. And a quite astonishing number of other representatives of the great and the good have very publicly passed through the RCCG in recent years. These include Prince Charles and his wife Camilla on the Prince’s 59th birthday in 2007, while a year later Pastor Agu was welcoming Desmond Tutu as guest speaker at a conference celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Tearfund Christian Charity. And to bring the list up to date, in 2015—just before the latest general election—the Festival of Life hosted British Prime Minister David Cameron.

Britain is a place where Prime Minister Tony Blair had notoriously and emphatically been instructed by his political adviser Alastair Campbell that “We don’t do God.” But well-organised groups such as the RCCG indicate that there are nonetheless many ways to “do God” in the civic realm.

Read other articles in the series

Simon Coleman is Chancellor Jackman Professor at the Department for the Study of Religion, University of Toronto; co-editor of the journal Religion and Society: Advances in Research; and President-Elect of the Society for the Anthropology of Religion, American Anthropological Association.

The views expressed in this post are those of the author and in no way reflect those of the Africa at LSE blog or the London School of Economics and Political Science.